Alien not Shaken and certainly

not Stirred

Written and researched by David

Bohl,

with the kind help of the Rule family tree and historians world wide.

The

intruguing story of E.A.Martinez

starts with his Uruguayan father, also Eduardo, moving from his

Consular post in Vigo, Spain to Glasgow in 1912.

Eduardo Snr became Consul in Liverpool in 1917, and his relations with

the shipping and commercial community of Merseyside were always most

cordial. He reached retirement age but in

appreciation of

his valued services, his Government asked him to continue in office (he

completed 25 years in total). He was greatly attached to

Liverpool, and had intimated that he would not accept promotion

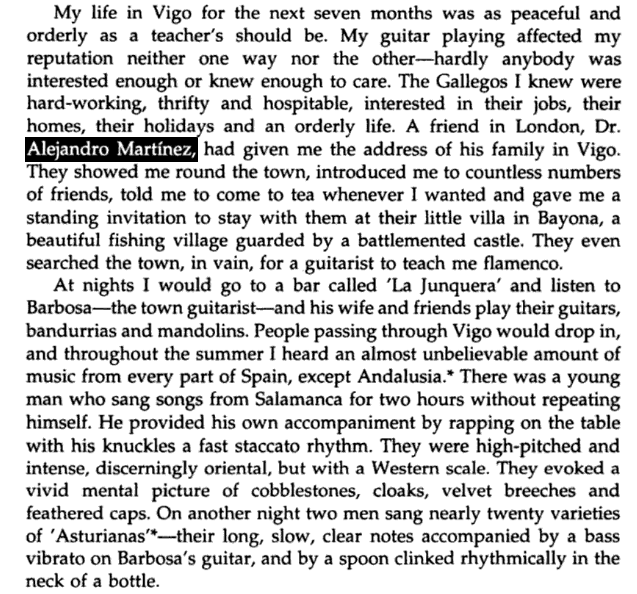

involving his departure from the city. For many years, he and his

family lived in Alexandra Drive, Sefton Park with his wife, eight sons,

and three daughters. Seven of his sons were educated at Liverpool

University.

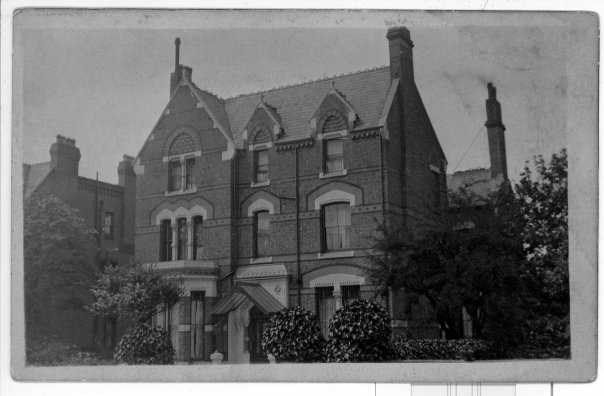

["Alhambra"

- Photo courtesy of the

Rule Family

tree]

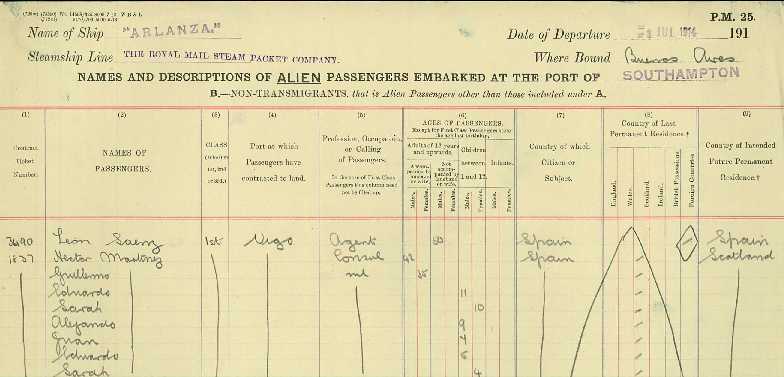

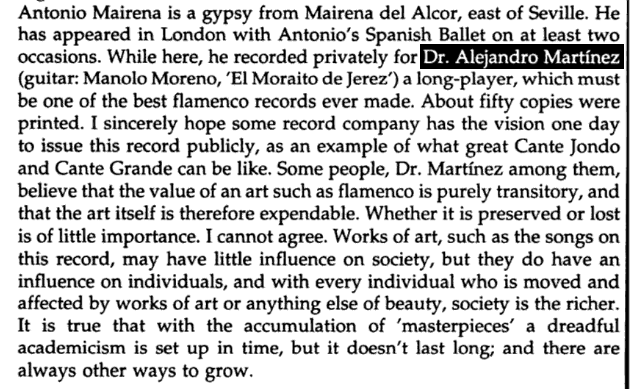

[Photo

courtesy of the Rule Family

tree]

Back Row: Sarah,

Eduardo Alonso, George

and elder brother

[The

children going on holiday to

Vigo in the summer of 1914]

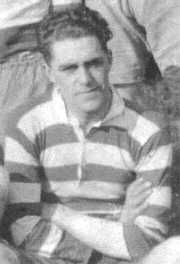

Born in Vigo in 1903, Eduardo Martinez Alonso entered Liverpool

University to study medicine in 1918 and together with elder brother

George (b.1902), joined the Aliens shortly after their reformation in

December 1919. Their younger sibling Alejandro Juan started playing at

the

first opportunity in 1920 with Arthur(perhaps a cousin) playing in

1923-24.

