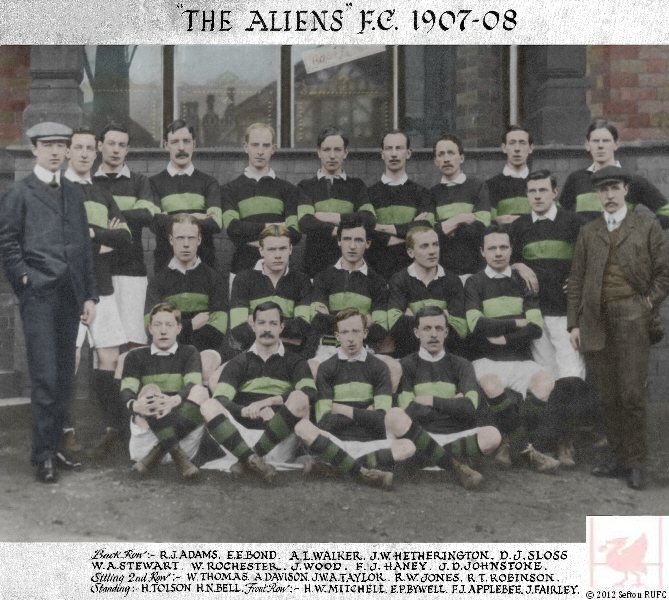

An Alien at War

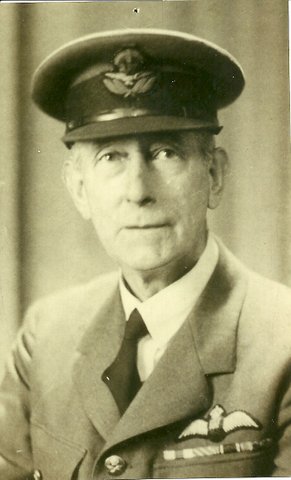

Sqn/Ldr Frederick Joseph Haney

Written and researched by David Bohl, with the kind help and documents supplied by Dr Colm Hickey, Director of Education at John Paul 2 Foundation 4 Sport, and World War 1 historians world wide.

Born in Widnes, 1886 Frederick Joseph Haney trained as a teacher at St. Mary's College, Hammersmith from 1903-05 and taught in Liverpool at Our Lady Mount Carmel RC School. He joined The Alien5 Rugby Union Club based at Clubmoor.

He lived at Lugsdale Road, Peelhouse Lane and Pex Hill before his marriage.

(Colours were black with an emerald hoop)

ALIENS VANQUISH ASHFORD HOUSE.

At Clubmoor the Aliens atoned for the reverse at Preston by a meritorious victory over Ashford House by 17 points to 14. Their forwards again played a storming game. The Alien5 started short of two men, but as soon as they reached full strength Haney's hustle put them ahead. Croxford kicked past Fergusson, and Haney scored, despite Brinson's effort to touch down. Trist failed to convert. This reverse put the House on the qui vive, and a faulty Alien throw in led to a scrimmage before their sticks, when Harris, slipping the scrum, drew level. Vivyan had hard luck with the kick, but afterwards made amends with a brilliant solo try.

Thus the Aliens changed sides a try in arrears. Immediately after the resumption Taylor put the Aliens on an equal footing, while they drew ahead with probably the finest try scored on that ground. Ellis was given possession from the scrum: Crawford accepting an accurate transfer from Thomas, ran clean through the House lines. Bishop converted cooly. Haney and Jones augmented the Aliens' lead, the latter player catching the House napping over a line-out. Vivyan paved the way with a splendid run for a try by Lees. Haney making a blunder which a game tackle by Madoc-Jones was just too late to repair. Vivyan inflated the points, but just failed to improve on Willacy's effort.

Liverpool Daily Post 17/2/1913

|

|

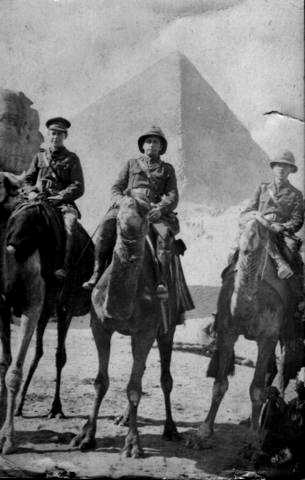

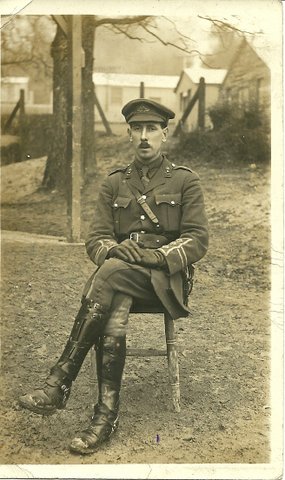

| Royal Artillery - Dec 1915 standing |

1915

in

middle

|

|

|

|

On

right

|

1916 - Probably after Gallipoli evacuation |

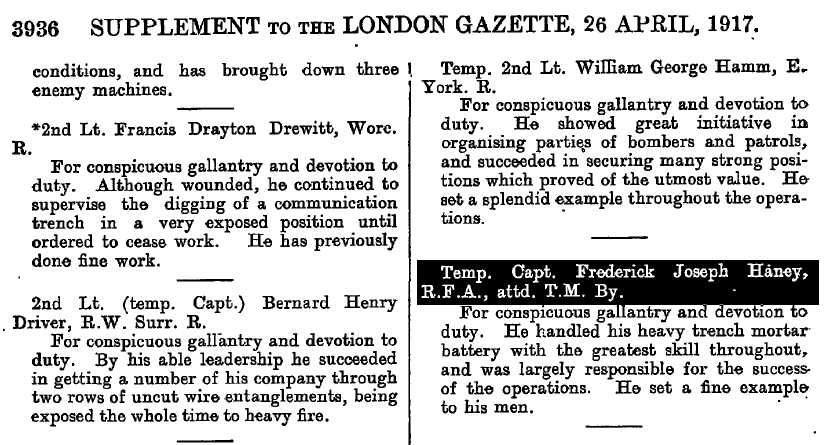

Military Cross Citation 1917

[The longlongtrail.co.uk]

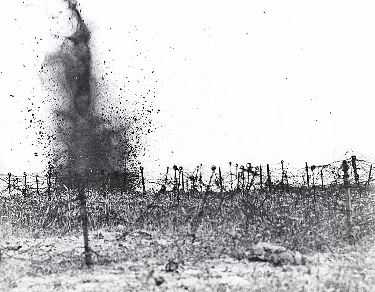

Postcard illustration of a crew loading a

heavy trench mortar. Judging

by the lack of cover and the other soldiers standing around, this is a

posed photograph at a training location.

This section of the site is dedicated to the memory of the officers and men who served the Trench Mortars. Often the focus of infantry grumbling - for a front-line trench mortar was certain to draw enemy fire - the TM Batteries played an important part in gaining the ascendancy in both attack and defence.

Formation and development

In 1914, no organisation existed for trench mortars as the weapons simply did not exist in the British army. Along with the early and faltering development of the weapons, the organisation into batteries was rather haphazard and was left to local command. The infantry, artillery and engineers were all involved from time to time. By December 1915, high command ordered that light mortar units would be manned by the infantry and the medium/heavy units by the Royal Field Artillery. In March 1916, the medium trench mortar batteries formally came under the command of Divisional artillery, while the light Stokes batteries left battalion-level control and came under brigade command. At this time, each Division was given a Divisional Trench Mortar officer, the batteries were numbered, and a badge was introduced to identify mortar personnel.

