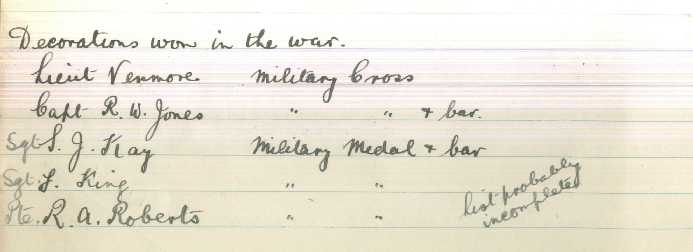

The Rugby Club Doctors

Written and researched by David Bohl, with the kind help and documents supplied by World War 1 historians worldwide.

On either side of the Great War of 1914-18 the rugby club was graced by a number of the medical fraternity, a blend of honorary and playing members complimenting the established teaching profession.

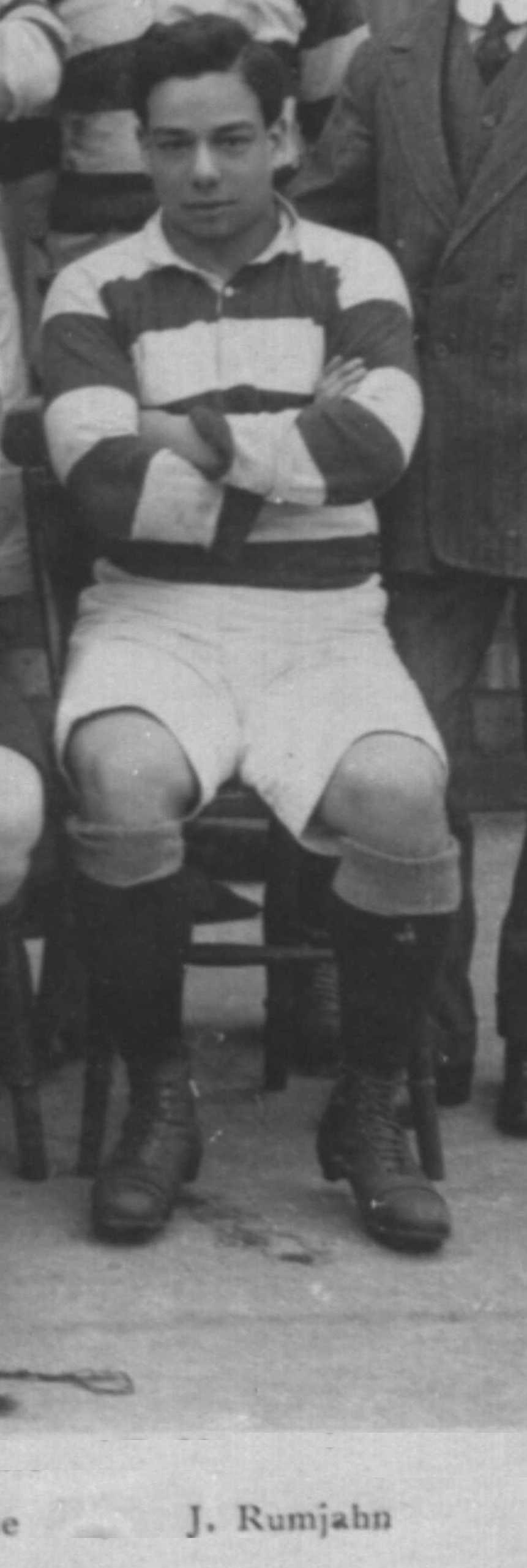

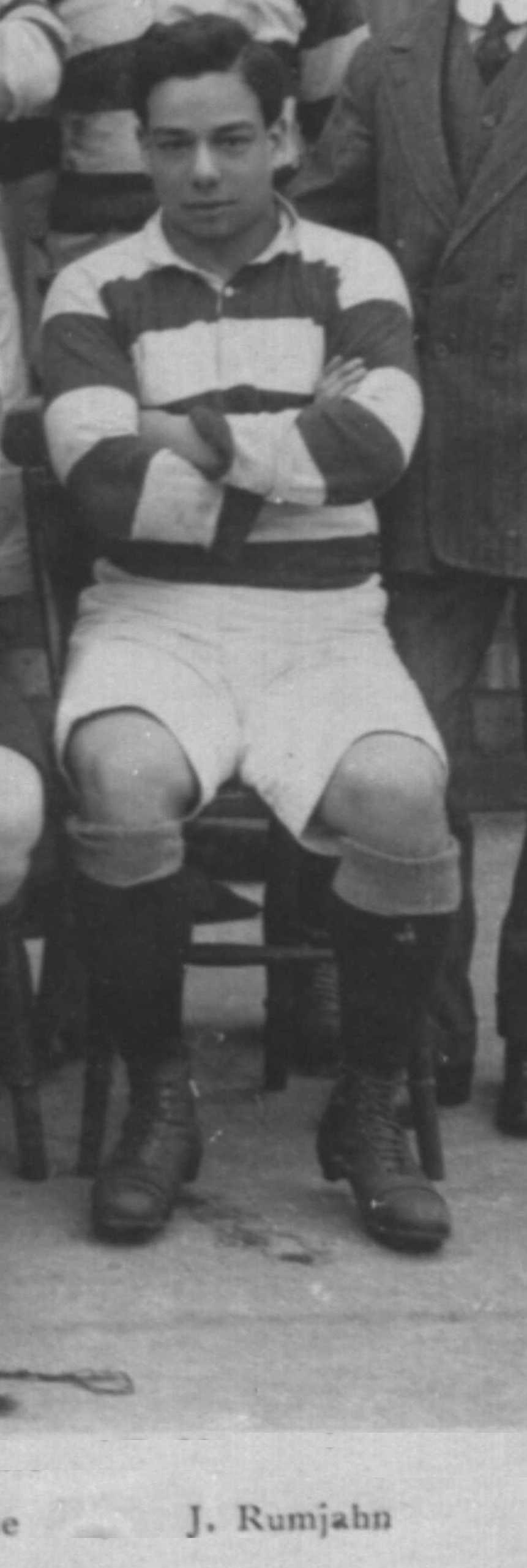

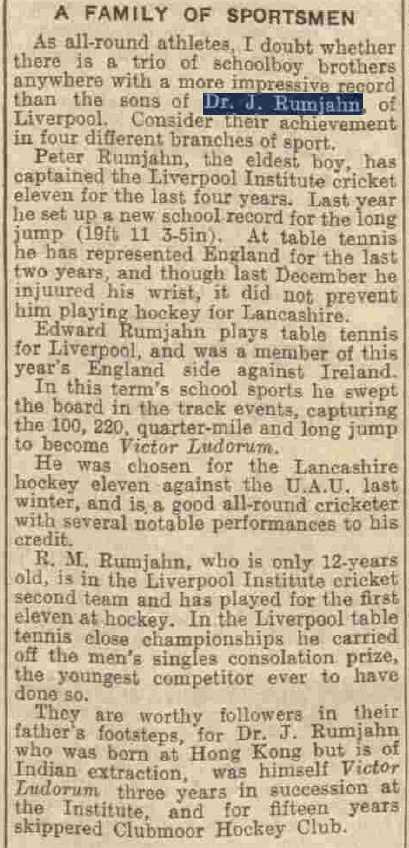

Dr Jaffir Rumjahn

|

|

|

|

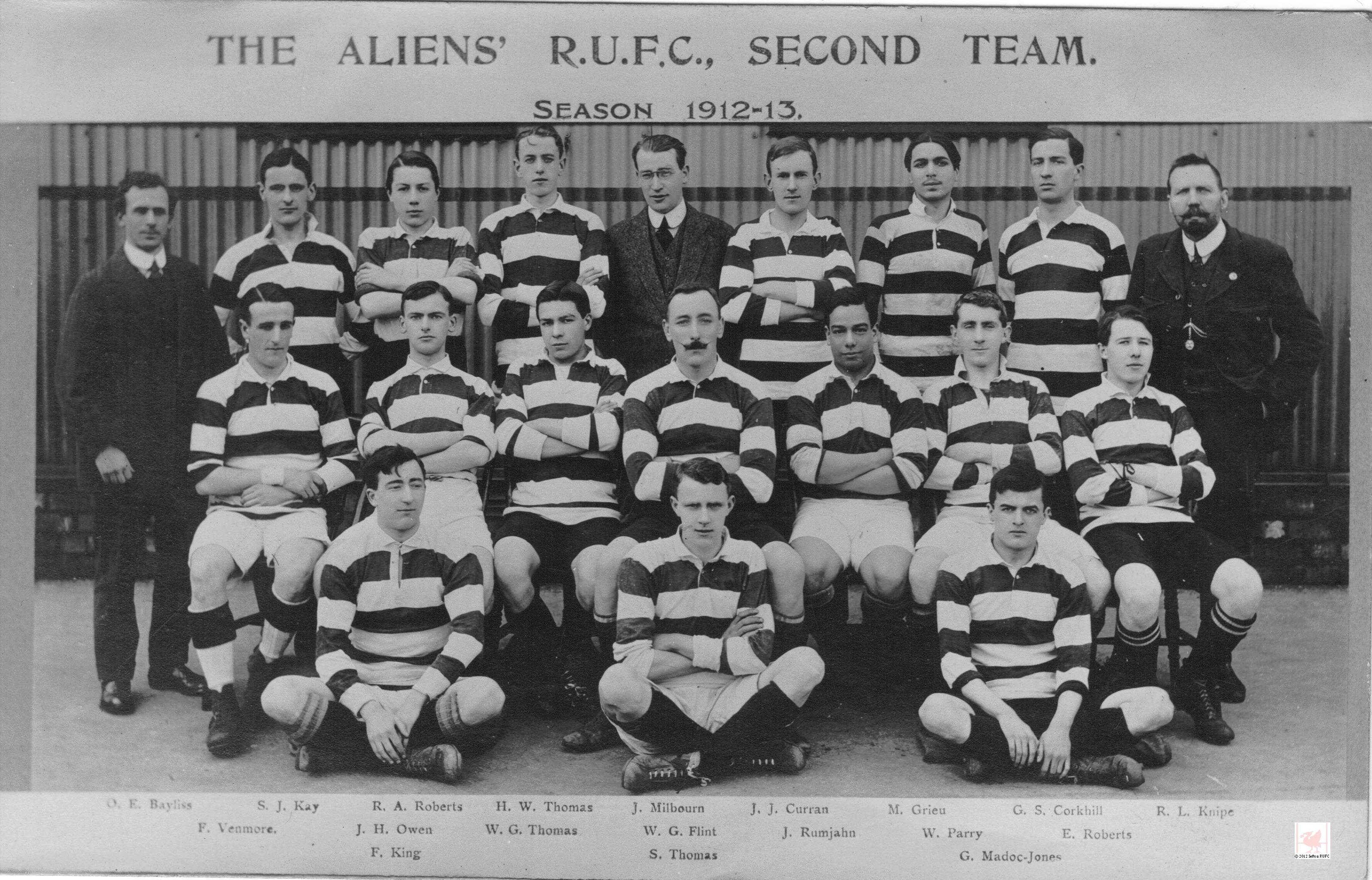

Sefton

1XV 1912-13

|

Clubmoor

CC

|

Hall Marked Gold Medal 1929 |

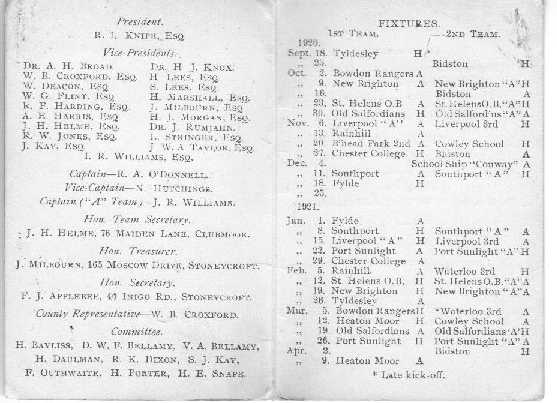

First played for the Aliens on 19th November 1910

ALIENS LOSE TO BARNSLEY.

The Aliens had an attractive tit-bit for their supporters at Clubmoor on Saturday, when they entertained the Yorkshire Cup semi-finalists. Unfortunately, Barnsley were minus several of their regular men, and the Aliens very sportingly lent them a couple to enable them to put a full team in the field.

In the opening half the home team had the greater portion of the attack, but failed at the critical moments, when a cool head would have been invaluable. Their forwards on many occasions made much ground, but as a rule an ill-directed pass or a knock-on brought the movements to an untimely end. Yet they did most of the attacking for their side, and it was the forwards who initiated the movements which resulted in the scoring of their two tries-Bob Jones getting one in each half. The Barnsley forwards were a lusty lot, and played the typical kick-and-rush game in menacing style, although they were not so progressive as their opponents. Kell, at full-back for the visitors played a capital game, and his defence was always sound. Harris and Dickinson were a pair of hard-working forwards. Huggard, however, was the best man on the side, his fielding under extreme difficulties being excellent. Rumjahn was again at back for the Aliens; he fields well and kicks with judgement. Croxford was the best three-quarter on view, and Bayliss and Ellis are a serviceable pair of halves. Forward, Jones, although a little unorthodox perhaps, was easily the best of the home vanguard.

At the interval Aliens deservedly led by a try to nil, scored by Bob Jones after a prolonged spell of attacking by the home team. The second half was pretty even, and Barnsley were lucky to score from a try which to all appearances was offside. Kell scored again for the visitors and converted his own try. Jones again got through for the Aliens and the Rev. J. Nesbitt counted for Barnsley. On the whole, however, the home team were distinctly unlucky to lose, the result being:

Barnsley 11 pts, Aliens 6 pts. The Rev. Mr. Huggard, chairman of the Yorkshire Union, officiated as referee.