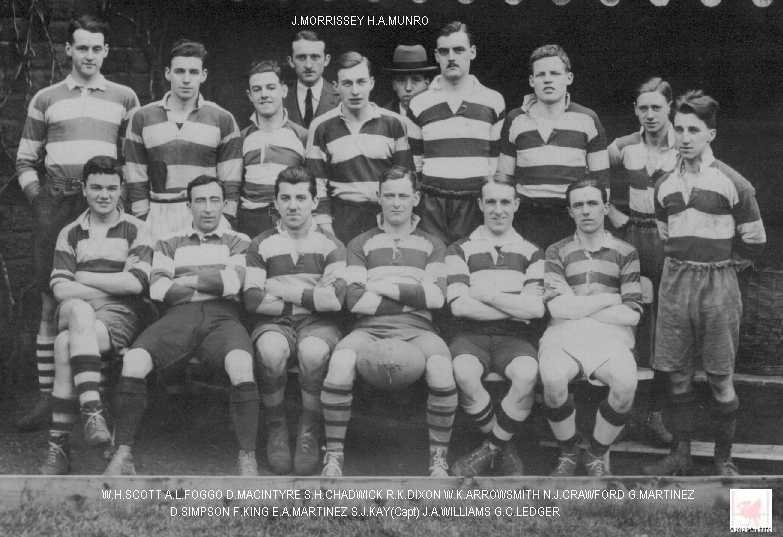

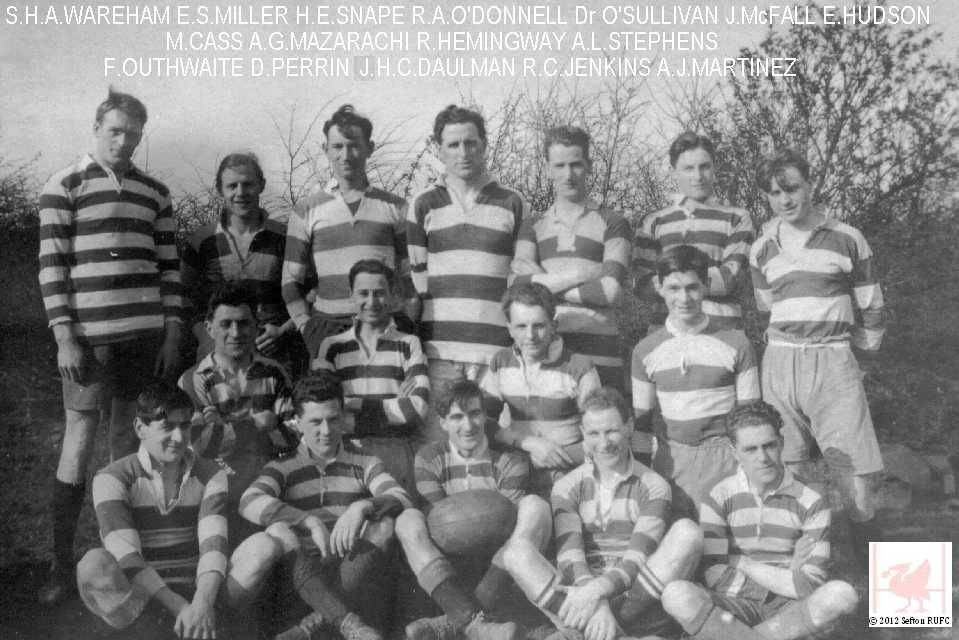

[1XV

- 1920/21 Eduardo and George]

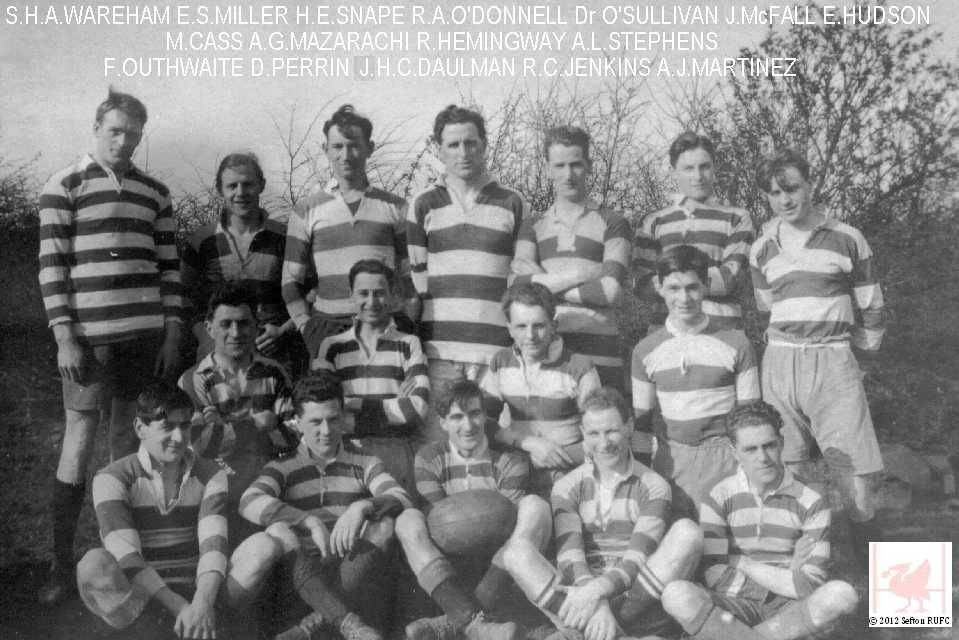

[1XV

- 1920/21 Alejandro]

SEFTON

"A" v. WIGAN OLD BOYS

"A."

Played

at West Derby, ending in a

pointless draw.

Teams:-

Sefton "A": Kidd, Ovey,

Scotson, Morrisey,

Fraser, E

A. Martinez (captain),

G.

Martinez,

Kay, Darbyshire, Cornick,

Simpson, Snape, H. W. Jones, V. Jones,

and Price.

Wigan

Old Boys 'A': F. Payne, I.

Dodson, G.Scott, H.

Scott, H. Booth, J. H. Roberts, H.Baxendale, A. H. Crawshaw, W. Lang,

A. R. Martland, J. Lea (captain), H. Peacock, H. Leyland, E. Lupton,

and A. Goodyear.

The

Wiganers were up against a stiff

proposition

in that their opponents had not lost a match this season. The game was

of a gruelling nature, and only the determined tackling of the visitors

kept Sefton out. The brothers Martinez were a clever combination and

took a lot of stopping. The Old Boys certainly deserved all praise,

especially as they had two tries disallowed.

Wigan

Examiner 24/10/1922

When

Eduardo qualified in Medicine he was uncertain

what his

next step should be, and his

mother, possibly keen to free up a little space in the house where he

lived with his two older and eight younger siblings, suggested that his

grandmother in Madrid would be delighted if he went to stay with her.

In September of 1924 both Eduardo and George resigned from the club.

Taking the huge hint off his mother Dr Martinez set off for Madrid and

took further medical degrees. He was soon in high demand as an English

speaking physician, one of his patients

was Queen Ena, the British wife of King Alfonso.

In

normal circumstances we could usually finish this

life story off with one sentence and say he continued to be a

successful thoracic surgeon in Spain, but, he published a book in early

1960's illustrating heroic service to the Allied cause in the

Second World War.

'Adventures of a

Doctor' is a very rare

book to find, but luckily a precis has been written recently

by Caroline

Angus Baker

Just in case the link disappears in the future here is the review in

full, our great thanks to Caroline:-

EDUARDO

MARTÍNEZ ALONSO

SPAIN BOOK REVIEW: ‘Adventures of a Doctor’ by E.

Martínez Alonso

PUBLISHED ON February 18, 2014

[Adventures of a Doctor

by Eduardo

Martínez Alonso seems to be so rare, I can’t find

any

cover art or a blurb about this book. I managed to purchase a damaged

copy from the New Zealand parliamentary library, and when they tossed

this book to me for a mere $6 (about €3.60), they obviously

didn’t know what a treasure they had. Eduardo

Martínez is

quite an extraordinary man with a story that seems to have been largely

lost. With the market flooded with 1001 Spanish civil war books, it

comes as a great surprise that this book doesn’t get more

recognition.