Armaments

In 1914, the Army was not equipped with trench mortars. The German Army had three types of Minenwerfer, although perhaps only as few as 160 in all. These weapons soon became a dreadful hazard for the scratch trenches in Flanders, the heavy weapon in particular firing a large canister bomb that could destroy many yards of trench. In response, the British authorities decided not to copy the German design on the basis of their inherently unsafe ammunition. Twelve experimental 3.7-inch mortars, with 545 rounds of ammunition, arrived in France in December 1914. They proved to be inaccurate, with a tendency to premature explosion. Forty ancient Coehorn mortars, firing spherical ammunition using black powder charges, were obtained from the French,and were actually fired at the battles at Neuve Chapelle and Aubers Ridge. They were nicknamed Toby mortars, after the officer whose initiative led to their acquisition. In desperation for a short-range artillery weapon, the infantry and engineering workshops improvised, making a variety of weapons, many more dangerous to the firer than to the target. Other devices built to achieve the same effect included catapults. During the first part of 1915, trench mortar production was pitifully small: 75 supplied in the first three months, then 225 in the second. However, the main bottleneck was in providing ammunition: only 8,816 rounds in the first Quarter, and 42,753 in the second. Various models including 1.57-inch, 2-inch, and 4-inch had joined the 3.7-inch in the poor fare with which the Army was supplied.

The breakthrough came in mid 1915, with the acceptance of the 3-inch Stokes mortar. This had been invented in January 1915 by Wilfred Stokes: a design of brilliant simplicity, which became standard issue in the Army for several decades. (200 4-inch Stokes projectors were also made, for gas-filled ammunition. 27 of these fired smoke mortars in the opening barrage at Loos in September 1915). The first production order for 1,000 weapons was issued in August, and 304 were issued in the final Quarter of 1915, of which 200 went to training schools. The Stokes mortar could be operated by skilled crews to have a very high rate of fire, with a number of rounds - perhaps up to nine - in flight at any one time.

By the time of the Battle of Loos in September 1915, the mortars had been arranged into 61 four-gun batteries. GHQ proposed to provide each Division with 6 light batteries, 2 medium and 1 heavy; but this had not been achieved even by the opening of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. By May 1916 it was decided to standardise on three types: the 3-inch Stokes ('light'), the 2-inch Medium (superceded in 1917 by the 6-inch Newton Mortar), and the 9.45-inch Heavy. The latter became available towards the end of 1916, after failed experiments in the summer. The army also called these 'Flying Pigs'.

By 1918 each Division had 24 Stokes and 12 Medium mortars, and a few 9.45-inch Heavy weapons.

Trench mortar tactics

Trench mortars were used in a variety of defensive and offensive roles, from the suppression of an enemy machine-gun, sniper post or other local feature, to the coordinated firing of barrages. Larger mortars were sometimes used for cutting barbed wire, especially where field artillery could not be used, either because of the danger of hitting British troops or where the effect of the fire could not be observed. Experience on the Somme revealed that use of Stokes mortars in an offensive close-support role had been limited by the reluctance of some commanders to sacrifice rifle strength to provide parties required to carry the ammunition which the weapons so quickly consumed.

Trench mortar units

By March 1916, most Divisions had three Medium Batteries, designated X, Y and Z. For example, in the 24th Division they would be X.24,Y.24 and Z.24. There was also the Heavy Battery, designated V, such as V.24. The light Stokes batteries under each Brigade took their number from the Brigade, so for example 123rd Brigade in the 41st Division included 123rd TM Battery from June 1916. Z Battery was in most cases broken up in February 1918, with personnel redeployed to the other batteries.

The destructive effect of a heavy trench mortar round.

(Photo and narrative from The Long, Long Trail www.longlongtrail.co.uk/)