Post 31/3/1913

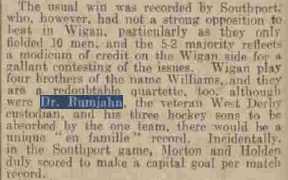

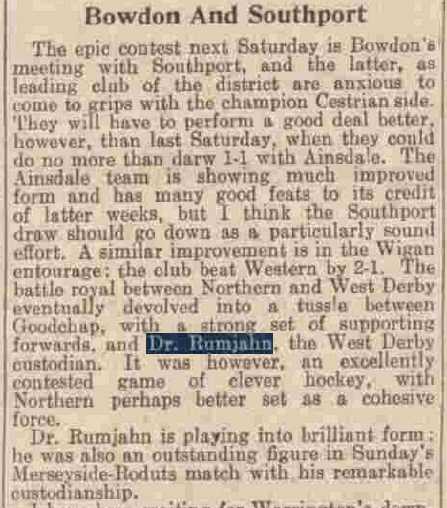

West

Derby Hockey Club

West

Derby Hockey Club

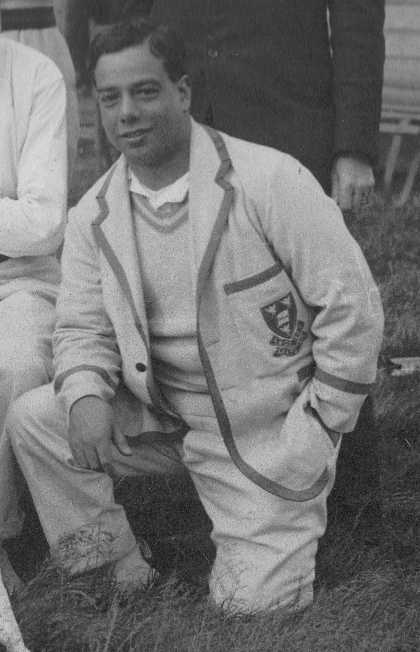

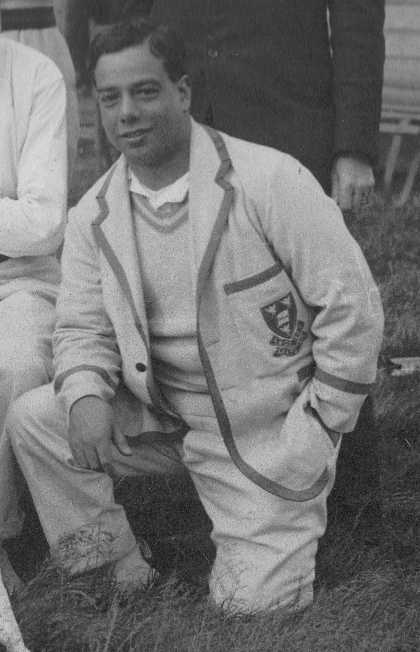

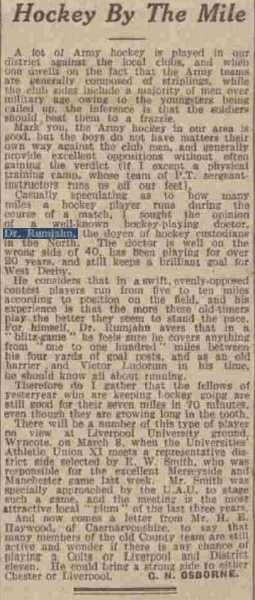

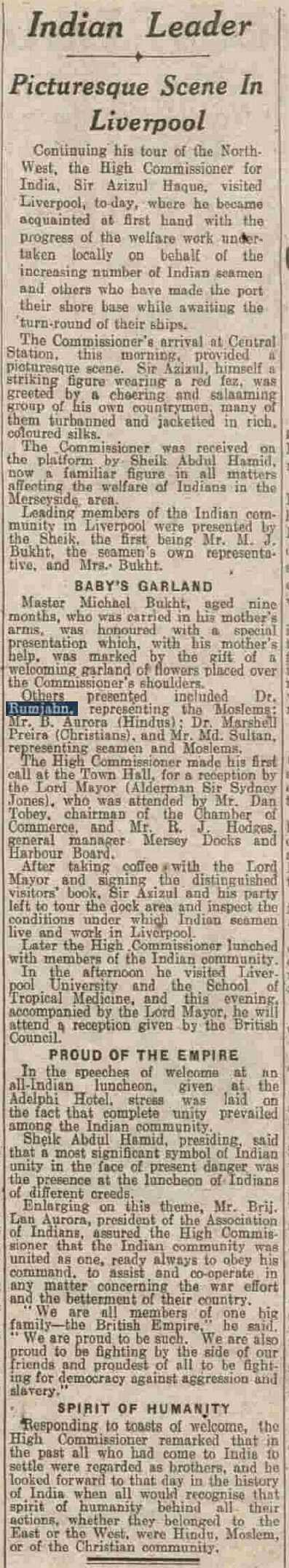

Jaffir was born in Hong Kong on the 8th September 1887 and at aged 14 was sent by his father from Hong Kong to be educated at Liverpool Institute with the express wish that eventually he studied either law or medicine. He qualified as a Doctor at Liverpool University where he was awarded his Blues in a number of sports, having held all kinds of sporting records at the Liverpool Institute, as did his three sons Peter Usuf, Edward Jaffir and Ronald Madar - all of whom were English Internationals at table tennis and County players at hockey. Jaffir played hockey for West Derby where the pitch was next to Sefton (now Harbern Close.) and cricket for Clubmoor CC.

|

|

|

Hockey

1939

|

Tributes

1939

|

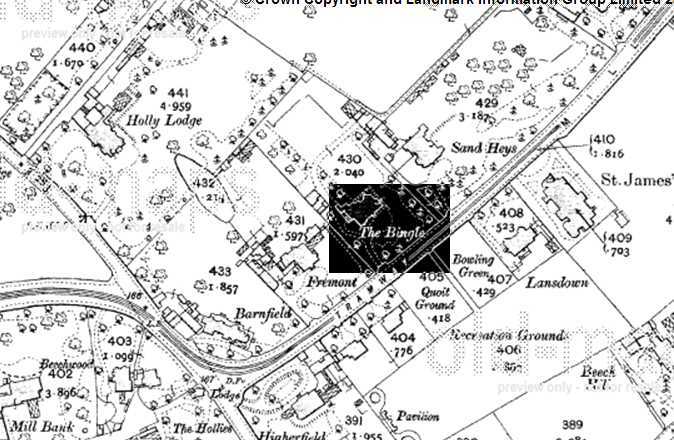

At first he lived at "The Bingle", in Mill Lane (where Holly Lodge netball courts are now) when it was sequestered by the Army, as it had a tower for a lookout. It was hit by a stray bomb in WW2 and had to be demolished. Dr Rumjahn then had his GP practice at 77 Queen's Drive Walton, by Rice Lane flyover and on retirement moved to Huyton. He also had a practice in Roby where the Table Tennis room also served as the Doctor's waiting room! He was GP to our founder member Fred Applebee and his family from Twig Lane, Roby.

[Many thanks to his granddaughter Jan Davies (nee Rumjahn) for the information]

|

|

|

1941

|

High

Commissioner for India 1942

|

Dr Jaffir Rumjahn M.D.

(1887-1961)

Played 1911-14

Elected 25th November 1921

Became Vice-President 13th August 1924

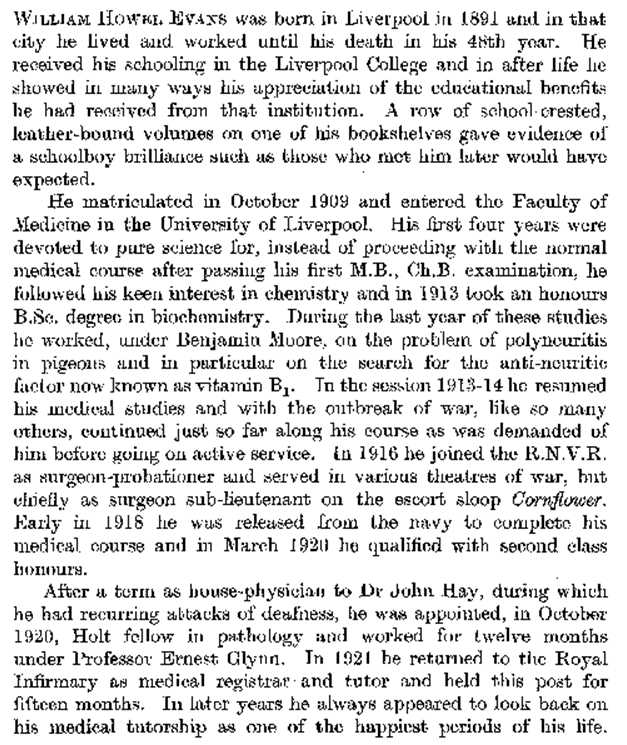

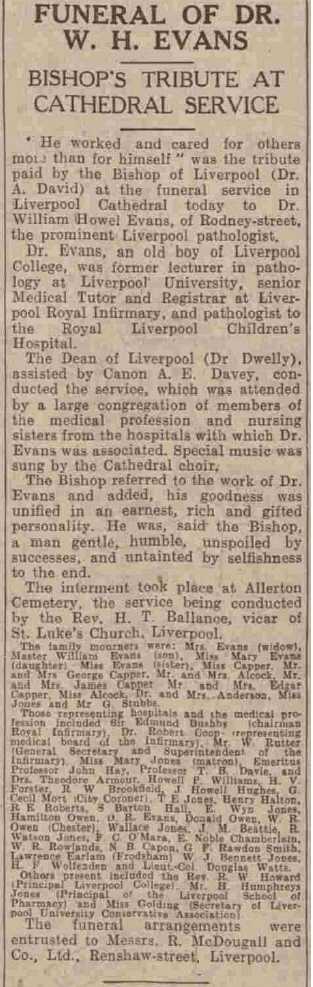

[The Journal of Pathology and BacteriologyVolume 50, Issue 1, pages 177–182, January 1940]

Liverpool Echo 27th October 1911

Aliens 2nd at Clubmoor. This match was remarkable for prolific scoring. The visitors started one short and the homesters pressed their advantage to such good purpose that when half time arrived they led by 32-0. The chief scorer was Helme, who scored five tries of which Flint converted one and Evans two. Half Time 4g 5t

HMS Cornflower was built by Barclay Curle on the Clyde and launched 30th March 1916. She was lost on 19th December 1941 in an air raid at the fall of Hong Kong.

Dr William Howel Evans M.D.

(1891-1939)