The

story starts

with the author born in Vigo, Galicia in 1903. His father was from

Uruguay, and was the consul in Vigo. As a young boy,

Martínez

travelled to his father’s homeland, along with his family (he

was

one of eleven children, and talks of his mother constantly having to

nurse his siblings). The story tells of life in northern Spain in the

era, and exploits with his brothers and attending a boarding school

with mixed success. In 1912, Martínez’s father

received a

post to Glasgow, and the whole family moved north for a new life.

Martínez dreamed of working in hotels or on ships, able to

meet

people and travel far and wide. He became bilingual at a young age,

seeing the benefit of speaking Spanish, English, French and more. But

it was his father who said he would be a doctor, not a sailor. As each

of the eight boys grew and carved out professions (sisters, of course,

were to be wives and caregivers), the prophecy of the hard-working

consul came true. The family and Martínez recalls the first

world war, his school years and an eventual trip back to Uruguay.

As a

trained

doctor, Martinez moved to Madrid with his grandmother, and speaks of

seeing Anna Pavlova dance at Teatro Real, with the King and Queen in

attendance. He quickly took up a post at Red Cross Hospital, and met

Queen Ena, British wife of King Alfonso XIII, and the Duchess of

Lecera, who were delighted to have an English-speaking doctor. News

travelled of an English-speaking doctor in favour with the queen, and

Martínez was in hot demand. Just eighteen months later,

Martinez

graduated from San Carlos Medical Facility and while meeting the King

and Queen socially and professionally, was appointed the medical

adviser to the royal family. This proved to be an amazing and dangerous

post.

When

the Second

Spanish Republic was founded in 1931, Martínez was in the

palace

in Madrid with the royal family as they were deposed. He tells of

sitting casually with Queen and princesses as the monarchy fell. As the

family were forced into exile and as Spain underwent revolution,

Martínez’s position as a monarchist him an easy

target. As

civil war came five years later, things changed dramatically.

Martínez got his family out of Spain in July 1936, or off to

the

safety of Vigo, and knew he would be in danger as a former royal family

aide. Through his work for the Red Cross, he was ordered by a Communist

faction to work as a doctor for the Republican side of the war.

On

Saturday morning

the shooting started. We sat in a bar and heard the crackling of

machine guns, the burst of hand grenades, and I saw smoke arising from

many quarters of Madrid. By Monday morning a general strike had been

called. Everything was paralysed except murder, arson, and rape. The

Spanish civil war had commenced – Pg 70

Martínez

talks of watching a church burning as priceless works of art were set

alight along with the riches of the churches of Madrid. He saw a priest

thrown on the flames but was unable to save his life when he pulled the

screaming body from the blaze. Most priests were taken out to Casa del

Campo to be shot. Men were burning priests but trying to revive pigeons

which fell from bell towers, overcome by smoke. Martínez had

an

apartment in Madrid, and he hid as many people as he could throughout

the war. Nuns and priest were hidden, and forced to serve meals to men

who sat and spoke of vicious murders they had committed against the

clergy.

Martínez

was

posted to a town outside Badajoz, Cabeza del Buey, in the south-west,

working for the Communists. While running the hospital, a young nurse,

Guadalupe, suggested they flee and work for Franco’s troops

instead, but Martínez seemed convinced that he would be

killed

at some stage, regardless of where he was posted, and claimed no

political alliances. In Cabeza del Buey, he was forced to attend mass

executions of seemingly innocent men, and despair at violent speeches

about revolution and vengeance. He performed many surgeries and saved

lives in the most atrocious conditions. But with no warning,

Martínez was shipped off, with Guadalupe, and sent to

Ocaña, just outside Aranjuez, to work in the prison there,

and

be a prisoner himself. As he had in Cabeza del Buey, Martinez managed

to get some nuns freed from prison to work as nurses, and treated

patients while living in a cell himself. Between dire conditions and

deadly activities, a patient told Martínez that his turn to

be

executed was near. An in understated manner, Martínez talked

of

his prison escape to Valencia in March 1937, were he managed to procure

a fake passport and get aboard the Maine, a ship bound for Marseilles.

Martínez

quickly got himself back in Spain, despite the dangers. He chose to

cross the lines and work for the ‘white’ side of

Spain,

Franco’s rebel army. Red Spain (the Republicans), he felt,

thought nothing of him, his work, and long suspected their cause would

lose the war, one they never had a chance to win. Posted to Burgos,

Valladolid and then San Sebastien, Martínez then found

himself

working on the front lines as Franco’s army continued to

advance

into enemy territory. Towns fell one by one as Martínez

fought

to save lives, but writes in such a humble, unassuming manner. Once in

Zaragoza, Martínez worked hard to care for patients at the

hospitals, and pioneered the use of closed casts on wounds, a procedure

first tried with less success twenty years earlier. Despite the smell

offending wealthy female volunteers, Martínez’s

experiment

helped the lives of many patients otherwise in agony as they recovered.

He was then moved on to his own mobile surgical unit in Teruel in 1938.

Martínez

was

there on the ground when troops stopped in Sarrión, 100kms

north-west of Valencia, as the war finally came to its brutal end. On

April 1st, 1939, the war was over and declared won by Franco in this

small town, and after helping a man and his son to Valencia,

Martínez sought out all those who had helped him during the

war,

and moved back to Madrid. No sooner than Martínez had helped

his

friends and former nurses, and begged for clemency for some condemned

to death by the new regime, the second world war broke out. With some

family in Vigo and some Britain, travelling on multiple passports,

danger was again faced. As Hitler plowed through Europe, Madrid

suffered greatly after the civil war and Martínez went to

work

at Miranda de Ebro, near Burgos, to help war refugees from all nations.

With such a humble attitude, he glossed over his feat to aid refugees

out of Spain, saving their lives, until in 1942, when his ferrying of

innocents was discovered and he was forced to flee Spain. His time

working with British Naval Attaché, Captain Alan Hillgarth

is

barely touched upon, but should surely serve as an incredible tale of a

man saving lives at great risk to his own. This two-year period alone

could serve as a story all of its own. Just his dramatic escape would

serve as its own story, but the author covers it in a few sentences,

and neglects to mention he fled with a new wife. He also failed to

mention his first marriage which produced two children, but was

annulled after Franco took power in 1939 (His wife was a British woman

who went home without him). I only found about either marriage after

studying the doctor further myself. There are no clues to whom these

women are at any point in the book. His personal life is never touched

upon.

Again,

Martínez talks little of his involvement with the rest of

the

world war, after being detained when first arriving in Britain (no idea

if his Spanish wife was also detained), but worked as a spy for Britain

throughout and barely talks about it. He worked at Queen Mary Hospital

after the war and oversaw great new procedural advances, meeting some

of Europe’s finest surgeons, but then returned home to

Madrid.

Life was hard in the beleaguered nation, and he again went to work at

Red Cross Hospital, specialising in chest surgery. He then moved on to

working as the doctor for the Castellana Hilton, newly opened in 1953.