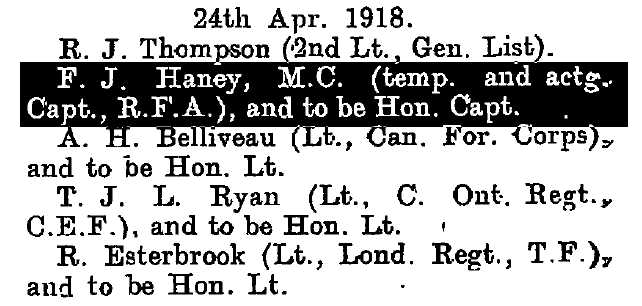

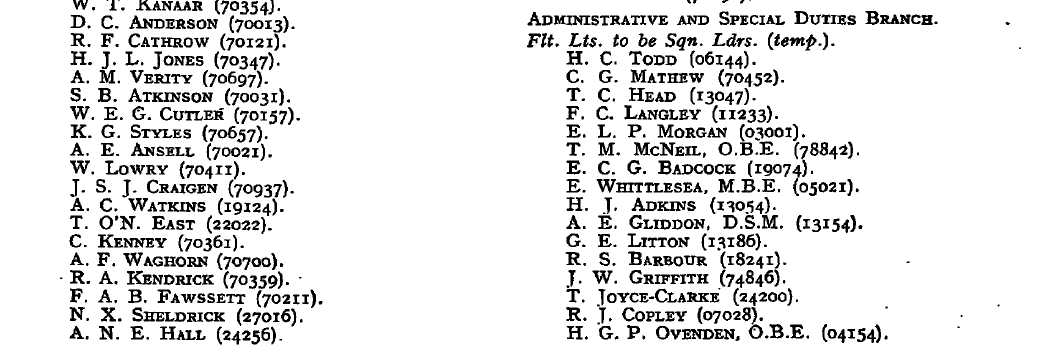

Promotion to Hon. Captain Royal Field Artillery 1918

Transfer to the RAF 1918

|

|

|

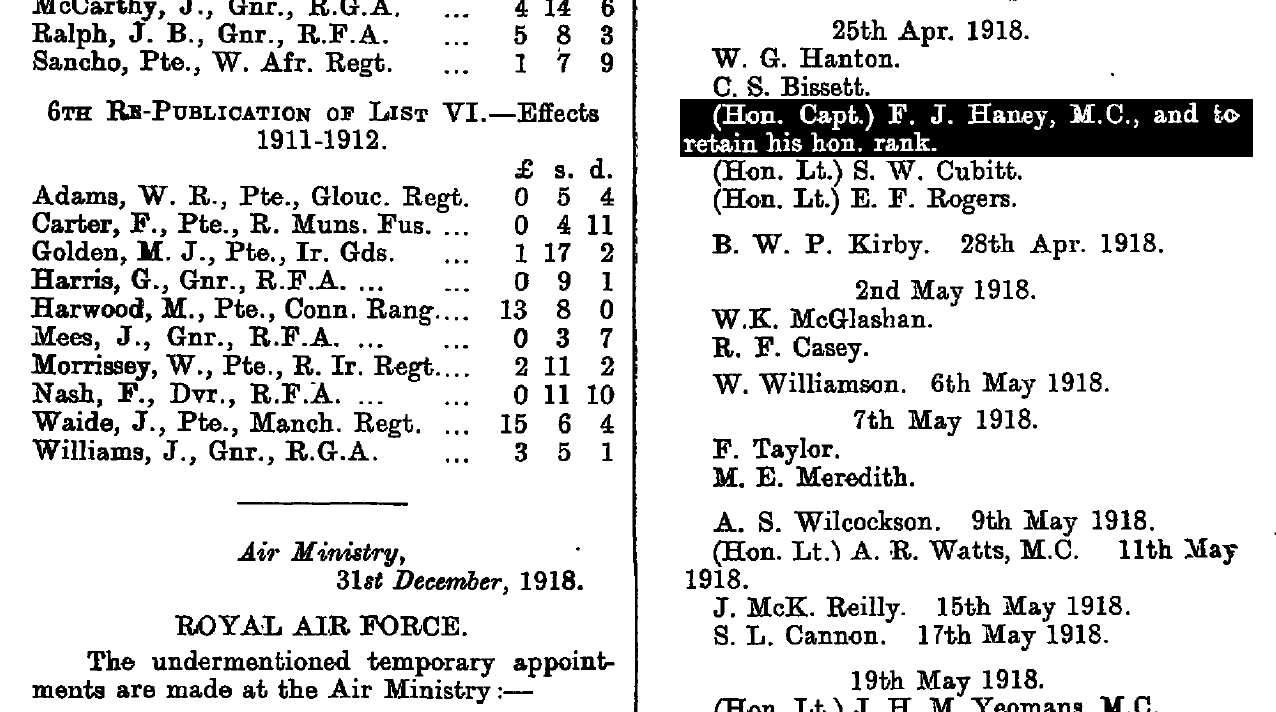

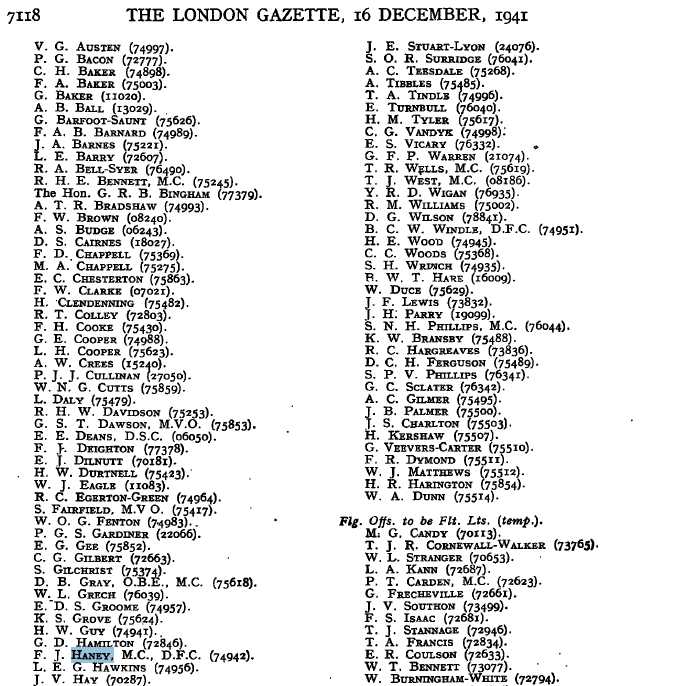

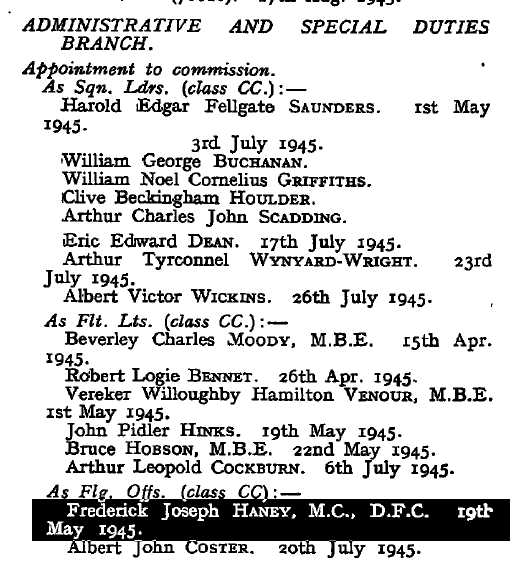

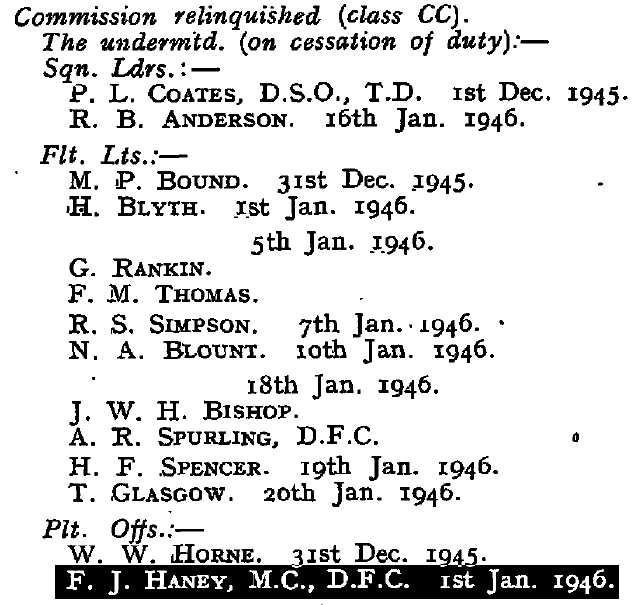

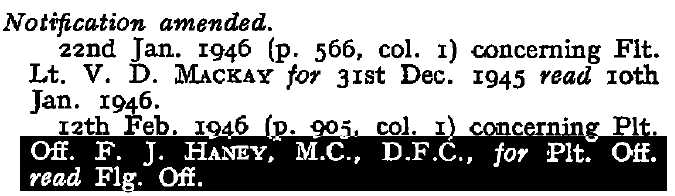

Awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross 1919 (Also listed on Jan 1st in London Gazette)