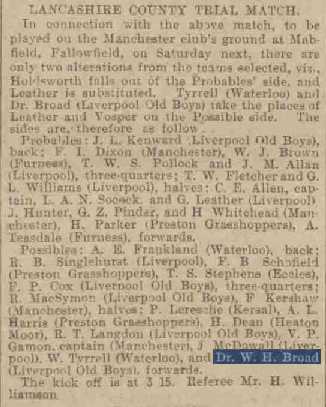

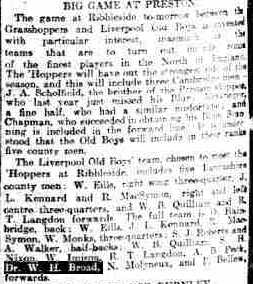

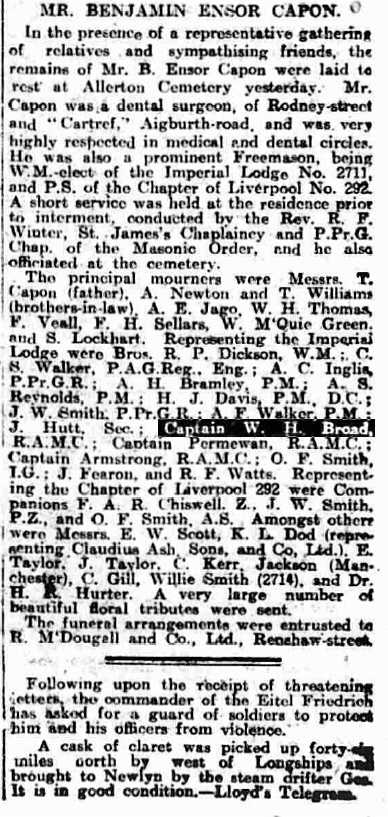

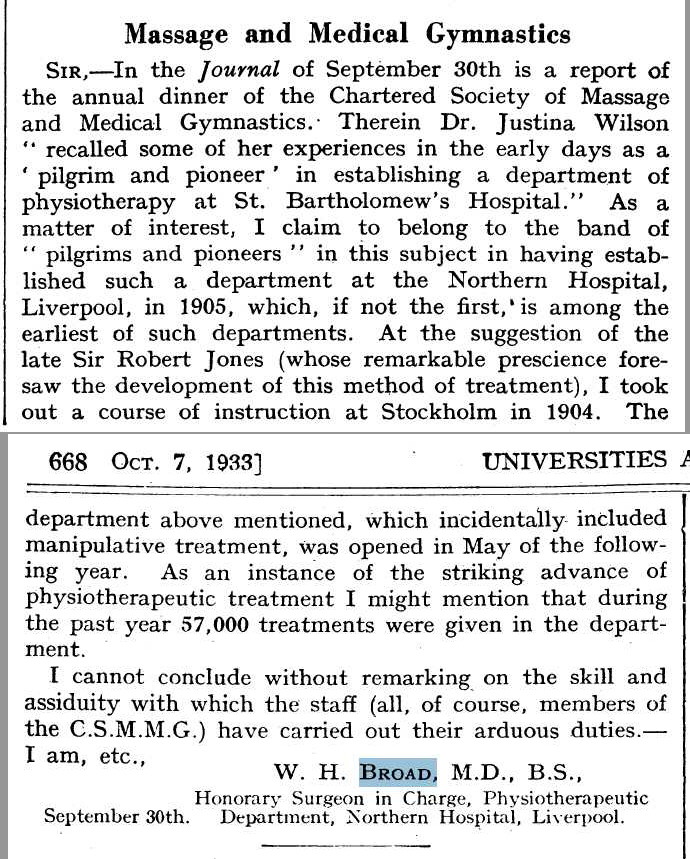

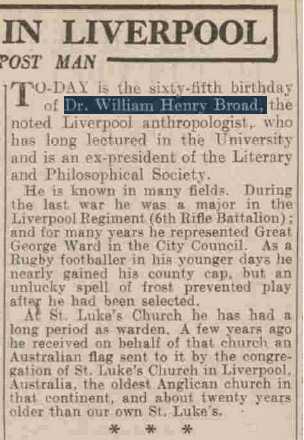

Dr W.H.Broad

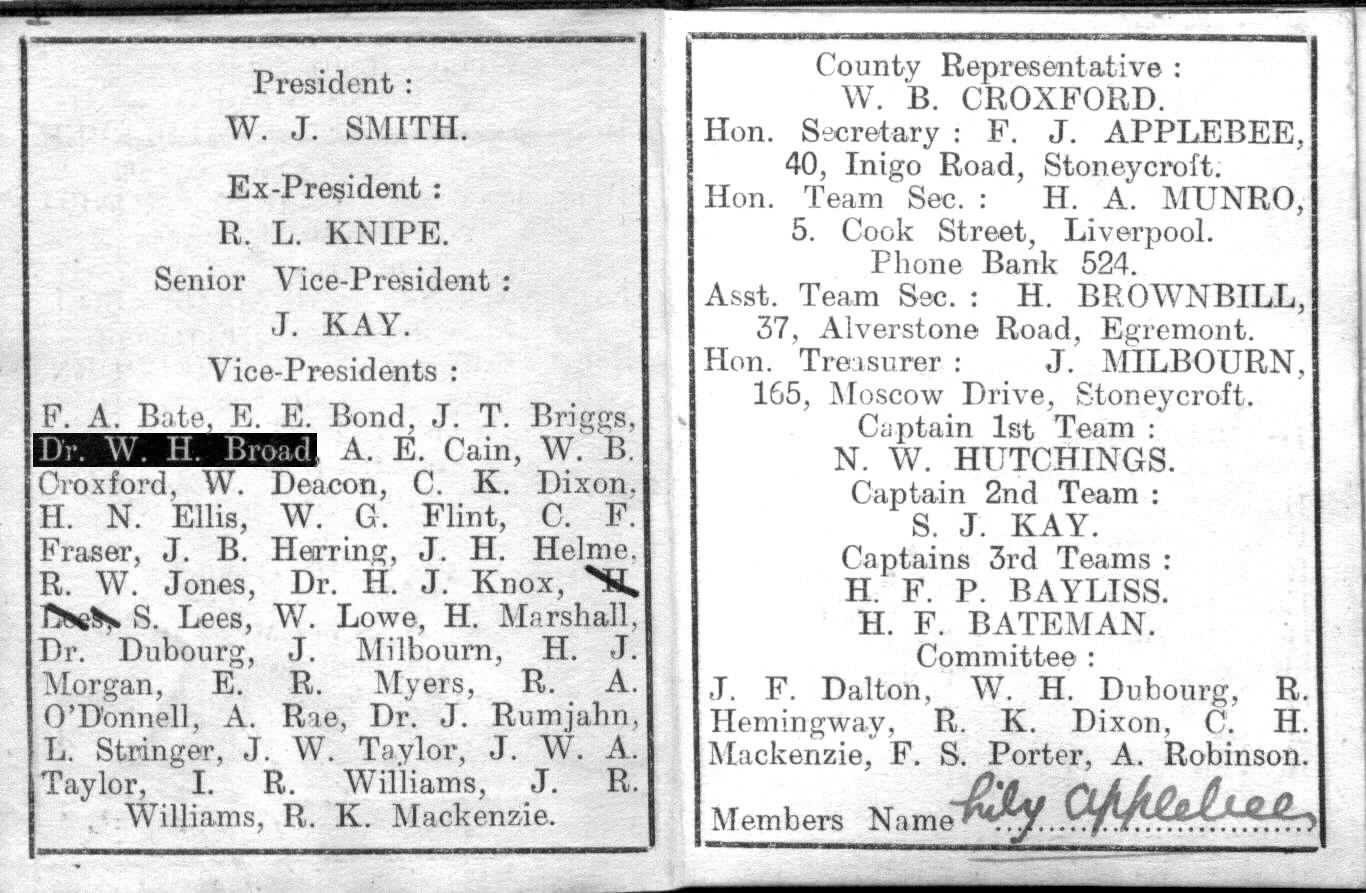

Vice-President August 31st 1920 - 1924

William Henry Broad was born around 1875 in Manchester. After graduating in Liverpool in 1900 he worked in several local hospitals including the Royal Infirmary and became Lecturer in Physical Anthropology at the University of Liverpool.

He played in several games including Lancashire Trials.

|

|

| Manchester Courier 19th October 1906 | Lancashire Post 27th March 1908 |

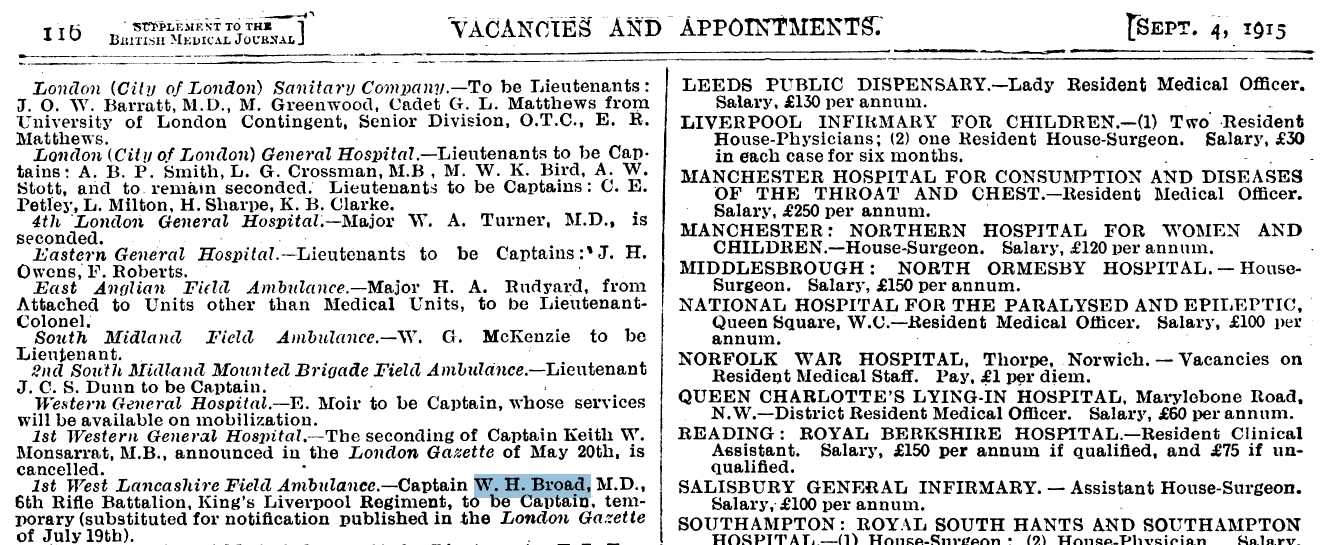

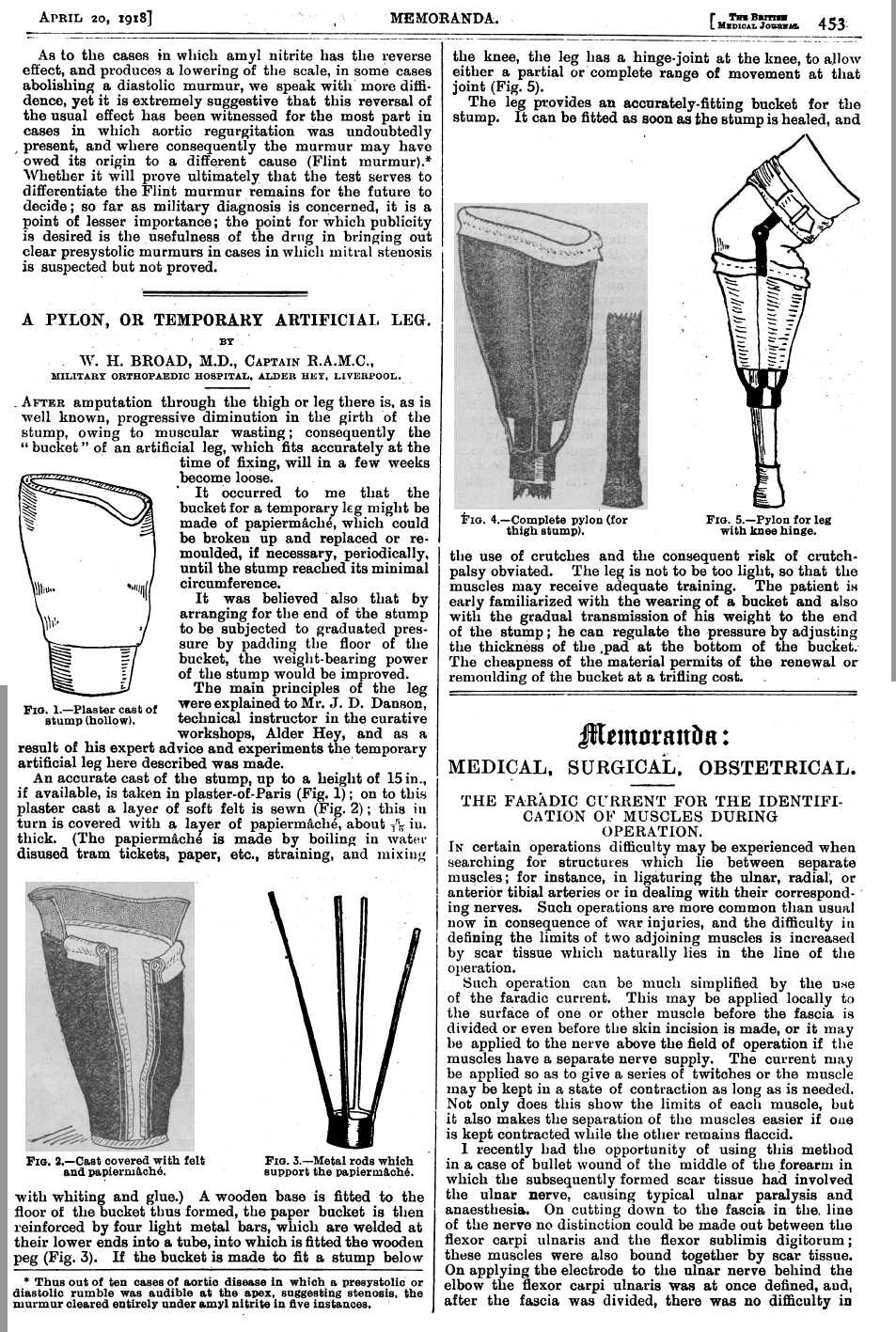

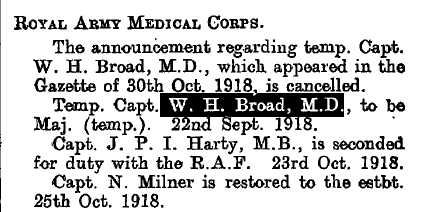

During WW1 he rose to the rank of Temp. Major in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

After the war he worked at Alder Hey Hospital and pioneered the treatment of badly injured soldiers with prosthetic limbs and individually tailored physiotherapy regimes.

An Aboriginal skull obtained and studied by Dr Broad was sold shortly before his death in 1948. It was kept in Liverpool Archives and a few years ago was handed back to the Ngarrindjeri people so that its spirit could continue to the Dreamtime.

LIVERPOOL LITERARY AND PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY.

ORDINARY MEETINGS.

9th December, 1912. The President occupied the chair. On the recommendation of the Council, the Rev. John Sephton, M.A., was unanimously elected an Honorary Member of the Society in recognition of his services, and the long period (46 years) that he had been a member of the Society. The President announced with regret the death of Mr. Joseph Gardner, J.P., a member of the Society. The evening was devoted to short communications. Dr. W. H. Broad giving an interesting account of the difference between the skulls of the lowest type of man and the highest form of ape, and referring to the recent discovery in Sussex of a female skull of very exceptional antiquity.

24th November, 1913. The President (Rev. Dr. Hicks) occupied the chair. Miss Dora McKae Window was duly elected a member, and introduced by the President to the meeting. Dr. William H. Broad, M.D., B.S., Lecturer on Physical Anthropology, University of Liverpool, then read a paper entitled "Pre-historic Man, in the light of recent Discoveries," illustrating this important subject by a number of casts of skulls, as well as drawings and diagrams.

1915

SURGICAL APPLIANCES.