He recounts stories of wealthy Americans, and famous movies stars

(unnamed) alike, who came to Madrid for all sorts of reasons. He spoke

with frustration at his patients demanding penicillin shots, not

wanting to discuss why they need this medication. Many guests, male and

female, had a penchant for sleeping around and wanting medicine to

atone their sins, either before or just after the liaisons which bore

infections. One guest talks of being raped and demanding penicillin,

though the story is far from convincing to the doctor. Sexual

liberation had come to the foreign guests at the Hilton, and expected

Martínez’s penicillin to cover it up. He makes his

disdain

clear for these patients and the abuse of this groundbreaking

medication, and of the myriad of alcoholics he was forced to attend to,

when little could really be done for them.

The

book is written

in the manner of a doctor – no-nonsense, no fussing with

detail,

just the raw facts given out without prejudice. Martínez is

a

man with the story worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster, but it

wouldn’t be his style. This book was written in 1961, and

Martinez lived until 1972. It shows what really stood out to the doctor

in his life, because details are excluded, and there are many secret

operations he simply never wanted to discuss. He is free and easy with

dates – because I know the civil war, I could piece together

the

timelines of the book, but needed to look up world war details and the

opening of the Madrid Hilton, just to give myself an idea of how much

time passed between chapters.

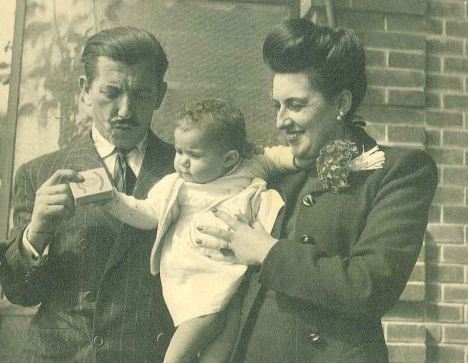

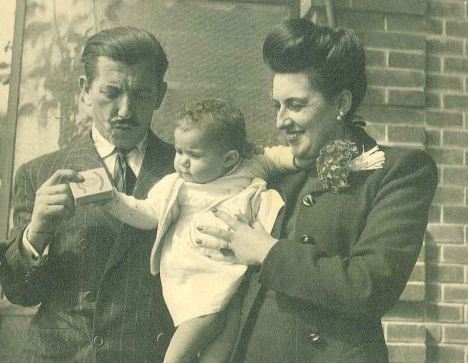

*above photo taken just prior to release from the Spanish army, 1939.

Photo supplied in the book (page 112)]

So

it looks like we have a real life

Spanish episode of "Hola, Hola"

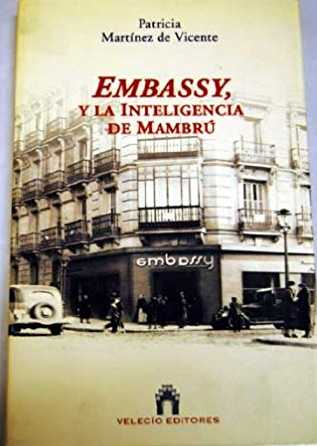

on our hands, but the lid really came off events in 2005 when

a

Special Operations

Executive file held at

the National Archives in Kew was de-classified.

Martinez’s

daughter, Patricia

Martínez De Vicente became aware of this and after

a

lengthy trawl through all this unknown

fascinating information she wrote a book called "The Enclave,

Embassy".

Another

online article by Nicholas Coni

combines 'Adventures of a

Doctor' and 'La Clave, Embassy' entitled Surgeon

Who Undertook Special Operations

Once again just in case the link disappears in the future here is the

page in full, our great thanks to Nicholas:-

Surgeon

Who Undertook Special Operations

Correspondence:

26 Brookside,

Cambridge CB2 1JQ, UK

(email Nick.coni@ntlworld.com)

[Although

he was

born in Vigo in 1903, and although his name and

ancestry are Spanish, Eduardo Martínez Alonso qualified in

this

country

and a curious sequence of adventures led him to pursue his career in

Spain and to his heroic service to the Allied cause in the Second World

War (WWII).

Education

and early

professional life

Eduardo’s

father, a lawyer, was posted to Glasgow as the Spanish

Consul

in 1912, but was subsequently transferred to Liverpool, and after his

school days in Scotland which he describes well in his

memoirs¹

(the

present account is based on his book and that of his daughter²

except

where other references are given), the young man entered Liverpool

University to study medicine in 1918. When he qualified, he was

uncertain what his next step should be, and his mother, possibly keen

to free up a little space in the house where he lived with his two

older and eight younger siblings, suggested that his grandmother in

Madrid would be delighted if he went to stay with her. She was a

well-connected lady, her uncle having been one of the many young

officers who attracted the attention of Queen Isabella II and having

become a general, a duke and the Viceroy of Cuba. While staying with

her, Martínez was introduced to the Chief of Surgery at the

Red

Cross

Hospital, which had been founded by the patron of the Spanish Red

Cross, King Alfonso XIII’s wife Victoria Eugenia of

Battenberg

(“Queen

Ena”, grand-daughter of Queen Victoria, born in Balmoral

Castle

in 1887

and, as events would show, a carrier of haemophilia), who visited

almost daily. She seems to have been pleased to meet an

English-speaking doctor and offered him a position as an intern in the

hospital, and while in this post he graduated from San Carlos Medical

Faculty, Madrid, and embarked upon his surgical training. His

grandmother obligingly moved to a larger apartment which could

accommodate his consulting rooms as well as the x-ray machine which she

bought him. Here, he performed minor procedures when not assisting at

major operations at the hospital, and it is clear that his practice

flourished; he visited surgeons in Paris and London, and was appointed

medical adviser to the British and American Embassies. He met the King,

helped to look after a close relative of the Queen, and was informed by

her that she had recommended to her husband that he be nominated

medical adviser to the Court – when, in 1931, the Monarchy

was

firmly

rejected by the electorate, the Second Republic was declared, and the

Royal Family hurriedly departed into voluntary exile.

Martínez’

memoirs are exceedingly short on details of his

personal

life, and he makes no mention of the marriage which he contracted to an

Englishwoman, ex-wife of a scion of the De-Havilland aircraft

manufacturer, with whom he had two children. She left for the UK, never

to return, and this marriage would become retrospectively invalid under

the new regime in 1939 as it had not been celebrated in a Catholic

church, leaving him free to marry a boyhood girlfriend from Galicia.

Civil

War

It does

not appear

to have been until the outbreak of the Civil War in

July 1936, that the upheavals that were ravaging Spain, really started

to impact upon him. It became necessary to simulate a revolutionary

fervour that one may or may not have felt, and some flavour of the

times can be drawn from his account of a dinner party which he hosted

which is also described in strangely similar words by one of the

guests, a somewhat unreliable American journalist from the flat below.