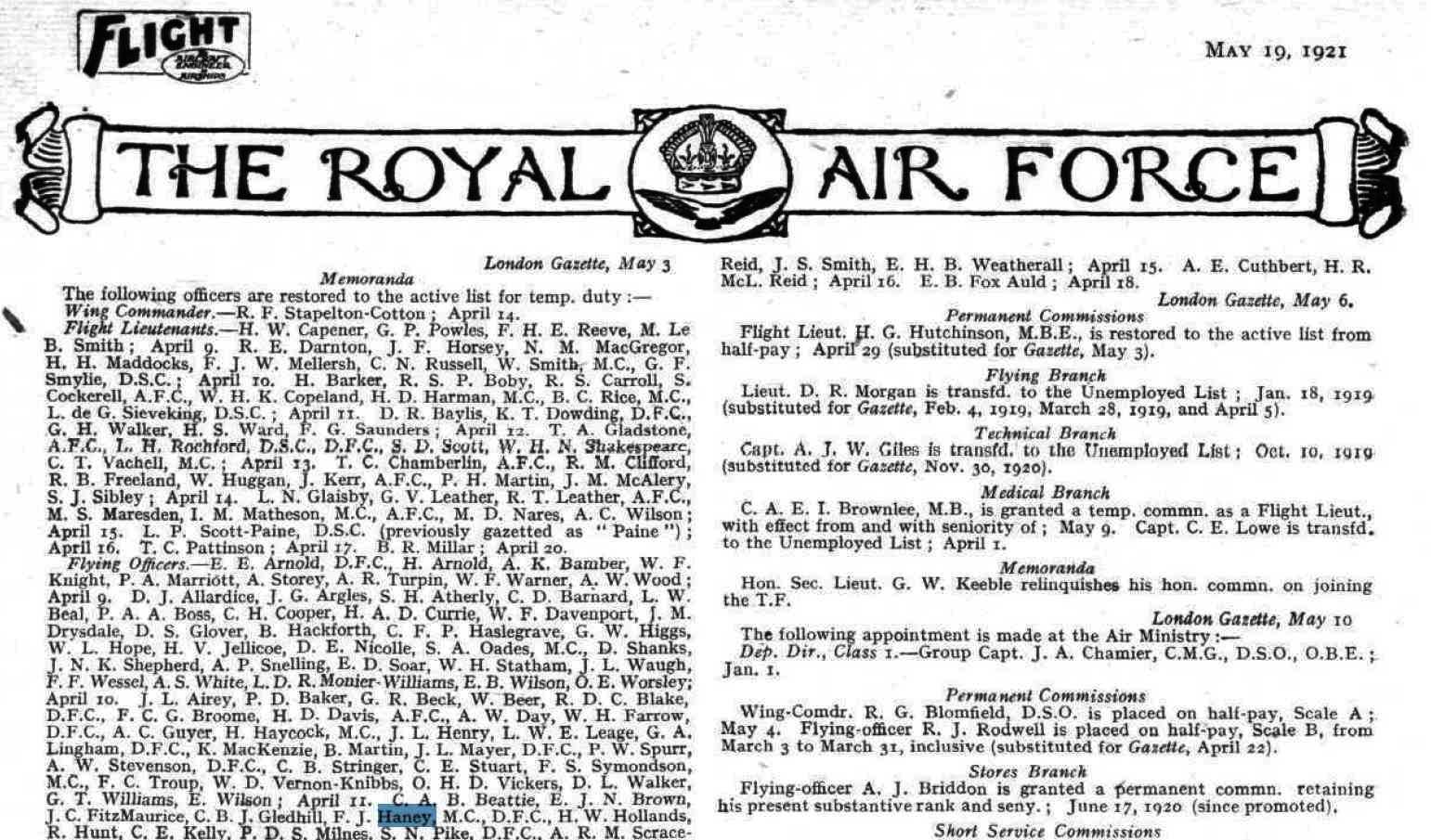

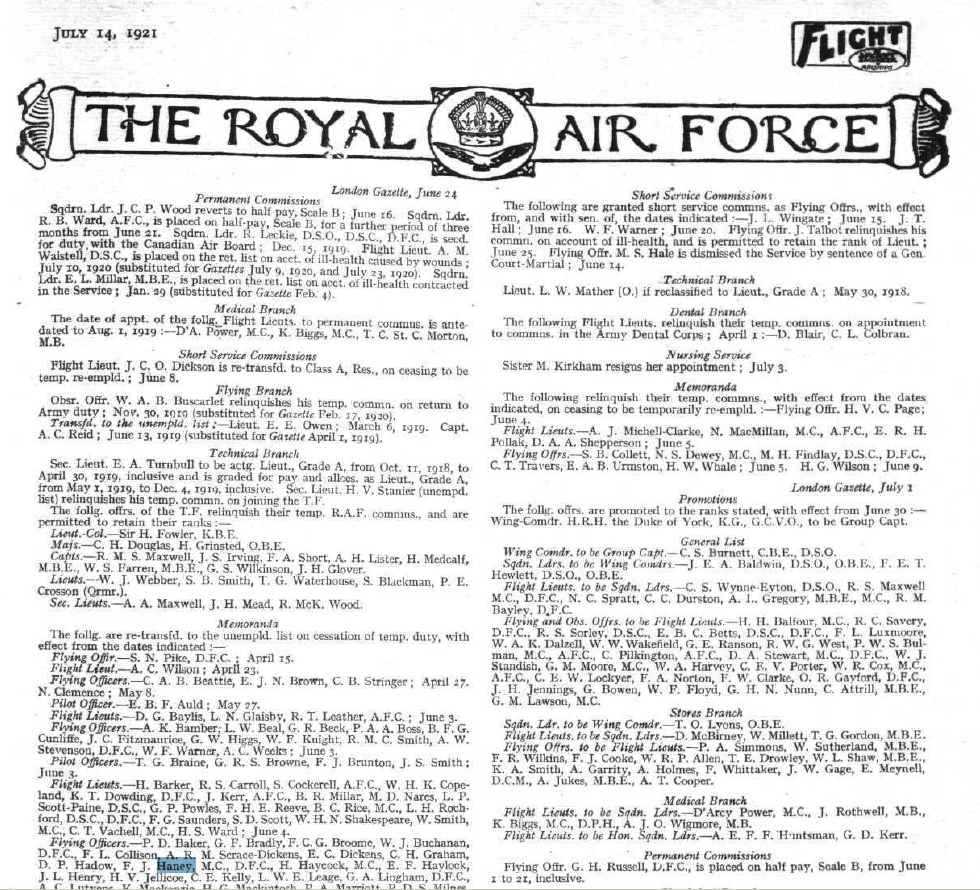

Flying Officer Temp Duty 1921

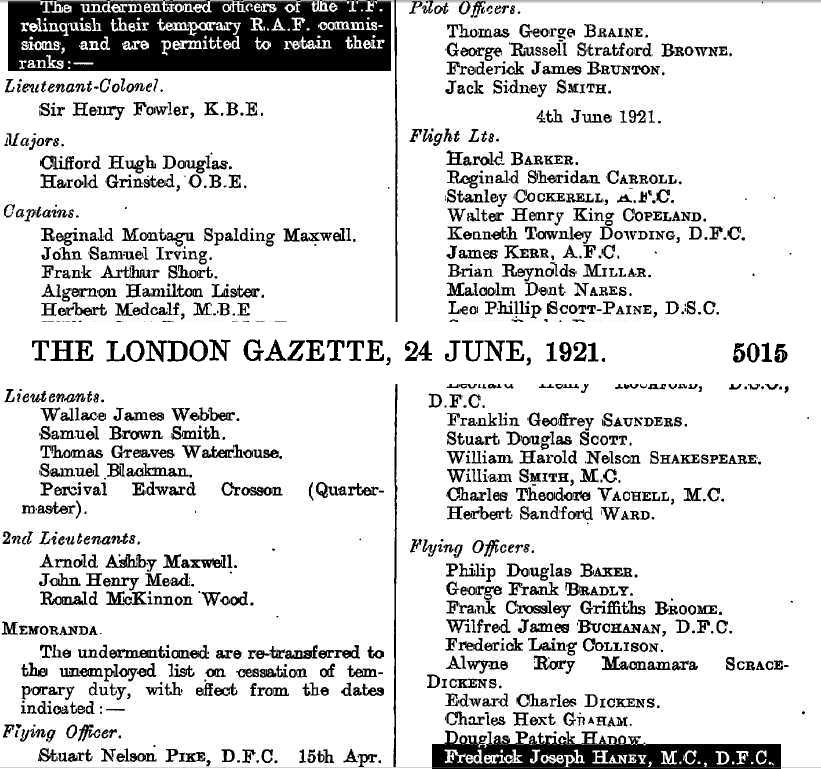

Commission Relinquished 1921

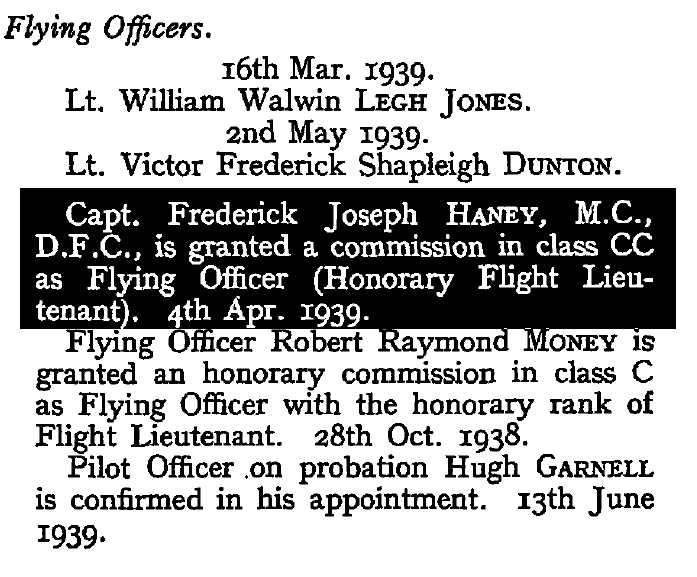

Flying Officer Commission 1939

Special Duties Commission 1939

Honarary Flight Lieutenant 1939

Haney Becomes an Inventor - 1940

Records retrieved from the National Archives in Kew were only released to the public domain in 1984:-

During the early part of 1940 it became almost impossible for pupils to put in the necessary hours night flying to qualify as pilots, owing to enemy action at night. Many Flying Training Schools were under orders to leave the country to do the necessary training abroad. It was imperative and urgent, that some way should be found to enable night flying training to take place.

In May he suggested to 25 Group Flying Training Command that night flying could take place during daytime, and started making experiments with filters at South Cerney. In June he was told that the same idea was being experimented with, at Peterborough and was ordered to collaborate with the people there, Messrs. C. H. and A.W. Wood.

His invention was for combinations of filters to allow only those wavelengths of light in the sodium region of the spectrum to pass through. Using these filters either in glasses to be worn by the pilot, or in panels in a blacked out aircraft, to produce the effects at night (Sodium lamps were used as landing lights.)

After the war he made a claim to the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors and was given a ex-gratia payment of 250 pounds.

See Appendix Schedule "A"

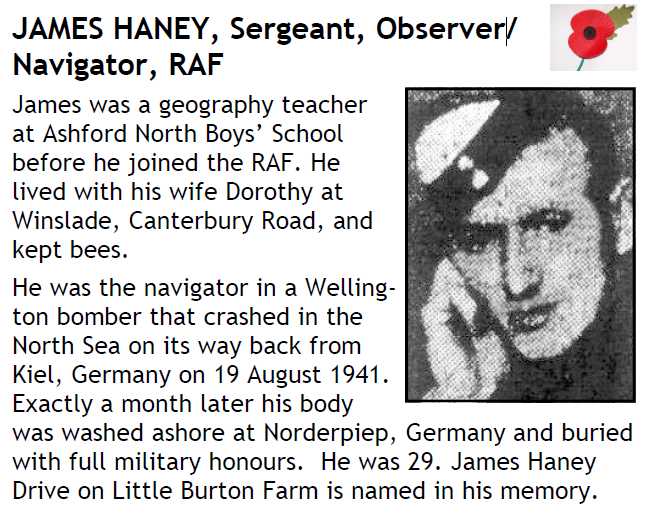

There is a road in Ashford Kent, named after James Haney (James Haney Drive)

Article from http://kennington-st-marys.org.uk/docs/archive/kenningtonwarmemorialKCEJS.pdf

HANEY, JAMES. Sergeant (Observer/Navigator), 1280935.

Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. 104 Squadron, Royal Air Force.

Died 19 August 1941. Aged 29.

Son of Frederick Joseph and Mary Waterworth Haney.

Husband of Dorothy Violet Haney of "Winslade," Canterbury Road, Kennington, Ashford. Kent.

Also commemorated on Kennington, Ashford, Kent civic war memorial.

Buried Kiel War Cemetery, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. Grave Ref: 2. G. 8.

James had been a member of staff at the Ashford North County Modern (Boys) School from 1934 until just prior to his enlistment in 1940. Ashford, Kent resident Dennis Hayward served in the same squadron (please see his brief commemoration), and who died only ten days after James was recorded as lost. James was a crew member of Wellington bomber W5416 EP-? which was flown by 26 year old Flight Lieutenant, William W. Burton, B.A. (Oxon.), R.A.F.(V.R.) of Retreat, Cape Province, South Africa. The bomber took off at 2240 hours on 19 August 1941 from R.A.F. Driffield, East Yorkshire, on a bombing mission to Kiel, Germany. Although James is recorded as dying on 19 August 1941 by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission this is in fact erroneous albeit by only a few hours, as contact had been made by his aircraft at 0318 hours on the morning of the following day, when a wireless transmission trying to raise R.A.F. Bircham Newton, Norfolk was made by the aircrafts crew. So far (February 2003) no trace of the lost Wellington has ever