In October, 1917, as a result of the collaboration of Captain W.H. Broad, R.A.M.C. (T.F.), officer in charge of the Massage and Physical Education Departments, and Mr. J.D. Danson, technical instructor in charge of the Curative Workships, a temporary artificial leg was designed. This leg, known as the "Broad-Danson Pylon," had for its objects:- 1. The provision of a light support to enable the patient to dispense with crutches as early as possible, thereby obviating the danger of crutch paralysis. 2. To assist in the shrinkage of the stump. 3. To provide a light bucket capable of being repacked or remoulded at a nominal cost to compensate for the shrinkage of stump. The approval of Major-General Sir Robert Jones, C.B., inspector of Special Military Hospitals, having been obtained, the patients were trained in the making of these limbs. From October, 1917, to November, 1918, 442 of these fittings were made, when, owing to a great demand for same, it was found necessary to make other arrangements. The British Red Cross Society, The Order of St. John of Jerusalem in England, and the Ministry of Pensions arranged for a supply of provisional limbs at various depots throughout the country. The depot at Alder Hey was placed in charge of a provisional limbs committee, which consist of the following gentlemen: Lieut.-Colonel MacDiarmid, O.B.E., R.A.M.C., officer commanding Alder Hey; Capt. A.P. Hope Simpson, officer in charge Curative Workshop; H.C.R. Sievwright, Esq.; the late G.H. Corbett-Lowe, hon. secretary, Liverpool Branch, B.R.C.S.; and Capt. H.P. Mounsey, auditor. In November, 1918, a number of Red Cross workers were engaged, and under the supervision of Mr. J.D. Danson, their training in the manufacture of provisional limbs was commenced, and up to the present 782 fittings have been produced, making a total of fittings supplied to limbless men of 1,224. In addition to the provision of pylons, special feet and chapart fittings are supplied at this depot. Much of the success of the work carried out by this committee was due to the untiring efforts of the late Mr. G.H. Corbett-Lowe, and his assistance and advice will be greatly missed by the members of the committee. The depot is represented on the Headquarters Committee Provisional Limbs Department, 83, Pall Mall, London, by Lieut.-Colonel MacDiarmid, whose interest in the work is very keen.

[www.merseysiderollofhonour.co.uk/partinthewar]

Alder Hey Hospital Orthopaedic Hospital

A military unit treated cases not sent to the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital (London) from March 1915 onward. In addition a special 200 bed unit for limbless men domiciled in Cheshire and Lancashire, excluding Manchester, was established at Alder Hey.

[www.1914-1918.net/hospitals_uk]

[British Medical Journal]

Medical services. Surgery of the war (Volume 2) by William Grant Macpherson.

At the Liverpool Pensions Hospital Major W. H. Broad, the officer-in-charge, made a practice of seeing each patient in the presence of the gymnastic instructor, to whom he gave detailed instructions as to the treatment. This is a very important matter. Patients should never be passed on to a lay gymnast, however clever he may be, with a bare request for " exercises." Patients who were capable of participation in a general class did individual exercises suited to their special disabilities before joining it each day. It was noted here that a routine of " drill " exercises without the variation of games soon palled, and many varieties were introduced, the most popular being " basket ball." Major Broad mentions the case of a patient who had his internal semilunar cartilage excised. Five days after the operation massage was begun ; ten days later, gentle movements ; on the fourteenth day he began treatment in the gymnasium, and on the twenty-first day after the operation he jumped 4 ft. 10 in. high, taking off with the injured leg.

[www.ebooksread.com]

Dr W.H.Broad and Everton FC

The minutes of Everton FC on the 18th February 1919 record a report being read out from Dr W.H.Broad regarding an injured player J.Miller. He was examined and would be fit for duty on the 22nd.

General Meeting held at Bee Hotel August 31st 1920

The Election of officers resulted as follows.

|

President. |

R.L.Knipe |

|

Vice-presidents messrs |

W.B.Croxford, R.F.Harding, R.W.Jones, J.Kay, H.Marshall, J.Milbourn, H.J.Morgan, L.Stringer, J.W.A.Taylor, I.R.Williams, W.G.Flint, A.E.Harris, Dr W.H.Broad, Dr Rumjahn, J.H.Helme, W.Deacon, S.Lees, H.Lees and Dr H.J.Knox. |

Around 1920 Major Broad was awarded the Territorial Decoration (T.D.) This is granted for a minimum of 20 years commissioned service, with service in the ranks counting half and war service counting double.

|

|

|

|

|

Liverpool King's Regiment |

Royal Army Medical Corps |

Territorial Decoration |

Dr W.H.Broad and the Aboringinal Skull

Lynne Heidi Stumpe explains…

Ok, well today I’d like to tell you a little bit about the background to the Australian skull that went back to Australia earlier this year. We actually received the request to return in December 2005, a number of years ago which gives you an idea of how long it can take to complete the repatriation process.

The request came in December 2005 from somebody called Bernie Yates, who was speaking on behalf of the Australian government. Bernie was working in the office of Indigenous Policy Coordination in Australia at the time and he requested the return of all of the Australian human remains in National Museums Liverpool’s collections. These were actually just the remains of three individuals and one of these individuals was represented by a skull with a separate jaw bone.

As some of you know, you may have been here actually, the skull went back to Australia earlier this year and on the 13 May 2009. A ceremony was held at the front of World Museum to mark the handover of the skull to the Australian government representatives and the Australian Aboriginal representatives. But before the actual handover went ahead, there were actually a series of events that were happening behind the scenes.

This is at the museum store in Bootle (shows slide.) This is the human remains cabinet where the skull was kept while it was staying here. One of two human remains cabinets that we have which are usually kept locked. The skull when it was taken out of the cabinet, first thing that morning was very carefully packed into its box, its archive box for transport by Tracey Seddon who’s one of our senior organics conservators. The delegation that came to collect the skull had actually asked us to present the skull covered so it wasn’t being treated in a disrespectful way when it was being handed over to them.

The skull actually was sitting on this little platform here (refers to image); it had its own mount before it was put away. Here are the representatives and the delegation. On the left is Alessandra Pretto, who is the Executive Officer for repatriation from the Australian High Commission in London. The person in the middle is Major Sumner and the person on the right is George Trevorrow.

George and Major are representatives of the Ngarrindjeri people and they are elders, Ngarrindjeri elders. They are wearing paint because they performed a private ceremony at the museum store before the official handover, this was just the two of them on their own in the museum store and they performed a smoking ceremony to cleanse the area that the skull had been kept in, for the sake of the skull itself and the sake of the other items in store around it and after they’d done that we then signed all of the paperwork. There were a number of forms and things to complete and we did all of that after the private ceremony. The actual signing of the forms marked the formal handover of the skull to the representatives who had come to collect it.

So after that the box that the transport crew packed the archive box in to was strapped securely into the van that had been organised by the Australian High Commission and away it went down here to World Museum.

When it arrived you can see that George is holding it, holding the packing crate covered by the Australian National flag and Major kindled a fire in a traditional bark container and put it on the floor. This kind of container is known by a number of different names depending on which language group you’re talking about in Australia, of which there are many. I’m not sure of the Ngarrindjeri name, I’m afraid I forgot to check with George and Major, elsewhere it’s known as a 'coolamon' or a 'pitchi' or a number of different names. The contents of the bowl are smouldering Eucalyptus leaves and a type of sea daisy that comes from the coastal area which is part of Ngarrindjeri territory.

After this, Major then addressed the spirits in the Ngarrindjeri language and he danced with three ceremonial boomerangs and he did this in a particular way - striking each boomerang to the floor and then holding it up to the air. As well as speaking in Ngarrindjeri, he spoke in English about ancestors and about the importance of ancestors and what an emotional moment this was for the Ngarrindjeri to have the skull repatriated to Australia. He thought it was quite interesting that the place opposite to the World Museum entrance, St John’s Gardens, was at one time a graveyard as well. He thought that that might be important to the fact that the ceremony was held in the place that it was.

After this Major performed a dance and cleansed the area again using the smoke and a feather which is a Pelican feather. During this time George also spoke to the audience and Major walked around the circle holding the bowl and fanning the smoke again with the feather.

Finally the crate was packed into its travelling van yet again and after everything was finished that day it travelled down to London for its flight to Adelaide. It was then to travel by road after that to Canberra and to the National Museum of Australia.

So after this you’re probably wondering as I was from the beginning of all of this, how did the skull get to Liverpool in the first place and why was it brought here? Well this is a bit of a detective story and as in all detective stories we’re trying to reconstruct what actually happened from evidence using a variety of different sources, and in this case the original sources are the original documents, the background information and historical information that we can find out and also scientific study; a forensic scientific study of the skull itself.

So in terms of where I came into this, finding out about the skull I looked immediately at what written evidence we had associated with the skull within the museum, but unfortunately this was very very minimal to the extent of things like information written on labels. I don’t know if you can see that very well, I do have those labels here and I can read you out the information. On one side we have the museum number assigned to the skull which is 48-4, which is on both labels, one for the cranium and one for the jaw bone 48-4 Australia.

On the other side we have Aboriginal skull or rather Aborigine skull and on the other label Mandible (skull separate). The skull also had the following written on it in ink which I’m going to read out, I’m not going to show you a photograph of the skull because generally speaking it’s not considered respectful to the skull to show photographs of it particularly now it’s been repatriated. So the skull had the following written on it in ink 48-4 again which is the museum accession number Australian Aborigine and WHB. The initials WHB and these were in a different handwriting which is presumably the handwriting of the donor as we’ll find out shortly.

When the museum acquired the skull it was recorded in the acquisitions register, which is also known as the stock book, and this gives usually minimal details of the item that we’ve acquired and who we acquired it from. Sometimes it gives more information but in this case it didn’t of course. So we had the entry right at the very top which reads 13.2.48; the day it came in, the accession number; 48-4, department; ethnology vertebrate zoology, skull of Australian Aborigine, number of specimens; one and source; Doctor W.H.Broad, 17 Rodney Street, Liverpool . And it was a purchase at the value of eight pounds. The skull is also mentioned in the museums 1948 annual report as a purchase in the Ethnology Collections but with no other details and there is no information on file at all apart from this to say where the skull came from originally or how Doctor Broad acquired it.

So to find out more I had to explore three different avenues of enquiry. First of all Doctor Broad and his history, secondly, what was happening in Australia in the first half of the twentieth century leading up to the skull coming here and thirdly, what the osteological evidence might have to say about it.

So Doctor Broad. Well from sources such as Who Was Who? and his obituary in the Lancet, I found out that William Henry Broad was born in 1875 and died in 1948 shortly after he sold the skull to the museum. He graduated in Liverpool in 1900 and he worked in several local hospitals including the Royal Infirmary. This is an entry in a book called 'Liverpool and Birkenhead in the Twentieth Century' which was published in 1911 and it gives us a nice photograph of Broad himself.

So reconstructing all of this information we found out that between 1902 and 1904, he spent two years travelling, visiting the United States, Canada, Australia and South Africa. On his return to Liverpool in 1904, he became a consultant and he married Cynthia Hawkes, who interestingly was the daughter of Henry Morgan Hawkes of Adelaide in South Australia and they had one son. Doctor Broad was quite well known at that time in Liverpool as an orthopaedic surgeon but also as an Anthropologist. He held a number of prominent positions in the area including Regional Consulting Advisor in Physical Medicine and lecturer in Physical Anthropology at Liverpool University. Anthropology was a kind of second career for him and he was a fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute. He was also a member of Liverpool City Council and a President of Liverpool Literary and Philosophical Society. His publications in scientific and medical journals included the papers, ‘The Skeleton of a Native Australian’, published in 1902 and ‘Prehistoric Man In The Light of Recent Discoveries’, published in 1914.

The first thing that came to mind was could the skull be from the skeleton that Broad had published information about in 1902? Well this is the first sheet of the paper, quite technical as you can see with measurements and so on and information about different vertebrae and he gave quite a lot of measurements about the skull and indeed he described the shape of the skull in his paper. He didn’t give a photograph but from the measurements of the skull in the paper, it didn’t tally with the one that we were concerned with. However, his obituary in the Lancet mentioned another paper entitled ‘Heredity and Skull Form’ published in 1913. Unfortunately this was the one thing that I haven’t been able to find to date, despite searching all the copies of all the relevant journals that it might’ve been published in. The Lancet didn’t mention the name of the journal unfortunately and searching all of the unpublished papers that I can lay my hands on that might be the one were talking about I’ve drawn a complete blank. Of course I’ve contacted Liverpool University over this; I was working with someone there who I’ll mention later. And I also did a little bit of genealogical research and contacted everybody in the local are with the surname Broad, but again I drew a complete blank. I didn’t get to interview anybody in this particular case, unfortunately. It’s possible of course that further genealogical research will turn up something relevant but at that particular point in the research, I didn’t have the time to do it. So I had to abandon that particular line of enquiry at that point.

So another line of enquiry was what might have been happening in Australia at the time of Broad’s visit and what he might have been doing there. For this I looked for published sources including general histories, I looked at scientific journals and I also looked at newspaper articles at the time. And, very interesting story this, apparently sending human remains to institutions outside Australia was very common up to 1913. In 1913, there was a permit system introduced which regulated and controlled the number of human remains being sent out of the country, but before that date it was very very common and in the early 19th century and early 1900’s there were several people associated with medical establishments in Adelaide who were sending Aboriginal remains to the United Kingdom. There were three of these main ones; the first and most famous was someone called William Ramsay Smith who was chairman of the Central Board of Health, city coroner, inspector of anatomy and a doctor at the Adelaide hospital. The second one was Edward Stirling who was the director of Adelaide museum and he was also a professor of physiology at the University of Adelaide. So he had a foot in both camps with collecting for museums and collecting for medical reasons. The third one was Archibald Watson who was Elder Professor of anatomy also at the University of Adelaide. Ramsay Smith was by far and away the most prolific. By the early 1900s, he actually had a supply network of people across Australia and he also acquired remains from the mortuary at Adelaide hospital. This became public knowledge in 1903 and he was at that point suspended from civic and medical duties on a charge of misusing human bodies; however he was later cleared and actually commended for his work.

In general, most of the people supplying remains were members of the medical profession or they had an interest in anthropology or both and the appeared to be collecting for science rather than for overt economic gain. They obtained remains from a variety of sources including Aboriginal burial sites, hospitals that we’ve mentioned and also battlefields and sites of altercation.

At the end of the 19th century, Aboriginal Australians were thought to be becoming extinct, particularly Tasmanians as we probably know. This meant that the skeletons and other remains were in great demand in British scientific circles. Their possession and the related study meant high levels of prestige for an institution and an individual at this time. Ramsay Smith’s UK contacts were mainly with Edinburgh University. Watson and Stirling had contacts elsewhere, but none of the three had any links with Liverpool or Doctor Broad that I have been able to establish.