The other guests were a couple of anarchist militiamen, whom

Martínez

had clearly thought it prudent to invite, and who, under the influence

of their host’s liberal copas of Valdepenas, described the

unspeakable

barbarities which they had just been inflicting on two unfortunate

priests – blissfully unaware that the two maids who served

them

were,

in reality, nuns in disguise whom Martínez was sheltering

together with

a priest who was hiding in the next room. Martínez protests

throughout

his memoirs that he was at all times entirely apolitical – as

well as,

apparently, having been agnostic and somewhat anticlerical himself

–

and that he practised his profession totally indifferent to the

allegiances of his patients. There is no real reason to doubt him, but

our beliefs are conditioned to some extent by our upbringing, and it

was inevitable that his loyalty to the Republic would be suspect. This

was more than sufficient reason, in those terrible days, to earn a

denunciation and a summary sentence to a one-way paseo. He learned that

his name had been on a list of those to be executed, but scratched out

due to the intervention of the staffing officer of the hospital, who

was an influential communist and who demanded in return that he offer

his services to a communist surgical unit.

Thus it

was that he

found himself surgeon to a field hospital near

Badajoz, where his most distressing duty was having to witness a mass

execution in his capacity as Medical Officer (MO). His nursing

assistant and confidante suggested they cross to the other side, but he

responded that they were needed more where they were, and that in any

case, if they crossed the lines they were bound to be shot by one side

or the other. He attended to a stream of casualties from the front

line, but was shortly arrested and thrown into a jail in

Ocaña,

just

south of Aranjuez, where he organised a prison hospital, liberating

some incarcerated nuns to help him, and soon became free to visit

nearby military units. The engineer officer in charge of the

maintenance of the ambulances had been a taxi driver at the Palace

Hotel in Madrid whom he had often employed, and one evening while they

were dining together, the engineer was approached by a group of

anarchists who attempted to persuade him, by shooting him through the

jaw, that he should issue petrol to them in the line of duty, rather

than sell it to them. As Martínez was attending to his

wounds,

the

engineer advised him that he must escape as soon as possible or he

would be taken on a paseo.

Escape

to “White” Spain

When

Franco’s

troops crossed to the east bank of the Jarama on

the 11th

January 1937, the International Brigades bore the brunt of stopping

their advance, and it soon became widely known that there was a prison

hospital at Ocaña where the head surgeon spoke English. This

became

designated the main evacuation centre for casualties, and beds were

freed up by the simple expedient of shooting the prisoners. Appalled by

this measure, and desperate for support in the management of the 400

casualties who arrived daily, Martínez sent cables to the

senior

MO of

the Republican Army, Dr Recatero, fiercely critical of his management

and demanding assistance. He was himself accused of criminal neglect,

and collapsing onto his bed after leaving theatre at about 3 a.m., he

was woken up by Recatero and his henchmen, who had come to execute him.

His former taxi driver appeared miraculously on the scene, and relying

on the eloquence, so persuasively used against himself, of a pistol

barrel, convinced Recatero that he should abandon his mission. The next

day, Martínez was driven to Valencia by his rescuer

disguised as

a

casualty, while café radios blared out his name and

description.

Furnished with a false passport, the British Embassy arranged passage

to Marseilles on HMHS Maine; from there, he travelled by train to St

Jean de Luz and thence was driven by the American Consul over the

border to San Sebastian, where he caught another train to Burgos. After

security clearance he enlisted in the Nationalist Army and was sent to

the Basque front, where he noted “…then came

Guernica,

which our German

allies erased from the face of the earth in a bombing raid which raised

an outcry throughout the world”. Following the campaign in

the

north,

he was posted as senior surgeon to a base hospital in Zaragoza, whence

he wrote to a medical friend in the UK:

“To

cut a

long story short, I broke prison on the 1st of March,

with a

little outside help and eventually reached Valencia where I literally

threw myself into the hands of the British Embassy. Finally I got

aboard the HMHS Maine which took me as far as Marseilles, and here I am

after nine months of campaign in the north, very happy to be on this

side and in the thick of things…Many of our friends of the

International Congress of the History of Medicine have been shot by the

reds…Please do what you can and help us stamp out communism

[e.g.

supply surgical instruments]…”(5)

Surgeon

with the Nationalists

In

Zaragoza,

“A team of distinguished and, in some cases, pretty

ladies

from the aristocracy … would come in every morning in

Nursing

Auxiliary

uniforms, don rubber gloves and face masks, fill syringes with hydrogen

peroxide solution, and go from bed to bed washing out the festering

flesh and rotting bone.”

All the

patients,

inherited from his predecessor, were suffering from

chronic infection of their wounds. Martínez, who claimed

that he

was

the first [in the world? on the Nationalist side? in that hospital?] to

practise “what was later called the ‘Spanish

cure’” [as described by

Trueta in 1939, but strikingly lacking Trueta’s emphasis on

débridement, a grave sin of omission even in a book for

laymen],

put

the limbs in plaster, and found over the next few days that the

patients were much happier, with normal temperatures and hearty

appetites, but that the distinguished ladies were very unhappy since

they had little to do but complain about the smell. One of them

reported her dissatisfaction to the medical superintendent, who

reported him to the chief MO of the sector, who posted him to a

hospital train, “the worst invention of the Spanish Civil

War”. It does

sound, from his description, as if the wagons had been very poorly

converted for use as operating theatres and wards, and that it was the

implementation rather than the concept which was at fault. His

complaints again earned him a rebuke and a posting, this time to the

campaign to recapture the frozen city of Teruel. There, he set up

hospital in an abandoned church and had to contend with numerous cases

of trench foot and gangrene as well as the wounds inflicted by enemy

action. His experience of serious trauma may have prompted him, some

months later, to write to his British friend requesting some pitressin,

clearly intended either as an established or experimental treatment for

shock.

After

the war he

was sent to Madrid, to food rationing and to a typhus

outbreak, to take over a Military Emergency Hospital. The epidemic was

due to the release of louse-ridden prisoners from concentration camps,

and his former tormentor, Colonel Recatero, was identified in one of

these camps, disguised as a “common militiaman” and

was

charged with

the execution of 29 doctors, and would undoubtedly have faced the

firing squad himself but managed to elude his captors for long enough

to leap from a fourth-floor window with a very similar outcome.

Second

World War

The

outbreak of the

war found him re-established in his practice in

Madrid where he was also the MO to the British Embassy and where, in

consequence, he was responsible for the medical care of British

subjects and other Allied servicemen who had entered Spain as fugitives

from Nazi-occupied Europe. The latter were interned in one of several

concentration camps, mainly that originally established for Republican

prisoners of war in a town near Burgos with the charming name of

Miranda de Ebro, which belied its evil reputation; designed for 500

inmates, it eventually held 3,500 in conditions of hunger, poor

sanitation and extremes of temperature which were in part, at least,

attributable to the economic plight of the country. On his visits

there, Martínez took provisions, cigarettes, and irons

capable

of high

temperatures to destroy the lice in the clothing being pressed.