has been found, but it is assumed to have crashed over the North Sea. On 19 September 1941 exactly a month after his aircraft had taken off on its last mission James body was washed ashore at Norderpiep, Germany from where he was laid to rest with military honours at Büsum, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. James family were informed of his death and burial via the International Red Cross, since the war his body has been moved to Kiel War Cemetery, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. All five of the other men who perished with James have no known graves and are therefore commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial.

Article from http://www.kentfallen.com/PDF%20REPORTS/ASHFORD%20NORTH%20SCHOOL%20WW2.pdf

Squadron Leader (Temp) 1941

Excerpt from "A History of Police Aviation"

See Appendix for full chapter

The experimenting with wartime street lighting tailed off as lessons were quickly learned. On October 21, 1941 Scotland Yard managed to arrange for their Mr Haines to undertake a one and three quarter hour ride with an RAF crew undertaking an aerial survey of the London area from Northolt. Flight Lt. Haney was undertaking a similar task for the Air Ministry; the pilot was Squadron Leader Whitham. It was police co-operation, in arranging the setting out of ground marker lights for the flight, which alerted them to the availability of a spare seat. Being the first time he had witnessed the spectacle from the air, Haines was horrified at the extent of light leakage, particularly from moving motor vehicles. As the enemy was by now a rare visitor to the night skies of Britain it was officially decided by the police side not to make an issue of the situation. Logic suggested that should the raiders actually re-appear in any significant numbers there would be a massive, and voluntary, revision of the 5 situation by those on the ground. Nonetheless, from somewhere, reports which can be attributed to this flight were leaked to the newspapers less than a week later in an apparent effort to stir the public into being a little more Blackout conscious.

Following on from this flight, in April 1942, the RAF teamed up with the Metropolitan Police and the Ministry of Home Security to undertake tests relating to vehicle lighting and aerial observation. Ten Humber police cars, their lighting illuminated and masked in a variety of ways, were driven around Croydon Airport perimeter track as an RAF observer, Squadron Ldr. F J Haney, looked on from above. The results merely showed that whatever form of mask was employed, those attached to police cars being correctly fitted - were far more efficient than those observed on privately operated traffic passing by Croydon Airport on the public road. Towards the end of the war, in May 1944, throughout the nation thoughts were straying towards peacetime activities and renewed attempts were made to set up a Metropolitan Police Flying Club. All too well aware that, contrary to earlier appreciation’s, police of all ranks were now serving in the military and in the air in large numbers, thought was given to the possibility of channelling these skills in the days of peace to come. As in the case of the late 1930s proposals, this scheme, wholly based upon the use of Slingsby built gliders, was to be investigated for a few months before finally being abandoned in the depression of mid-1946.