I’ll just put this (slide) back to Major, a lot nicer to look at than the front page of a journal.

So where does Dr. Broad fit in to this? Well that he wrote a paper on an Aboriginal Australian skeleton in 1902, before visiting Australia, shows that he was keenly interested in skeletal remains of this type. He already had an interest before he went. While in Australia, although he was only relatively newly graduated his aspirations as well as his medical background might also indicate contact with Ramsay Smith and others who were prominent members of the local community at the time. Then Broad’s wife came from Adelaide and in fact the local newspaper the Adelaide Advertiser has social columns with her name mentioned quite often at this period. It is possible therefore that he visited that area while he was in Australia during 1902 to 1904 when he was in his late twenties. Journeying by sea, he would have been there in the middle of his trip in about 1903.

So there are three possibilities for the source of the skull: First of all that Broad may have acquired it before 1902 from Watson or Stirling or Ramsay Smith or from another source in the United Kingdom for example the Anthropology Society of London or auction houses at this time were selling or otherwise disseminating this kind of material. Secondly he may have acquired it in Australia between 1902 and 1904 from Ramsay Smith or other contacts in Adelaide or from another source and thirdly he may have acquired it after 1904, from Ramsay Smith or others in Adelaide or from another source.

So now the skull is back in Australia, it is hoped that further research there might shed some light on this. It is easier of course to carry out that kind of research there than here. I have contacted the museum in Adelaide and other obvious sources of information but without success.

I need to backtrack a little bit, to the identification and attributions from osteological sources. To return to the skull itself. Is there any scientific evidence that the skull is what it says it is, Aboriginal Australian or to show where in Australia it might’ve come from? Well the skull was examined in the first instance by Robert Connolly at the University of Liverpool department of human anatomy in June 2006, but the results were relatively inconclusive.

So through my contacts with the Australian High Commission in London, we arranged with Tania Kausmally, a Research Osteologist based at the Museum of London to examine the skull. This was in November 2006. She identified the skull as an adult female, probably not more than 35 years old. Her report was then passed to Richard Wright, who is the Professor of Anthropology at the University of Sydney, who analysed the photographs of the skull, the tooth size and the measurements. And from the photographs and illustrations provided with the report, Wright identified three features of the skull which indicated mixed Australian and European Ancestry. From analysis of the measurements he used CRANID an acronym which I forget what it means but is the computer program package which compared twenty nine measurements from the cranium with sixty four samples from around the world that included 2870 crania at the time. As there is a high correlation between the shapes of the skulls and the geographical origin of skulls this means that the origins can be kind of inferred from that and mapped out.

The analysis by CRANID also indicated mixed ancestry as did measurements from four of the teeth. This is because European teeth tend to be smaller than those of Aboriginal Australians. Wright also confirmed the skull as female from the CRANID analysis.

So back in Liverpool Museum, trying to put all of this evidence together, when the research had been taken as far as it could go, I provided all of the relevant information in the form of a report in April 2007 to an internal museum committee which included representatives from the Board of Trustees. This report included information on the remains of all the three individuals requested for return. So as well as researching the skull, I was also researching the other remains as well which was again quite a long journey. All of this was done in line with the museums human remains policy which was in place by that time and from all of this it was recommended that all three individuals be returned to Australia. The skull is the first of the three to have had arrangements made for its return. During this the representatives of the Ngarrindjeri people worked with the Australian high commission to organise the travel details.

The territory of the Ngarrindjeri people covers the lower Murray River area near Adelaide, east of Adelaide and the coastal area south of Adelaide. For many generations interestingly, there has been a lot of inter marriage in this area with white settlers. It is possible therefore that the skull originated there. However the Ngarrindjeri people on this trip were specifically collecting unprovenanced, unattributed remains were area of origin is not yet known. The overall idea being that the remains of each tribal group will travel back to their homeland together so that each group will take back their ancestors’ remains.

So that is as far as I can go in this story, but fortunately we do have a film of what happened to the remains that went back to Australia on this particular collecting trip not just the skull from Liverpool but the remains from other institutions as well. All of this process was documented by Maria Meriweather who was introduced to you earlier. So now we’re going to see the film that she made about the return of the remains

[www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk]

1940

Dr Broad passed away in Liverpool 1948

Major William Henry Broad M.D B.S.

(1875-1948)

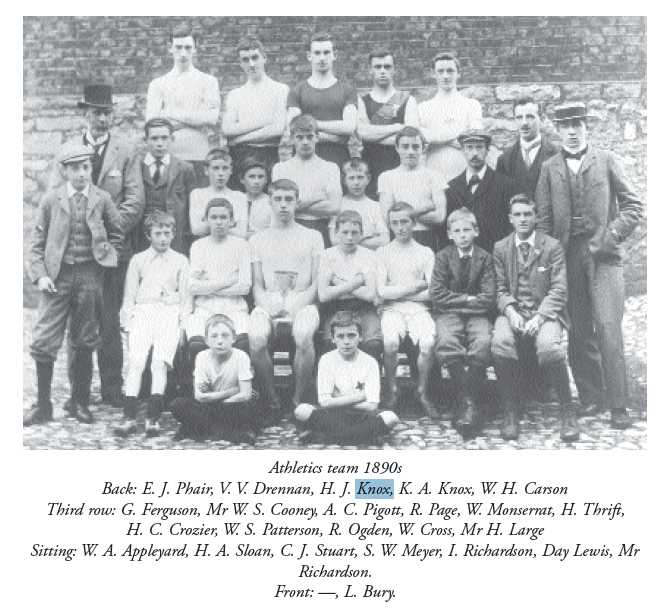

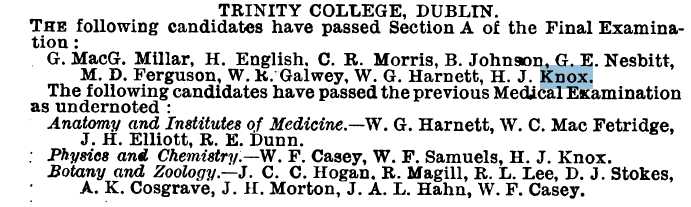

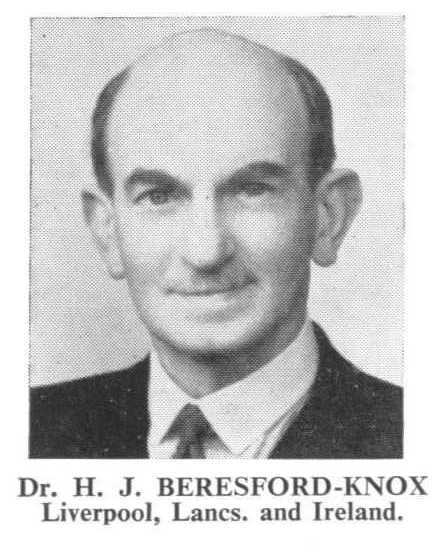

Dr H.J.Knox

Hercules John Beresford Knox was born on 2nd August 1880 at Gortnor Abbey, Mayo in Ireland.

A gifted sportsman at Dublin School he went on to play ten Test Matches for Ireland from 1904-08.

[Photo courtesy of Dublin High School]

Dublin High School - H. J. Knox (1893-96) (Dublin University and Lansdowne)

He graduated with a Bachelor of Obstretic Arts (B.A.O.), Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) and Bachelor of Surgery (B.Ch.).

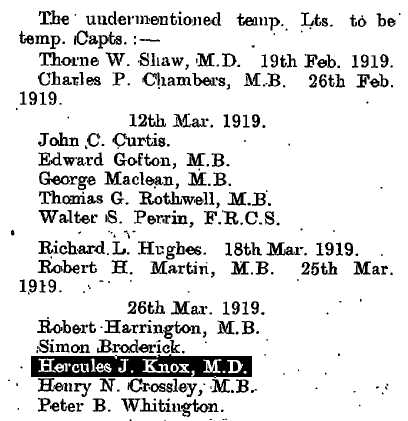

He married in June 1912, having a daughter Aileen Hilary Beresford-Knox, and after WW1 was promoted to Temp. Captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

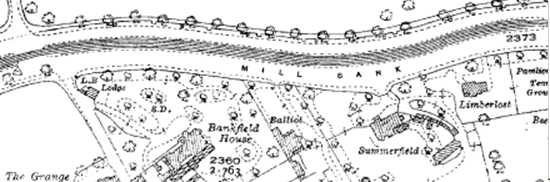

Whilst on Merseyside he played for Liverpool Rugby Club (noted by Liverpool St Helens RFC). His surgery was at Balliol on Mill Bank, West Derby and he practiced in Rodney St.

[www.old-maps.co.uk]

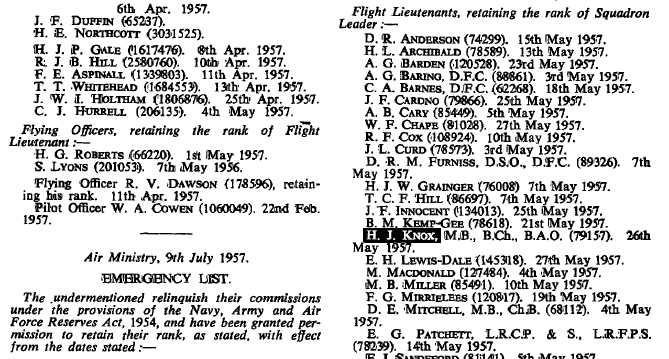

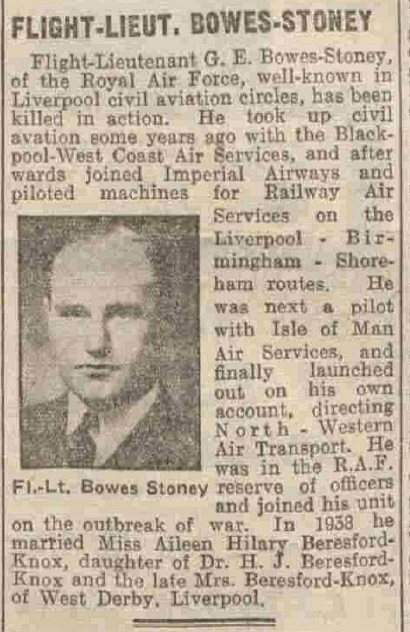

Squadron Leader in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

Daughter takes ill in 1939

Son-in-Law killed during RAF operation 1940

Dr Knox passed away in Liverpool 1975

Dr Hercules John Knox B.A.O. M.D. B.Ch.

(1881-1975)

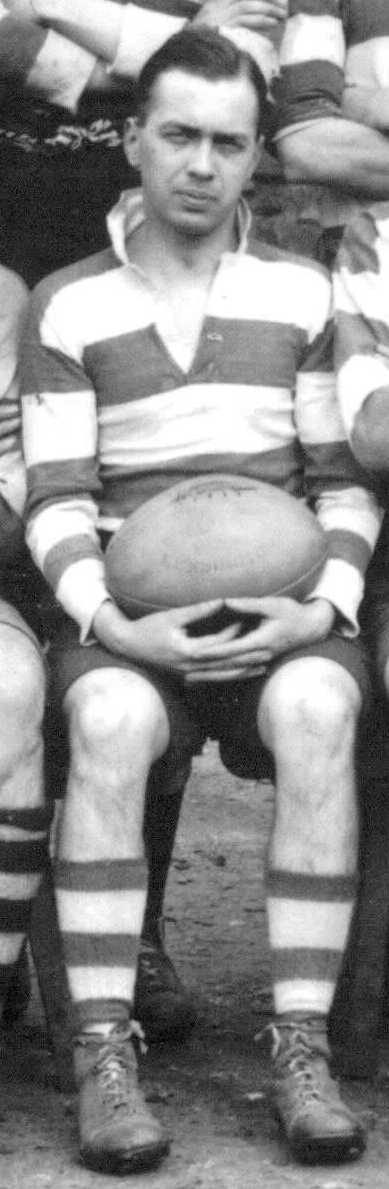

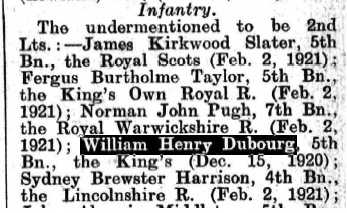

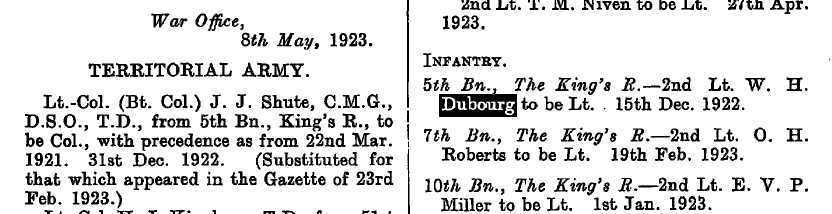

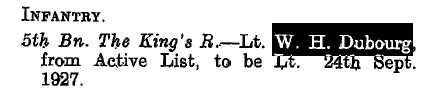

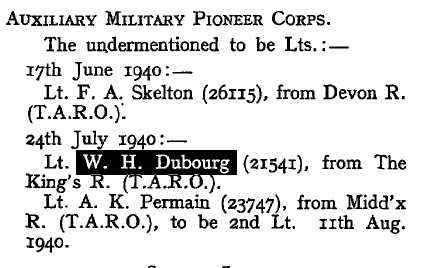

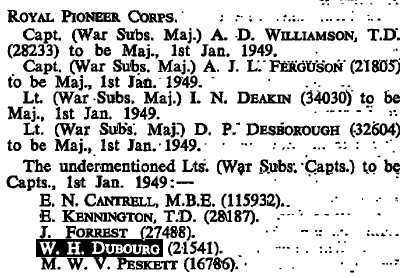

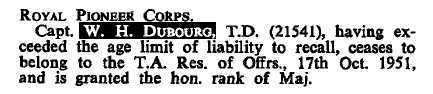

Dr W.H.Dubourg

Played 1922-25

Vice-Presdent Sept 21st 1922

William Henry Dubourg was born 1901 in Liverpool and according to Medical Registers his father William Ernest was a Dental Surgeon, so he probably followed in his footsteps.