There

followed a

period from 1940 to 1942 which Martínez

dismisses with

a tantalising lack of detail in his memoirs, through loyalty to his

comrades whose identities he was sworn to keep secret. During this

period he and the British Naval Attaché, Captain Alan

Hillgarth,

conspired to establish a most effective network through which they

spirited very substantial numbers of Jews from various nations, and

other fugitives including servicemen, agents, and persons of importance

to the Allies, through Franco’s pro-Axis, Gestapo-infested

Spain

to

Gibraltar, or Portugal, and freedom. Hillgarth and his colleagues in

the Special Operations Executive (SOE) may have been the prime movers,

but Martínez, with his contacts and knowledge of the

terrain,

and

motivated partly by anglophilia but mainly by sheer humanity, was the

organizing genius behind these proceedings. A great deal of information

about his clandestine activities has been unearthed by his daughter, a

social anthropologist, and although he never spoke about these

exploits, she fortuitously discovered his diary from that era when

selling his flat 15 years after his death in 1972. She pursued the

revelations it contained, through the interrogation of her mother, then

aged 80 but still possessing an excellent memory, as well as through

archival sources. Although her mother had known little of the nature of

Martínez’ undercover operations at the time, she

was able

to recall

many of the meetings and comings and goings, and, having maintained

contact with Hillgarth after her husband’s death, was able to

confirm

much of the account that her daughter was able to piece together.

Another friend who witnessed a number of what were at the time, to her,

mysterious events was Consuelo Alan. This lady’s mother, a

redoubtable

Irish lady called Margarita Taylor, ran a café rather

confusingly

called “Embassy”, frequented by the

élite of Madrid

society, and where

not only did the conspirators meet discreetly under the very noses of

the SS, but where many of these fugitives would be concealed for a

night or two before proceeding on their perilous journeys.

It is

necessary to

digress to outline the situation in Spain during the

early years of WWII. It may be too simplistic to say that Franco would

never have won the Civil War without all the assistance he received

from Mussolini and Hitler(6),

but it most

certainly helped, and there

seems to have been a strong possibility that Spain might have entered

WWII on the side of the Axis, in spite of a setback at the historic

meeting between Hitler and Franco at Hendaye in October 1940(7)

(Preston

1995: 393-400). Franco certainly made anti-semitic noises in some of

his speeches(8),

but it is far from clear

that anti-semitism formed one

of his core beliefs (if, indeed, he held any). Meanwhile, it was

Churchill’s profound hope that Franco would stay out of the

war,

and

this was the mission he entrusted to the ambassador whom he posted to

Madrid, Sir Samuel Hoare. Hillgarth also enjoyed Churchill’s

confidence, and received ample funding for the expanded role which he

played throughout the war.

In May

1940, the

Germans overran Holland and Belgium surrendered, and

the following month, Marshal Pétain signed the surrender of

France.

Tens of thousands of refugees fled over the Pyrenees hoping to cross

Spain to freedom. The Spanish authorities were initially very

accommodating to all except men of military age, but the Vichy

government soon made it difficult to leave France by restricting the

issue of exit visas, and the Spanish refused entry to anyone without

one. In 1941, under pressure from Germany, the Spanish regulations

became progressively more irksome, although they did not distinguish

between Jews and non-Jews, but in the summer of 1942 the Vichy

government cancelled all exit visas for Jews and without them, they

were unable to obtain Spanish transit visas. The result was an increase

in the number of illegal “indocumentados”

throughout 1940

which

accelerated during the subsequent two or three years, and these were

liable to indefinite imprisonment which, in the case of men, usually

meant the harsh conditions of Miranda de Ebro. During the early years,

some refugees were turned back at the border and some were sent back to

France after reaching Barcelona

(14),

but as many as 30,000 Jews may have

escaped through Spain during the first half of the war. Assisting

refugees of all races from Allied, and other, countries, became a major

workload for the British Embassy in Madrid(16),

and the ambassador

estimated that this assistance was extended to over 30,000 refugees

between 1940 and the end of 1944, although somewhat inclined to take

the credit for this humanitarian undertaking himself and remaining

silent concerning the pivotal roles played by Hillgarth and by

Martínez. He also emphasised how very capricious and

unpredictable were

the responses of the Spanish authorities to the presence of these

fugitives within their borders.

The

network of

which Martínez was the chief architect, made

possible

the liberation of personnel from Miranda de Ebro, the avoidance of

incarceration in that establishment in the first place, and exit from

Spain to Portugal. The first of these initiatives he accomplished by

taking advantage of his authority as a Spanish doctor and former

officer in the Nationalist Army. Observing how delighted the commandant

was to get rid of a victim of typhus who was to be admitted to

hospital, Martínez promptly found himself with a major, and

completely

factitious, outbreak of the disease on his hands. Borrowing an

ambulance from a friend and colleague, he certified large numbers of

the prisoners as being infected, and spirited them away from the camp

either to the Embassy, or to Margarita Taylor’s apartment

above

the tea

rooms, or to his own bachelor apartment, where they were concealed,

furnished with money, nourishment, clothing and documents, and driven,

concealed in a car from the Embassy fleet, on the next stage of their

journey to England.

It was

highly

desirable, if at all possible, to circumvent the

hospitality of Miranda de Ebro, and he enabled many of these birds of

passage to achieve this by enlisting the help of his chaplain from

Civil War days, a Capuchin monk who, aided by a couple of his brethren,

provided a safe haven in a little monastery of retreat in Jaca, in the

Pyrenees. Martínez also persuaded some of the country

innkeepers

along

the way, to provide secure shelters for his clients, and a report from

“Doctor Alonzo” [sic] in his SOE file claims that

“The men who enter

through Navarre are well looked after by “SABAS” in

the

Pyrenees. He

picks them up, feeds them at his inn and then takes them down to

Pamplona to his farm…” From here, they would be

driven in

an official

Embassy vehicle – which attracted, but was theoretically

immune

to, the

suspicions of the Guardia Civil patrols – to Aranda de Duero,

between

Zaragoza and Valladolid, and thence to Portugal or to Galicia.

Some of

the

escapees left Spanish soil by reaching Gibraltar and the

relative safety of the Royal Navy. Others were concealed in La Portela,

Martínez’ rambling, well-hidden finca on the shore

of an

inlet 10 km

from Vigo where he had spent many happy family holidays during his

childhood, and where members of his family still lived. Vigo was an

important port, where Hillgarth and, almost certainly,

Martínez,

maintained surveillance over the U-boats and other German shipping

which regularly used it for refuelling and provisioning.

Martínez had

many loyal childhood friends here, and two of these families owned

boats which they used to ferry Martínez’clients

across the

river Miño,

which marks the border with Portugal, to Valença. Transport

to

the

river bank was arranged by Martínez, either through the

Embassy

or

using a trusted friend’s taxi, and he would often accompany

the

fugitives himself on various stages in their hazardous passage across

Spain.

Hasty

departure for the UK

Vigo

was crawling

with German agents, and towards the end of 1941, the

Gestapo began to close in on Martínez’ nefarious

activities. “Through

his activities on our behalf he was eventually brulé and had

to

leave

Spain”, as an internal memorandum puts it, and a later letter

stated “…

as you know [he] did some first rate work body passing in Spain before

he became compromised and was sent to England”, so

arrangements

for his

transfer were made. This did not fit in particularly well with his

plans to be married to Ramona, the daughter of a Galician doctor, in

January 1942, but the marriage went ahead and the imminent departure of

the couple on their travels was understood by their friends and

relatives to be on honeymoon to an unknown destination. After two days

in La Portela, they travelled to Madrid where they stayed a few days in

his little apartment with his consulting room in the Salamanca area.