F/Lt F.J. Haney was mentioned in a special despatch on 1 January 1945 and commended "For valuable service in the air".

Flying Officer Commission 1945

Commission Relinquished 1946

WW2 - Fred's Secrets and Deception ?

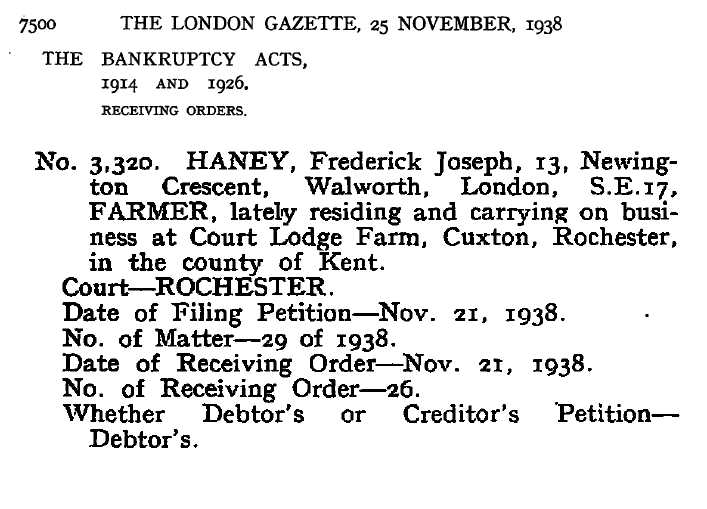

In 1938 Fred was a farmer up for bankruptcy in a London Gazette listing, probably an unfortunate experience for him but he managed to get it discharged after the war in 1952.

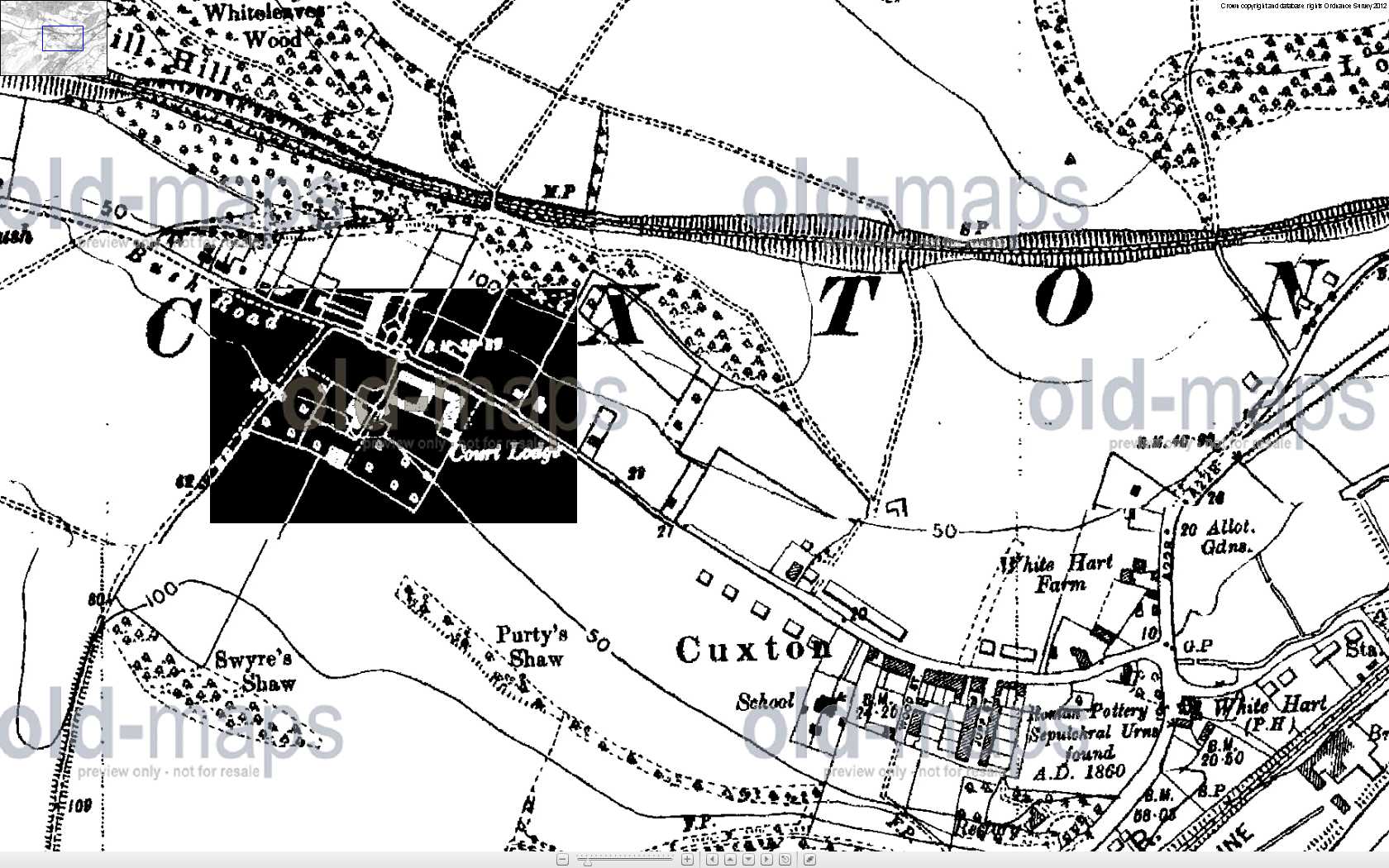

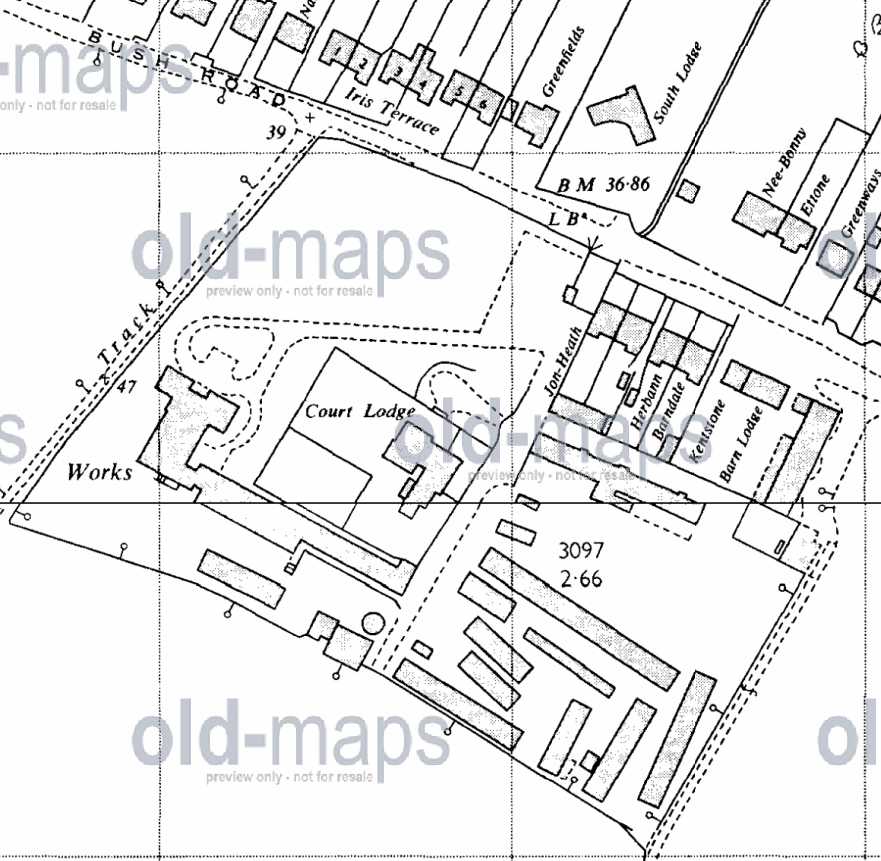

Subsequent research on 'his farm' makes me think this was an act of deception. Between 1936 and 1940 the famous Stirling Bomber, the first four-engined Heavy Bomber of the Second World War was being built by Short Brothers nearby at Rochester. Their design and blue print office was concealed at his Court L0dge Farm.