Military Service With The Territorials

Around 1950 Captain Dubourg was awarded the Territorial Decoration (T.D.) This is granted for a minimum of 20 years commissioned service, with service in the ranks counting half and war service counting double.

|

|

|

|

|

Liverpool King's Regiment |

Royal Pioneer Corps |

Territorial Decoration |

He passed away in Birkenhead in 1977.

Dr William Henry Dubourg

(1901-1977)

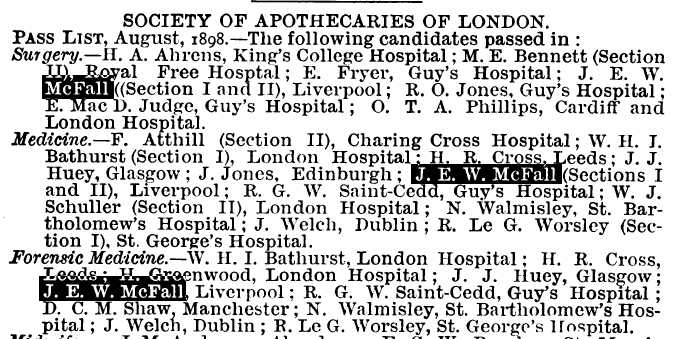

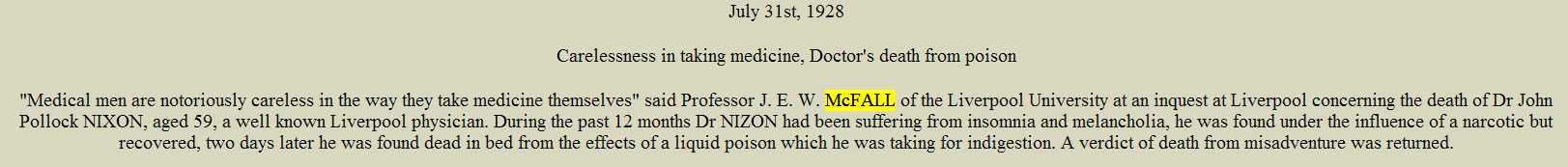

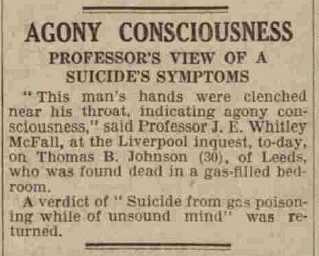

Dr J.E.W.McFall

Elected 17.11.20

Played 1920-21

Vice-President 12.8.21

John Edward Whitley McFall, was born around 1869 in Liverpool. He graduated at Liverpool University in Medicine, Surgery and Forensics in 1898.

He married Florence May Coward in 1900, the same year he opened his GP practice in Green Lane.

The History of Green Lane

Medical Centre

1900 - Medical practice opens at 15 Green Lane owned by Professor McFall who was a forensic doctor as well as a GP.

British

Medical Journal JULY 24, 1909.

UNIVERSITY OF LIVERPOOL.

THE Chancellor, Lord Derby, presided at and Ordinary medical degrees were conferred on the following:

M.D.-J. A.M. Bligh, L. Hutchinson, A. Hendry, H. E. Heapy, H. R. Hturter, T. W. Jones, J. M'Clennan, J. Graham, J. E. W. McFall

During WW1 he rose to the rank of Temp. Major in The Royal Army Medical Corps.

After the war he played at Sefton and became quite involved in the Committee.

20.1.21

Dr McFall, subject to the consent of Mrs McFall, kindly offered to place his dining room at the disposal of the club for a series of lectures on the game by W.J.Smith, but as Mr Milbourn also offered the use of the Smoke Room at the Victoria Café, it was unanimously decided that the latter room was the better of the two, and it was decided to start the instruction there on Tuesday the 20th inst. at 7 p.m.

16.8.21

It was decided to buy a pair of Flesh Gloves for club use. Mr Smith was requested to obtain same, and Dr McFall promised to supply the club with any bandages required.

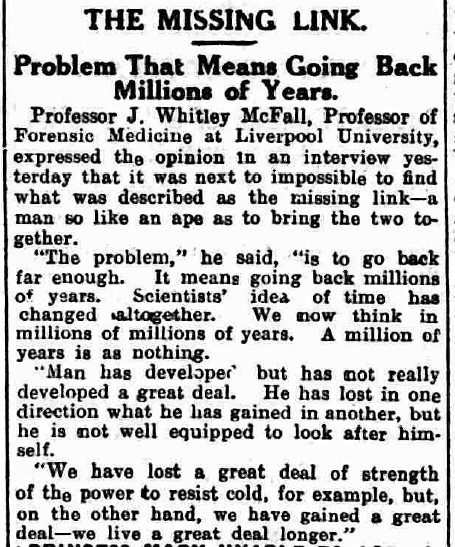

With his position as Professor of Forensic Medicine at Liverpool University he played active roles in many 'murder mysteries.'

|

Reference |

D262/3/1 |

|

Physical Description |

1 photograph |

Those who have been identified by Dr. Vaughan Jones and a colleague are as follows, from left to right in all cases, (those unidentified being indicated by a dash: - ) :-

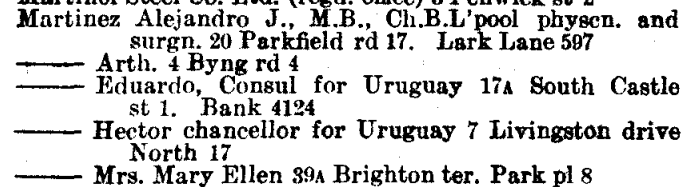

Front row (sitting on carpets and upholstery): A.N. Cameron, T.B. Davie, Langford Williams, Daniel Elihu Davies, Daniel (Hughes)-Davies, D.L. Jones, Trefor Lloyd Hughes, Horace Garner Evans, William Dodd, H.E.C. Sutton, Peter Fox, Miss Lucy Sargeant, Norman Roberts, J.J. Graham, Alun R. Williams, William Poole, John N. Matthews, -, -, Charles Kenneth Holland, ?Hutchinson (probably Hoskinson), ? A.S. Burke, -, -, Alejandro Martinez, T. Lennon, Arthur Lloyd Potter, C. Angior, -, -.

2nd row from front (seated): -, Moroney, Cank, Miss Hall (Librarian), Miss Frances M. Tozer, -, -, Dr. Phoebe Bigland, Dr. J.H. Mather, Dr. Stopford Taylor, Dr. Wadsworth, Dr. Howell Evans, Mr. Hugh Reid, Dr. Thurstan Holland, Professor Beattie, -, Professor J.E.W. McFall, Professor W. Blair Bell, Professor John Hay, Professor R.E. Kelly, Emeritus Professor Rushton Parker, Professor W.J. Dilling, Professor Ernest E. Glynn, Mr. Keith W. Monsarrat, Professor Wood, -, -, Professor Pibble, Dr. R.W. McKenna, Professor Hope, Dr. Balfour Williams, Dr. Duffield, Dr. M. Datnow, -, Dr. Sidney Herd, Dr. E.N. Chamberlain, Dr. R.W. Brookfield, -, Dr. Thompson, Cobban, Galloway.

[www.old-merseytimes.co.uk/deathsandinquests1927to1928.html]

THE ENIGMATIC WALLACE MURDER (1931)

The Murder: On January 19, 1931, a man named Qualtrough tried to put through a call to William Herbert Wallace at his chess club. He had trouble getting the number, and called the operator, a Miss Kelly. She later testified, "It was quite an ordinary voice. It was a man's voice. He said, 'Operator, I have pressed Button A but have not had my correspondent yet.'

I did not have any further conversation with the person in the box. I afterwards connected Anfield 1627 with Bank 3581." Wallace was not at the chess club, and Samuel Beattie, the club manager, took the call. Qualtrough left a message that Wallace should come to his house at 25 Menlove Gardens East the next night at 7:30 P.M.

Who was Qualtrough? When Wallace showed up later at the club, he said that he had never heard of him. But since Wallace was an insurance man, it might have been a business call.

The next night, Wallace went to look for Qualtrough and found that the address, 25 Menlove Gardens East, did not exist. He asked several people for advice, including a constable, but got nowhere. Alarmed, thinking a trick had been played on him, he headed for home.

He tried the key in the front door lock. It wouldn't open, which meant that the door had been bolted from the inside. Surprised, he went and tried the back door to find it locked too. He knocked twice, a signal for his wife, but no one came to the door.

His next-door neighbours, Mr. and Mrs. John Johnston, came out of their house about then, and he asked their advice. Mr. Johnston suggested that Wallace try the Johnston key in the back door. This time, Wallace was able to open the door--without the Johnston key. He went into the house, and the Johnstons saw a light go on upstairs. A minute or so later, he came out and said to them, "Come and see; she has been killed."

Lying on the floor of the little-used sitting room, face down, was Mrs. Wallace. There was a gaping 3" wound in front of her left ear. Underneath her body was a mackintosh--Wallace's mackintosh. Wallace searched the house to see if anything was missing but nothing was. Twice he put his hands to his head and sobbed. "They have finished her," he said. "Look at the brains."

It wasn't long before Constable Williams of the Liverpool City Police arrived. He questioned Wallace and searched the house, finding the main bedroom in some disorder. He found no sign of forcible entry or struggle, no murder weapon. (A charwoman, however, was to say later that an iron bar which was usually kept by the stove was missing.) Wallace, Constable Williams said, was acting in an "extraordinarily cool and calm manner."

Just before 10 P.M., Prof. J. E. W. McFall, a specialist in forensic medicine, arrived. He examined the body and said that death had taken place at 6 o'clock that evening and that she had been hit 11 times, even though the 1st blow probably killed her. He found blood and charring on the mackintosh.

©

1975 - 1981 by

David Wallechinsky & Irving Wallace

Reproduced with permission from "The People's Almanac" series of books.

All rights reserved.

He passed away in Colchester during WW2 in 1941.

Professor J.E.W.McFall M.D.

(1869-1941)

Sefton Doctor Who ?

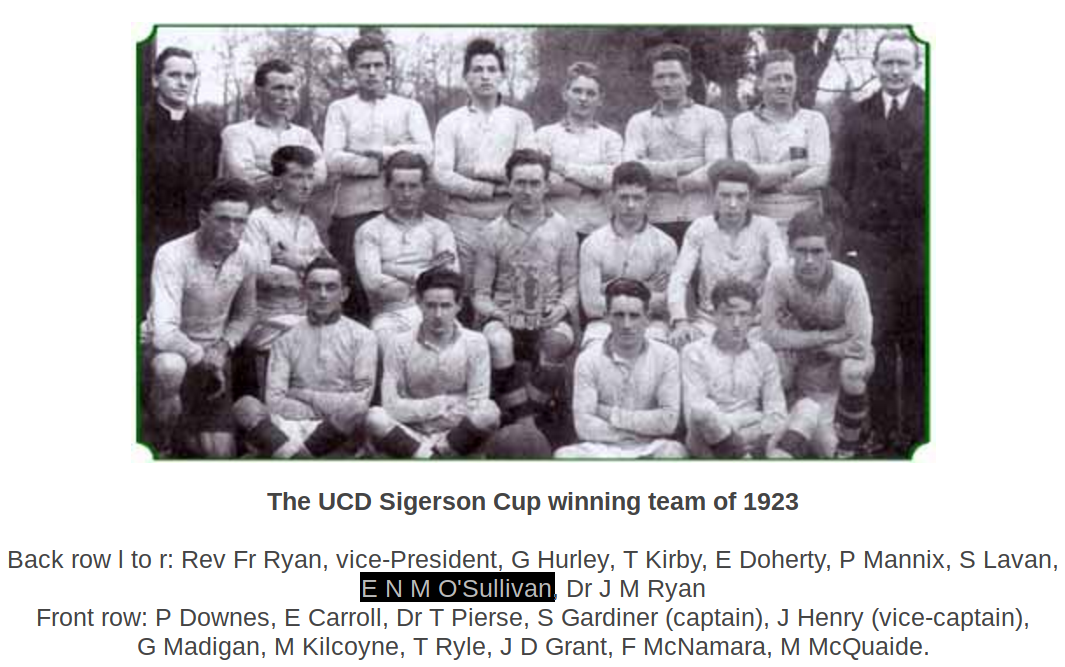

Dr O'Sullivan

Played 1920-21

KEEN GAME AT WEST DERBY.

Bidston beat Sefton A in a hard-fought game on the latter's ground by a goal and two tries (11 points) to a try (3 points). In the first half Sefton were superior in attack and Perrin scored a try. There would have been more scoring but for some resolute tackling by Parry, the Bidston full-back. In the second half, however, Bidston improved, and tries were scored by Galloway, Price, and Woodward, the latter also converting.

The visiting three-quarters were a better lot than Sefton's in that their handling was much superior and their running stronger, while Price and Poe showed a good understanding. Among the forwards Pavillard, A. Taylor and Cooper were prominent. Dr. O'Sullivan, at full-back for Sefton, played a sterling game, and in the second half undoubtedly saved his side from defeat. Bayliss gave his rear division the ball on numerous occasions, only to see it lost through faulty handling. The home forwards were outplayed in the loose, but worked hard, especially Perrin and Ledger. During the scrums the ball was rarely brought out cleanly, a general fault of second-class rugger.