Martínez was instructed by Hillgarth to obtain passports, a

transaction

which itself would arouse suspicion, were it not for the serendipitous

honeymoon, and to tell Ramona as little as possible for her own

protection. A high-ranking official and irreproachable fascist, a

drinking partner of Ramona’s father, duly obliged with the

passports.

Too late, he discovered that this was more than just a honeymoon:

“They

can never come back”, he told his friend, “if you

want

[Martínez] ever

to leave prison – or worse!(2)”

His attitude seems to have

been

ambivalent, and he later stoutly rebuffed an angry SS officer who

accused him of breaking the Axis “Pact of Steel”.

One

morning, a black

saloon with diplomatic plates and a little Union Jack pennant swept

them off to Ciudad Rodrigo, to the west of Salamanca and near the

Portuguese border where their passports and salvoconductos secured them

an easy transit. From there, they went to a little hotel in Lisbon for

a few days, during the course of which they found themselves being

wined and dined by some very eminent exiles from the Civil War who were

united by only one ideology – the necessity to get rid of

Franco

(who

would outlive them all). And then, one morning brought another official

car, a silent trip to a military airfield in Sintra, a waiting War

Office transport aircraft, and a flight to snowbound Cardiff.

The

Intelligence

Officers at the British Embassy in Madrid, meanwhile,

thoughtfully told the porter of Martínez’

apartment block

that the

doctor and his wife would not be returning since they had been killed

in a motor accident. The Gestapo knew that there had been no accident,

and no bodies, and subjected his nurse, Carmen Zafra, to prolonged

questioning. She had been a loyal friend since Civil War days, and

Martínez had sent her numerous letters at her home in

Barcelona

after

his defection, via an intermediary correspondent in London, a member of

the staff of the Wellcome Foundation(5).

Once

they had

settled in London, there were three main strands in

Martínez’ life. He and Ramona enjoyed a happy, and

busy,

social life,

in spite of the air raids. They were made very welcome, and appear to

have received tickets to plays and concerts from official sources.

Among their friends were many exiles from the Spanish Civil War,

including Juan Negrín, Prime Minister of the Republic, and

Col.

Casado,

the officer who had finally surrendered Madrid. When meeting someone

new, one did not enquire which side they had been on, but it usually

became rapidly apparent. Some idea of Martínez’

views was

revealed in a

form in his SOE file, in which he states “Am very interested

in… a

Spanish Restoration on democratic lines”, which may tell us

more

about

his loyalty to Queen Ena than about his politics. His SOE superior

noted approvingly that “Unlike most other Spaniards arriving

in

this

country he has apparently no Red tendencies”.

Having

qualified in

the UK, there was no problem with registration, and

he worked in a surgical team at Queen Mary’s Hospital,

Roehampton. His

main interest was in thoracic surgery, and he spent a period as Senior

Surgical Assistant to Mr (later Sir) Clement Price Thomas at the

Brompton.

He

continued to

remain in close contact with the Intelligence Service,

the Foreign Office (FO), and Captain Hillgarth and, acting from

humanitarian motives, managed to procure considerable supplies of

vaccines and other medical necessities which they, acting from

political motives, distributed in Spain. “I really believe

this

is one

of the best bits of propaganda we could have done”, a

jubilant FO

contact recorded. Most of his escape routes continued to operate in

Spain without him. He could not be certain, however, that his own

personal involvement in the conflict was over, especially when he

received a visitor one morning who refused to give his name. He did,

however, divulge the information that the Germans had a force of 30

Divisions waiting at the foot of the Pyrenees, ready to march through

Spain, take Gibraltar, and take up position in North Africa –

and

Martínez’ military experience in the Civil War,

together

with his

perfect English and unrivalled knowledge of both countries, would make

him the ideal candidate to be parachuted in (or taken to a Spanish

port) to undertake subversive action behind the lines. He would command

a team of five others, under the name of Lieutenant Marlín.

To

this

proposition Martínez agreed, but only if Franco entered the

war,

and to

this, the FO agreed. The group travelled to a converted farm in

Scotland, by the name of Camus Daruch, for intensive training in the

dark arts of sabotage and unarmed combat, which he did not particularly

enjoy, and for some fairly intensive whiskey-tasting, which he enjoyed

very much. “This student”, the Officer Commanding

reported,

“will

probably prove an extremely useful operative.” Shortly

afterwards,

however, the situation changed, the Divisions were deployed elsewhere,

and his contacts with the FO ceased.

Return

to Madrid

When

Germany

capitulated, Martínez’ first thought was to

return to his

native land, for despite his anglophilia, he was a bon viveur who

missed the red wine, the corrida, flamenco, and grilled sardines(2).

They

waited a few months, with the result that their daughter was born a

British citizen, and returned in 1946. He became Director of Thoracic

Surgery at the San José and Santa Adela charitable Red Cross

Hospital

and visiting consultant at King George V Hospital, Gibraltar (in spite

of the dispute over the sovereignty of the Rock), and performed the

first resections for bronchogenic carcinoma in Spain, as well as

publishing a booklet on thoracic emergencies. He maintained contacts in

the UK, including his friend at the Wellcome as well as another

longstanding acquaintance, Sir Robert Macintosh, who had been appointed

to the first chair in anaesthesia in this country, at Oxford, in 1937,

and who had been invited to San Sebastian during the Civil War to

anaesthetise for an eminent visiting American reconstructive plastic

and maxillo-facial surgeon, Joseph Eastman Sheehan. Martínez

had

met

Macintosh at that time, and on the latter’s occasional

post-WWII

visits

to Madrid, they would spend time together (mainly in restaurants!)(19).

Being bilingual, he was very much in demand from British and American

hotel guests, and his life seems to have enjoyed a well-earned respite

from the turmoil it had been thrown into by the raging political and

military conflicts which blighted the 21st century. He died in 1972,

and although he remained bound by the Official Secrets Act, which he

had signed in 1943(17), and

carried his

secrets with him to the grave, he

had had the satisfaction of receiving an award from the Polish

government in exile for the leading role he had played in the rescue of

at least 200 Polish Jews, and, in 1947, the King’s Medal for

Courage in

the Cause of Freedom. As a telegram from Madrid stated in his file,

“…he is a most valuable man, completely with us,

and…we owe him a great

deal.”