[old-maps.co.uk]

The site was taken over by the RAF and the first airframe for the Stirling Bomber was assembled here, note the 'fuselage' shaped buildings in the backyard.

[old-maps.co.uk]

After the war the site was used by plastic and paint factories and is now a housing estate. I'm almost certain Fred "took one for the boys", and I take my hat off to him.

The Archivist at the Stirling Bomber Organisation notes "As to the Shorts office in Cuxton I am trying to find out a little more about the location. It was unknown to myself before today and a fellow researcher had never heard anything about it. Being a satellite away from the main drawing office there may not be much information relating to it."

Fred died in 1969 in Cuckfield, Sussex.

|

|

|

Sqd Ldr F.J. Haney MC DFC

(1886-1969)

Appendix: A History of Police Aviation

War and Peace

Not every nation was at war in 1939, many were reluctantly dragged into the fray at later stages. Other than a significant number of volunteers the USA managed to keep their people out of the direct conflict until 1941.

Of the immediate combatants in Europe only the British and Germans had prior police flight knowledge, the Austrian operation having been incorporated into the Reich in 1938. Contrary to Trenchard’s intentions earlier in the decade, the British gave up all independent police flying and did not actively seek cooperation with the RAF.

In Germany the situation was somewhat different. After losing a large proportion of its strength to the formation of the Luftwaffe in 1935 and beyond, the police air units remained in being as flying units into the war years. Where, before the dismantling of the original formations, units had enjoyed the use of the most up to date flying machines, the independent force that remained was reliant on caste off second line military equipment. Known wartime equipment included

Junkers Ju52/3m transports, and a variety of elderly liaison types from Focke-Wulf, Siebel and Fiesler. Reflecting the earlier front line fighter equipment the police also had at least one Messerschmitt Bf109 on strength. The known example [D-POL-98] was an early model 109B that would be unlikely to have acquitted itself on equal terms if faced with an enemy air force. Unlike its Allied counterparts, the German police air arm was effectively a military unit which, like the whole of the German nation, became increasingly embroiled in front line war duties as the war progressed. At what stage it ceased to exist as a separate entity is unclear.

The Cierva Autogiro’s gathered at Hanworth were soon called up to join twelve similar machines acquired by the military as Avro C-30 Rota’s earlier in the decade. Each was called upon to serve in a vital role in defence of the British Isles. The C-30’s ability to fly at very slow speed was identified as a significant feature in the calibration of the new British secret weapon Radio Direction Finding [radar]. The years of plodding slowly backwards and forwards in this vital role took their toll on the fleet, both the impressed civil machines and the military originals. By the wars end only a dozen of the mixed fleet survived. Not all aspects of police flying were stopped by the war. The Joint Home Office and Illuminating Engineering Society Lighting Committee [IESLC] were authorised to undertake some live trials with the severely curtailed street lighting that a wartime blackout brought in September 1939. Having the wholly reasonable assumption that the imposition of total darkness nationally would severely hinder enemy air operations over the British Isles, emergency powers were enacted to force everyone to comply with the edict. For the majority of the war it became a punishable offence to show an unshielded light at night - come rainy or moonlit night, whether the enemy was believed present, or not. A great deal of police effort was directed to ensure this was kept to a minimum. Unfortunately, it did not quite work out in the manner predicted. On the ground a situation was created whereby in spite of some severely shielded street and vehicular lighting, the copious use of white paint to highlight obstructions in meagre illumination, and other aids, pedestrians and vehicles were hitting each other with monotonous regularity. Road fatalities soared.

3

Traffic in the days before the wartime clamp down was in any case little in volume, slow and poorly lit. The roads were narrow and rarely lit in other than major towns - and most of these only showed illumination during the first part of the night anyway, so a blackout situation was not a totally alien concept. It was the lack of flexibility, the adherence to the stringency of the rules at all times, that became the measure’s Achilles Heel. As was to be clearly demonstrated, viewed from the air on a clear night there was so much upward light leakage, undetectable from the ground, that it was probably not worth all the effort it took to police it.

Initially undertaken at street level in London, Blackout monitoring activity progressed to flights involving a number of separate bodies. Included were representatives of the police, the British Standards Institute [BSI], the Illuminating Engineering Society and the Wembley based industrial concern, the General Electric Company [GEC]. The IESLC initially operated alone but required the police to provide a waiver document called the Lighting Restriction Order. This document enabled them to undertake their experiments unhindered, but on the clear understanding that immunity ceased as soon as an air raid was signalled. If they should be a bit slow in returning the area to the requisite Blackout condition they quite likely to end up being issued with a summons to attend a court. It did not happen of course, if only because such tardiness noted by the enemy posed a far greater danger to the experimenters than any magistrate.

The actual outcome of the series of experiments that this work embraced between 1939 and 1942 only serves to highlight the woeful inadequacies that the Blackout conditions suffered from.

After a number of days experimenting in central and west London, interest shifted to the City of Liverpool in the North-West. In late October 1939 the City Lighting Engineer, Mr. Robinson, had devised a new type of street lamp hood which had been installed experimentally in Castle Street, Liverpool. As this hood device was of an unapproved type, it was agreed that a fuller installation would be set up elsewhere in the area and then viewed from the air in due course. Although it was well out of their own area, Sidney Chamberlain and E R Hooper of B Department maintained an active watch on this and other similar experiments set up across the length and breadth of Britain. The first aerial observation tests were to be undertaken over London on the evening of November 9, 1939. A range of lighting conditions were set up in selected areas of Westminster and Burnt Oak [near RAF Hendon] but, although 4 the ground operations went well, the task was not completed by the aircraft that night.

The Liverpool experiment was the first successful observation flight. Mr Robinson had set up the experiment in record time, the city managing to install all of the new equipment along a one and a quarter mile stretch of Speke Road and Speke Hall Avenue, beside the airport, in time for the viewing on November 17. Two flights were made from the airport. The pilot Captain Neish was accompanied by Hooper from the police in London and representatives from the Ministry of Transport, Westminster Council and Liverp00l City Engineers. The Liverpool design of cowls were considered a success, pending the viewing of the official BSI design when the Burnt Oak, London, experiment managed to get itself going.