Teams.-Sefton A: Dr. O'Sullivan; Thompson, Millington, Hudson, Davey; Bayliss, M'Gibbon; Ledger, Perrin. Williams, J. A. Cass, Rimmer, Mackenzie, Martinez, Jenkins.

So Who Was He ?

| Dr O'Sullivan |

|

Dr Rumjahn |

seconded

|

J.H.Helme |

Committee Meeting held at Hare and Hounds Hotel November 25th 1921

The resignations of the following were accepted

Dr O'Sullivan (returned to Ireland)A likely candidate may be Dr Éamon O’Sullivan(1896-1966) who was involved with Gaelic football in the 1920's. The Kerryman, known as ‘The Doc’, trained his native county to eight All-Ireland titles over five decades (1924, 1926, 1937, 1946, 1953, 1955, 1959 and 1962).

See the glowing references Dr Eamon O'Sullivan

See youtube clip Dr Eamon O'Sullivan history

Perhaps when the 1921 Census is published more will come to light.

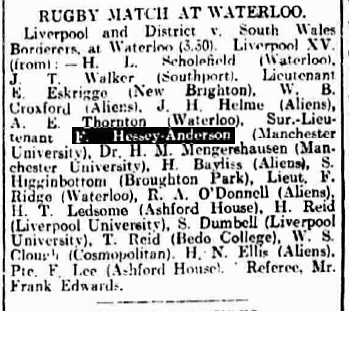

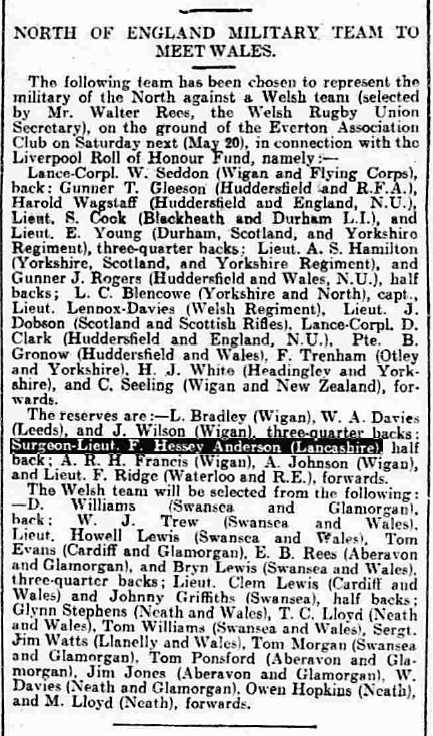

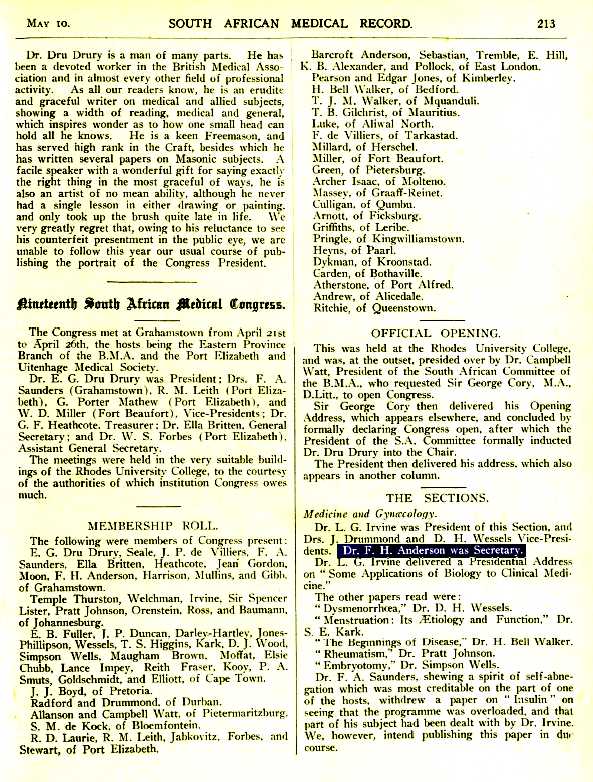

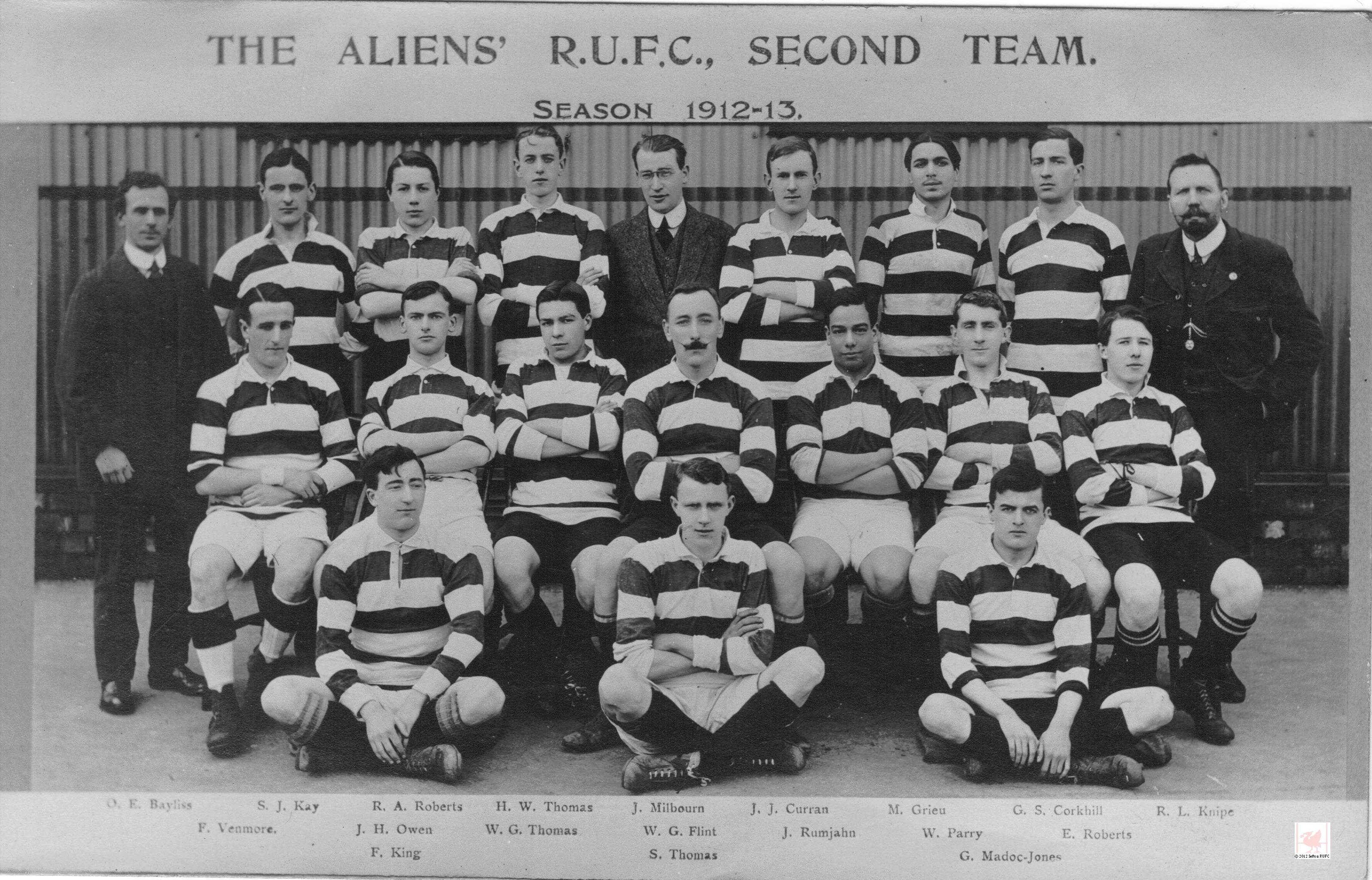

Dr Francis Hessey-Anderson

Played 1913-14

Francis Hessey Anderson was born on the 29th

November 1894, the son of Harry Anderson of Richmond, Natal, South

Africa and attended Hilton College, Natal. He started

his Medical Degree at Manchester University in 1912 where he excelled

in both rugby and cricket, gaining his colours in the 1912-13

season.

In the 1913-14 Winter Sports Supplement of the Manchester University

Magazine he is described as follows “ The most determined of

the

defensive halves: invaluable in saving and tackling, and keen almost to

a fault, Much improved in passing out, and appreciates the value of the

blind side of the scrum. Played for Lancashire throughout the

season”.

There seemed to a close connection between the medical fraternity of

the Aliens and their Manchester colleagues with South African stars

such as Von Mengerhausen and Anderson playing frequent games in the

1913-14 Season.

[Many thanks to Dr James Peters, Archivist at Manchester University Archive & Records Centre]

4th Feb 1913

The Aliens broke the spell

which has remained so long on their

homeland at Clubmoor by a brilliant 25 points to 3 victory. Southport

were weakly represented, their team including eight reserves, Twy being

absent from the pack, and Gifford much missed at half-back. Aliens

opposed them with an exceptionally strong combination, which included Hessey-Anderson,

the Lancashire half-back, and Von Mengershausen, Manchester University

and ex-South Africa three-quarter. Aliens asserted themselves early, as

after three minutes H. Anderson obtained from a five yards' scrum, and

eluding Grimshaw, Wainwright and Mackintosh "docked" safely. Later

Anderson's astuteness enabled Ellis to slip through unmolested. After

dominating the scrum the Aliens heeled out to Anderson, who artfully

enabled the veteran Croston to get in near the posts, Bishop later

cleverly negotiating the major points. Following a line out, Trist also

traversed the Southport lines. Von Mengershausen engineered a bright

venture, and parted to Croxford, who worked the oracle once more.

Aliens thus had 19 points to their credit at the interval.

Olympic resumed with the wind in their favour, and soon managed to

catch their hosts napping. Following a five yards' scrummage Grimshaw

got away with oval to Baldwin, who got home smartly, and thus scored

Southport's solitary try. The homesters, however, continued to

dominate, and further tries came from Anderson and O'Donnell. The

outstanding feature of the game was Anderson's irrepressibility.

Post 4/1/1914

3rd Mar 1914

British Medical Journal 14/2/1914

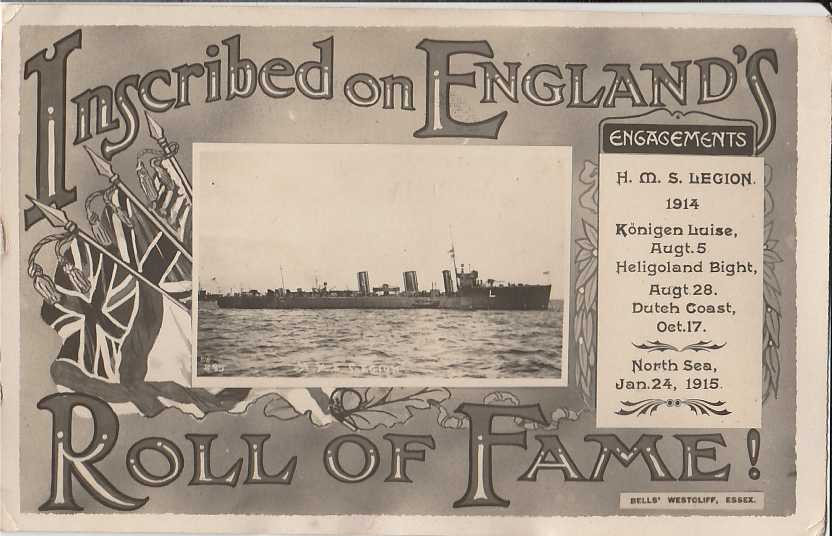

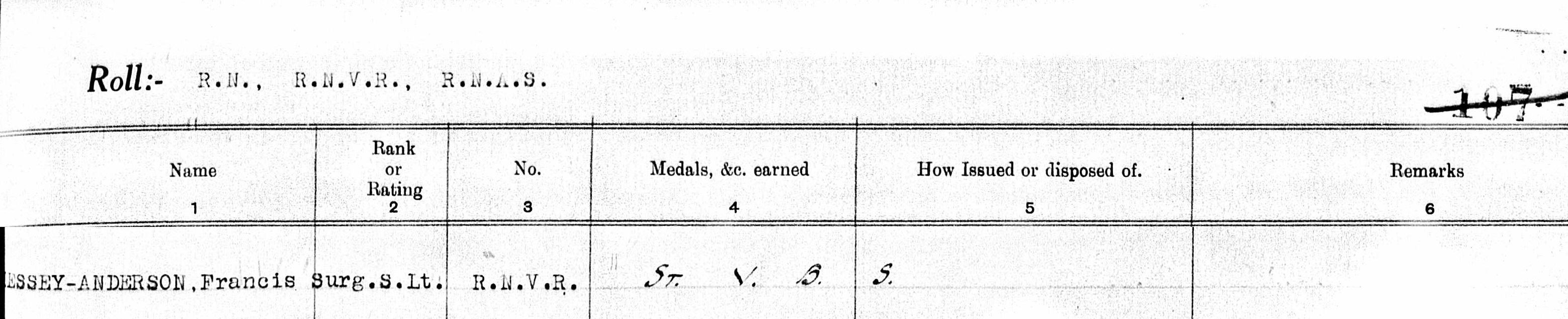

He joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and in June 1915 was appointed Surgeon Probationer(like a GP) aboard the destroyer HMS Legion.

3rd July 1915

Book 1979

[Wikipedia.org]

13th May 1916

[Ancestry.com]

After a break for war service

he graduated with his medical degree

in 1920 and returned to South Africa to continue his career and

sporting prowess.

Dr. F. H. Anderson, ex-captain

of Manchester University and

Lancashire County Rugby XV., has lost very little time in making his

mark in African Rugby football circles. Soon after his return to that

country he led his club, the Wasps Wanderers of Pietermaritzburg, to

victory in final of the Murray Cup; and the Blue Riband of Natal Rugby.