Conclusions

The

tale of Dr

Eduardo Martínez Alonso is told here because he

has

received so little of the acclaim which he deserves in this country,

although his daughter is achieving considerably more recognition for

him in Spain; his memoirs received a favourable, but extraordinarily

unperceptive review in the Lancet. He undoubtedly saved more lives

through his undercover operations than he did through his surgical

operations, although he clearly saved the lives and limbs of many

casualties from the battlefields of the Spanish Civil War. He may be

said to have acted as a doctor in both regards, because he owed his

humanitarian ideals to his profession and to the immense suffering

which he had witnessed. It also needs to be emphasised that not all who

served under Franco were evil, and not all who opposed him were

saintly, in an era in which the Spanish government seems determined to

air-brush the dictator out of history, and in which a strongly

pro-Republic account of the SCW is also purveyed throughout this

country. A concluding observation is, that being bilingual, bicultural,

and fiercely loyal to another nation as well as one’s own,

may

open up

unexpected opportunities to be of service to humanity and may steer

one’s life into uncharted and often choppy waters.

References

1. Martínez Alonso E. Adventures of a Doctor.

London:

Robert Hale, 1962

2. Martínez de Vicente P. Embassy y la

Inteligencia de

Mambrú. Madrid: Velecío, 2003

3. Martínez de Vicente P. Personal Communication,

2009

4. Knoblaugh HE. Correspondent in Spain. London:

Sheen and

Ward, 1937: 85-88

5. Martínez Alonso E. Correspondence 1938: Archive

WA/HMM/CO/Alp/15: Box 69,

Wellcome

Library

6. Thomas H. The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin, (1961)

3rd

edn. 1977: 940

7. Preston P. Franco. London: HarperCollins (1993) Fontana

edn.

1995: 393-400

8. Ibid: 347, 957

9. Smyth D. Diplomacy and Strategy of Survival: British Policy and

Franco’s Spain

1940-

41,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986: 26

10. Payne S.G Franco and Hitler, New Haven: Yale University Press,

2008: 69

11. Smyth D. Op. cit: 28

12. Smyth D. Hillgarth, Alan Hugh (1899-1978), rev. Oxford Dictionary

of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004; online

edition, January 2008

<http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/31233> accessed 9

March

2009

13. Avni H. Spain, the Jews, and Franco, trans. Martíneznuel

Shimoni, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1982:

72-79

14. Ibid: 180

15. Ibid: 91

16. Hoare S.J.G. Ambassador on Special Mission, London: Collins, 1946:

226-238

17. Records of Special Operations Executive, National Archives, Kew,

file HS 9/26/5

18. Alvárez-Sierra J. (ed.) Diccionario de Autoridades

Médicas, Madrid: Editora Nacional, 1963: 317

19 Macintosh R.R. Correspondence 1946: Archive 1946 PP/RRM/C/11,

Wellcome Library, London

20. Book Reviews Lancet 1962; I: 1106

Footnotes

a. Another term used in this context was

“outfiltration”

(although medical readers would undoubtedly favour

“exfiltration”).

b. Urgencias Torácicas, Madrid:

Gráficas Udina, 1959

Legend

to Figure

Figure 1. Eduardo Martínez Alonso in the uniform of a

Capitán Médico in the Nationalist Army]

Once

again The Aliens have come up

trumps, our own Oskar Schindler

|

|

|

|

King

George Medal for Courage

in

the Cause of Freedom

|

Polish

Gold Cross of Merit

|

Eduardo passed away

in Vigo in 1972

Dr

Eduardo Martinez Alonso

(1903-1972)

Dr

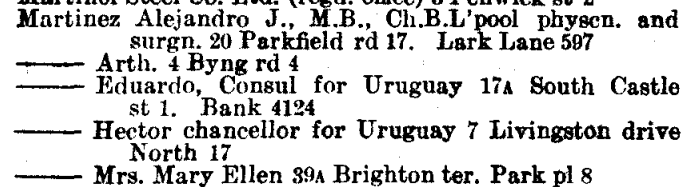

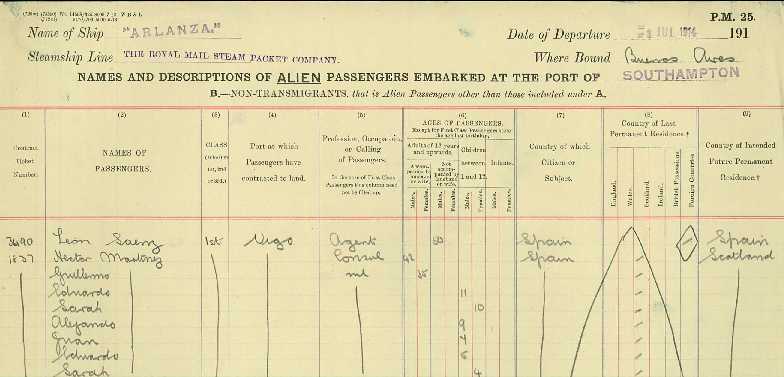

Alejandro Juan Martinez

Born

two years later than Eduardo,

Alejandro followed in his brother's footsteps and qualified as doctor

at Liverpool University. The 1938 register shows he was a G.P in Sefton

Park and his Dad and Uncle were still at the Consul.

He got married in 1937 and at some time after WW2 they moved to London.

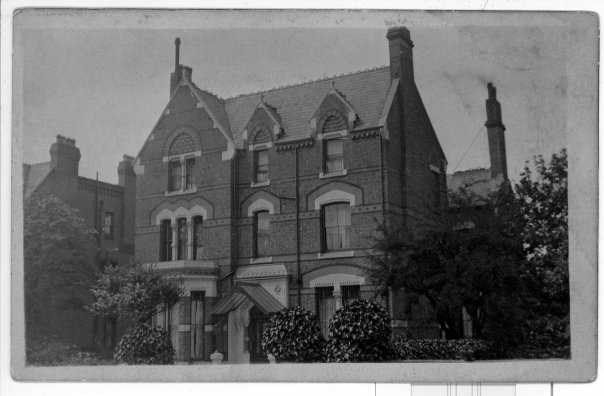

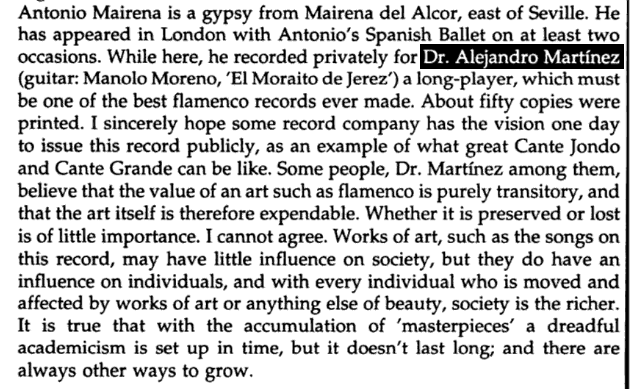

A book entitled "

The Flamencos of

Cádiz Bay"

published by Gerald Howson in 1965 shows how

accommodating the Martinez family in Vigo were.

Alejandro

passed away 1978 in Lambeth,

London

Dr

Alejandro Jaun Martinez

All

Aliens RFC, Seft0n

RUFC

photographs, programmes and memorabilia Copyright © 2012

Sefton RUFC