The London aerial viewing finally got underway two days later, on the evening of Sunday November 19. A civil registered National Air Communications de Havilland Dragon-Rapide flown by Wing Commander J G Hawtrey took Hooper and J Waldram, a representative of GEC, up from Heston to view the street lighting in the Edgware Road. This flight was considered a partial failure due to the moonlight being brighter than the possible benefits expected from the street lighting. In spite of the supposed Blackout the observers were amazed to see a myriad of pin prick light sources escaping from the inky blackness below them. Two aircraft from Heston flew over the experimental street lighting on the evening of November 24. Again moonlight effectively outshone the dim street lights. The task was finally undertaken with a degree of success in a further flight from Heston on the evening of December 2. Hooper, accompanied by GEC’s Waldram and Wing Commander Hawtrey were passengers in a Rapide flown by Captain Ashley and his R/T operator during a three hour flight that allowed them their first glimpse of a dimly lit Edgware Road. The "Home Security" flights continued into 1940 with a variety of crew mixes and target towns. Witney in Oxfordshire attracted Sidney Chamberlain as observer in place of Hooper in March 1940, the former finding time in spite of an increasing workload of arranging wartime road convoys. The pilot was again Captain Ashley. Although the light searching was not of a warlike nature this activity effectively overcame an existing police taboo on "involvement" in war operations, thus embracing some parts of the Trenchard war proposals for police duties in time of war, set in the 1930s.

Early in the war Chamberlain gained an MBE for his war work with road convoys, and underscoring his status as a figure of some importance in civil hierarchy at Scotland Yard. Although observer duties were no longer to be his forte, he was still to re-appear on the police flying scene for another 20 years. The experimenting with wartime street lighting tailed off as lessons were quickly learned. On October 21, 1941 Scotland Yard managed to arrange for their Mr. Haines to undertake a one and three quarter hour ride with an RAF crew undertaking an aerial survey of the London area from Northolt. Flight Lt. Haney was undertaking a similar task for the Air Ministry; the pilot was Squadron Leader Whitham. It was police co-operation, in arranging the setting out of ground marker lights for the flight, which alerted them to the availability of a spare seat. Being the first time he had witnessed the spectacle from the air, Haines was horrified at the extent of light leakage, particularly from moving motor vehicles. As the enemy was by now a rare visitor to the night skies of Britain it was officially decided by the police side not to make an issue of the situation. Logic suggested that should the raiders actually re-appear in any significant numbers there would be a massive, and voluntary, revision of the 5 situation by those on the ground. Nonetheless, from somewhere, reports which can be attributed to this flight were leaked to the newspapers less than a week later in an apparent effort to stir the public into being a little more Blackout conscious.

Following on from this flight, in April 1942, the RAF teamed up with the Metropolitan Police and the Ministry of Home Security to undertake tests relating to vehicle lighting and aerial observation. Ten Humber police cars, their lighting illuminated and masked in a variety of ways, were driven around Croydon Airport perimeter track as an RAF observer, Squadron Ldr. F J Haney, looked on from above. The results merely showed that whatever form of mask was employed, those attached to police cars being correctly fitted - were far more efficient than those observed on privately operated traffic passing by Croydon Airport on the public road. Towards the end of the war, in May 1944, throughout the nation thoughts were straying towards peacetime activities and renewed attempts were made to set up a Metropolitan Police Flying Club. All too well aware that, contrary to earlier appreciation’s, police of all ranks were now serving in the military and in the air in large numbers, thought was given to the possibility of channelling these skills in the days of peace to come. As in the case of the late 1930s proposals, this scheme, wholly based upon the use of Slingsby built gliders, was to be investigated for a few months before finally being abandoned in the depression of mid-1946.

SCHEDULE "A" FORM 3.

Day Night Flying Training.

Additional Particulars of Disclosure of Invention (Para. 6)

In 1940 I was the Adjutant of the Advanced Training Squadron 3 Flying Training School. During the first half of that year we were unable to complete the night flying training of pupils, owing to interruptions caused by enemy raids.

About mid May 1940 I suggested to W/Cdr. Lester of 23 Group that it was possible to do right flying training in the daytime, by fitting up aircraft with complete blackout, except for a front panel to be fitted with suitable filters to cut out all light except light of a particular colour similar to that from goose necked flares at night. He encouraged me to experiment, and I was allowed to rig up a bathroom as an observatory in a vacant officers’ quarters overlooking the aerodrome.

I obtained dozens of filters from various sources, and for two weeks had little or no success in getting any light through the combinations of filters tested. In the first week of June 1940 I visited Lancegays, Ltd., London, and the manager kindly gave me a large assortment of foreign filters left over from work they had been doing pre—war. Out of this assortment I succeeded in getting a combination which gave an adequate blackout, yet showed streaks of fairly bright yellowish light running across when aircraft landed on the aerodrome. This was sunlight reflected from perspex of Oxford aircraft as they took off or landed. For practical purposes the light coming through approximated close enough to the light from goose necked flares, while the night conditions in the bathroom were satisfactory. I approached W/Cdr. Lester and told him that I thought I had satisfactory filters, and now must get a suitable source of yellowish light such as a sodium light.

Some time later I was told that people at Peterborough Aerodrome were working on similar lines, and that to save time and duplication of expense I must visit them and collaborate with them, as the night flying training was most urgent. I went to Peterborough and met C.H.Wood and his brother P/O A.W.Wood. I found that we were at the same stage of success, and they had two sodium lamps borrowed from the Bradford corporation, Their experiments had been made with Ilford Filters. Using the Ilford Chart of filter wave lengths, they had selected those which gave a good cut off except in the region of the sodium line. They were testing on the ground for range and visibility with various combinations of the selected filters. I was satisfied that we were on the same lines, but the Wood brothers had access to more filters than I had.

We agreed that C.H.Wood would do all the work in connection with obtaining more and better filters from Ilfords. P/O A.W.Wood was to contact various firms making lights and reflectors and deal with correspondence with Air Ministry officials and reports, etc., while I was to try for an alternative to the Sodium Lamp by testing the possibilities of a sodium flame, and also to do all the testing for visibility from aircraft. At the time this seemed to be a fair division of labour which might hasten the completion of the work.

In July I tested various filters from the air for range and visibility with a landing path of sodium lights. Other visits were made in August to discuss:- types of Landing Lights; Progress on the sodium Gas flame and the method of using the filters. My idea was to use them in one stage, viz: complete blackout of machine with filter panel in front, so that the pilot could see his instruments normally, as in night flying. The Wood brothers wanted a two stage method: Fitting the filters in glasses made by G/Captain Livingstone.

I made my last visit to Peterborough on 11th September with W/Cdr. Beresford to make observations with the glasses and to have a talk with the Wood brothers. At this visit I felt that the Wood brothers were rather evasive. I never managed to see any official correspondence regarding the attitude of the Air Ministry officials to the methods of using the filters, and I do not believe that the Wood brothers ever suggested using the filters, except in the way they suggested. I could get no information from them except that the Air Ministry officials had not yet made up their minds.

By 11th September the whole subject was no longer a matter of urgency. The problem of night flying training by night had already been solved in the first week of August, and night flying training was now going on normally owing to my Invention of Hooded Flares. As I had my work as a Squadron Adjutant to do while all this work was going on, I could find little time to visit Peterborough again. I understood that the Wood brothers had nothing to do except the Day Night Flying business.

Other problems arose in connection with the Blackout of Gas Works which kept me busy at South Cerney in October and November. On 9th December I was posted to the Air Ministry, Whitehall, for flying duties in connection with black out problems, so lost complete touch.

30/8/51 F.J.Haney

All Aliens RFC, Seft0n RUFC photographs, programmes and memorabilia Copyright © 2012 Sefton RUFC