That was on September 24, 1921, the last Saturday of that season.

On May 6 Dr. Anderson played in a Natal trial match for the Rest of

Natal v. Combined Durban. Durban won by 18 points to 12 (thanks to

superior kicking), but so greatly did the Doctor impress that he was

not merely selected to partner W.H.Townsend, the Springbok half-back,

but he was actually, on his first selection for Natal, appointed

captain of the team in succession to H. W. Taylor, the South African

cricket captain, who has now retired from active participation in Rugby

football.

The distinction which has accorded Dr. Anderson will be understood

better when it is explained that the Natal team selected contains no

fewer than five members of the South African side which visited New

Zealand last year and of those five one is a former captain.

The Natal team was due to sail from Durban on May 19 for the purpose of

playing three Currie Cup matches in the Cape Province, their opponents

being the Border, the Eastern Province, and. the Western Province.

To play these three matches the team will have to travel over 2,400

miles, and will be away from Natal 13 days.

Athletic News 1922

According to the South African Medical Journal in 1924 Dr

Anderson had branched into Gyneacology and was Secretary of this

section.

A request to the Secretary of Collegians Rugby Club, Willie J. Field in Pietermarizburg for information on his later life has disappointingly revealed nothing.

Dr F.H.Anderson M.B. Ch.B.

|

|

|

|

|

Military Medal |

The Allied Victory Medal |

British War Medal |

|

|

|

|

R.A.M.C.

Cap Badge

|

South African M.C. Cap Badge |

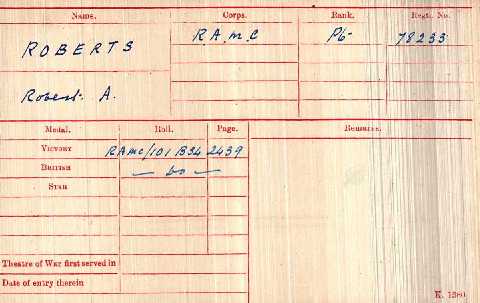

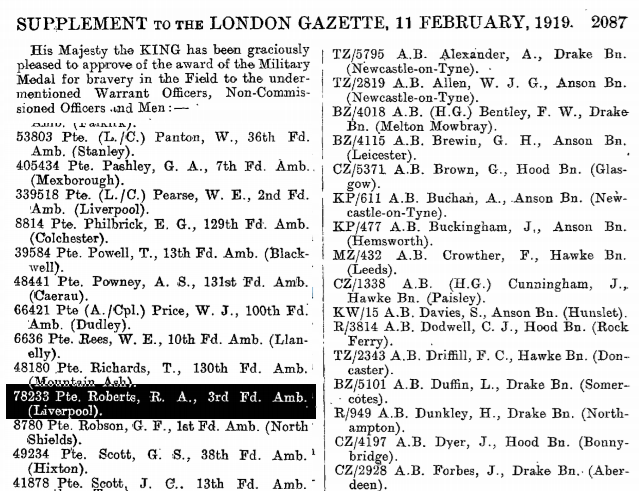

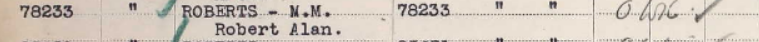

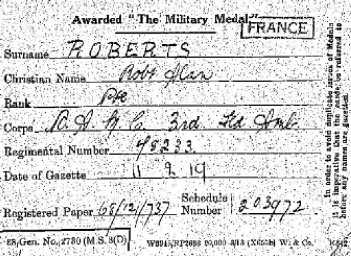

R. A. ROBERTS, M.B., Ch.B., B.Sc., D.M.R.E.

(1894-1961)

Dr Eduardo Martinez Alonso

Written and researched by David Bohl, with the kind help of the Rule family tree and historians world wide.

SEFTON "A" v. WIGAN OLD BOYS "A."

Played at West Derby, ending in a pointless draw.

Teams:- Sefton "A": Kidd, Ovey, Scotson, Morrisey, Fraser, E A. Martinez (captain), G. Martinez, Kay, Darbyshire, Cornick, Simpson, Snape, H. W. Jones, V. Jones, and Price.

Wigan Old Boys 'A': F. Payne, I. Dodson, G.Scott, H. Scott, H. Booth, J. H. Roberts, H.Baxendale, A. H. Crawshaw, W. Lang, A. R. Martland, J. Lea (captain), H. Peacock, H. Leyland, E. Lupton, and A. Goodyear.

The Wiganers were up against a stiff proposition in that their opponents had not lost a match this season. The game was of a gruelling nature, and only the determined tackling of the visitors kept Sefton out. The brothers Martinez were a clever combination and took a lot of stopping. The Old Boys certainly deserved all praise, especially as they had two tries disallowed.

Wigan Examiner 24/10/1922When

Eduardo qualified in Medicine he was uncertain

what his

next step should be, and his

mother, possibly keen to free up a little space in the house where he

lived with his two older and eight younger siblings, suggested that his

grandmother in Madrid would be delighted if he went to stay with her.

In September of 1924 both Eduardo and George resigned from the club.

Taking the huge hint off his mother Dr Martinez set off for Madrid and

took further medical degrees. He was soon in high demand as an English

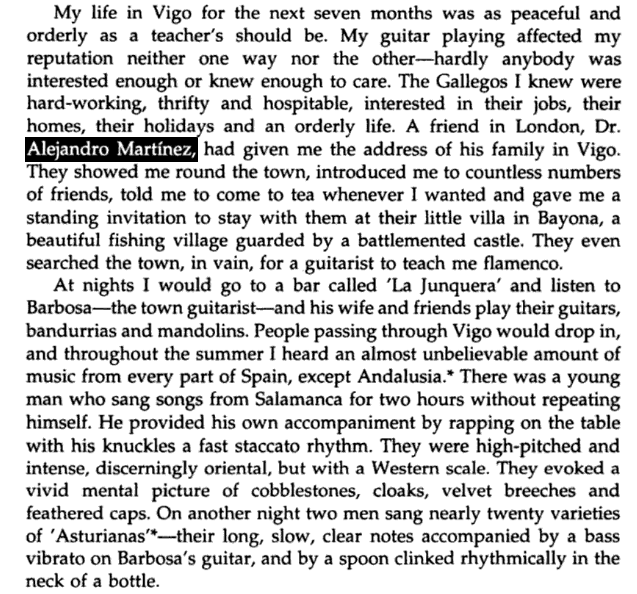

speaking physician, one of his patients

was Queen Ena, the British wife of King Alfonso.

In normal circumstances we could usually finish this life story off with one sentence and say he continued to be a successful thoracic surgeon in Spain, but, he published a book in early 1960's illustrating heroic service to the Allied cause in the Second World War.

'Adventures of a

Doctor' is a very rare

book to find, but luckily a precis has been written recently

by Caroline

Angus Baker

Just in case the link disappears in the future here is the review in

full, our great thanks to Caroline:-

[Adventures of a Doctor

by Eduardo

Martínez Alonso seems to be so rare, I can’t find

any

cover art or a blurb about this book. I managed to purchase a damaged

copy from the New Zealand parliamentary library, and when they tossed

this book to me for a mere $6 (about €3.60), they obviously

didn’t know what a treasure they had. Eduardo

Martínez is

quite an extraordinary man with a story that seems to have been largely

lost. With the market flooded with 1001 Spanish civil war books, it

comes as a great surprise that this book doesn’t get more

recognition.

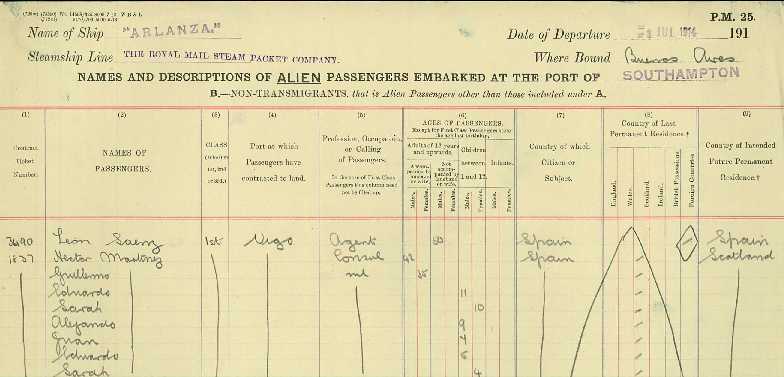

The

story starts

with the author born in Vigo, Galicia in 1903. His father was from

Uruguay, and was the consul in Vigo. As a young boy,

Martínez

travelled to his father’s homeland, along with his family (he

was

one of eleven children, and talks of his mother constantly having to

nurse his siblings). The story tells of life in northern Spain in the

era, and exploits with his brothers and attending a boarding school

with mixed success. In 1912, Martínez’s father

received a

post to Glasgow, and the whole family moved north for a new life.

Martínez dreamed of working in hotels or on ships, able to

meet

people and travel far and wide. He became bilingual at a young age,

seeing the benefit of speaking Spanish, English, French and more. But

it was his father who said he would be a doctor, not a sailor. As each

of the eight boys grew and carved out professions (sisters, of course,

were to be wives and caregivers), the prophecy of the hard-working

consul came true. The family and Martínez recalls the first

world war, his school years and an eventual trip back to Uruguay.

As a

trained

doctor, Martinez moved to Madrid with his grandmother, and speaks of

seeing Anna Pavlova dance at Teatro Real, with the King and Queen in

attendance. He quickly took up a post at Red Cross Hospital, and met

Queen Ena, British wife of King Alfonso XIII, and the Duchess of

Lecera, who were delighted to have an English-speaking doctor. News

travelled of an English-speaking doctor in favour with the queen, and

Martínez was in hot demand. Just eighteen months later,

Martinez

graduated from San Carlos Medical Facility and while meeting the King

and Queen socially and professionally, was appointed the medical

adviser to the royal family. This proved to be an amazing and dangerous

post.

When

the Second

Spanish Republic was founded in 1931, Martínez was in the

palace

in Madrid with the royal family as they were deposed. He tells of

sitting casually with Queen and princesses as the monarchy fell. As the

family were forced into exile and as Spain underwent revolution,

Martínez’s position as a monarchist him an easy

target. As

civil war came five years later, things changed dramatically.

Martínez got his family out of Spain in July 1936, or off to

the

safety of Vigo, and knew he would be in danger as a former royal family

aide. Through his work for the Red Cross, he was ordered by a Communist

faction to work as a doctor for the Republican side of the war.

On

Saturday morning

the shooting started. We sat in a bar and heard the crackling of

machine guns, the burst of hand grenades, and I saw smoke arising from

many quarters of Madrid. By Monday morning a general strike had been

called. Everything was paralysed except murder, arson, and rape. The

Spanish civil war had commenced – Pg 70

Martínez

talks of watching a church burning as priceless works of art were set

alight along with the riches of the churches of Madrid. He saw a priest

thrown on the flames but was unable to save his life when he pulled the

screaming body from the blaze. Most priests were taken out to Casa del

Campo to be shot. Men were burning priests but trying to revive pigeons

which fell from bell towers, overcome by smoke. Martínez had

an

apartment in Madrid, and he hid as many people as he could throughout

the war. Nuns and priest were hidden, and forced to serve meals to men

who sat and spoke of vicious murders they had committed against the

clergy.

Martínez

was

posted to a town outside Badajoz, Cabeza del Buey, in the south-west,

working for the Communists. While running the hospital, a young nurse,

Guadalupe, suggested they flee and work for Franco’s troops

instead, but Martínez seemed convinced that he would be

killed

at some stage, regardless of where he was posted, and claimed no

political alliances. In Cabeza del Buey, he was forced to attend mass

executions of seemingly innocent men, and despair at violent speeches

about revolution and vengeance. He performed many surgeries and saved

lives in the most atrocious conditions. But with no warning,

Martínez was shipped off, with Guadalupe, and sent to

Ocaña, just outside Aranjuez, to work in the prison there,

and

be a prisoner himself. As he had in Cabeza del Buey, Martinez managed

to get some nuns freed from prison to work as nurses, and treated

patients while living in a cell himself. Between dire conditions and

deadly activities, a patient told Martínez that his turn to

be

executed was near. An in understated manner, Martínez talked

of

his prison escape to Valencia in March 1937, were he managed to procure

a fake passport and get aboard the Maine, a ship bound for Marseilles.

Martínez

quickly got himself back in Spain, despite the dangers. He chose to

cross the lines and work for the ‘white’ side of

Spain,

Franco’s rebel army. Red Spain (the Republicans), he felt,

thought nothing of him, his work, and long suspected their cause would

lose the war, one they never had a chance to win. Posted to Burgos,

Valladolid and then San Sebastien, Martínez then found

himself

working on the front lines as Franco’s army continued to

advance

into enemy territory. Towns fell one by one as Martínez

fought

to save lives, but writes in such a humble, unassuming manner. Once in

Zaragoza, Martínez worked hard to care for patients at the

hospitals, and pioneered the use of closed casts on wounds, a procedure

first tried with less success twenty years earlier. Despite the smell

offending wealthy female volunteers, Martínez’s

experiment

helped the lives of many patients otherwise in agony as they recovered.

He was then moved on to his own mobile surgical unit in Teruel in 1938.

Martínez

was

there on the ground when troops stopped in Sarrión, 100kms

north-west of Valencia, as the war finally came to its brutal end. On

April 1st, 1939, the war was over and declared won by Franco in this

small town, and after helping a man and his son to Valencia,

Martínez sought out all those who had helped him during the

war,

and moved back to Madrid. No sooner than Martínez had helped

his

friends and former nurses, and begged for clemency for some condemned

to death by the new regime, the second world war broke out. With some

family in Vigo and some Britain, travelling on multiple passports,

danger was again faced. As Hitler plowed through Europe, Madrid

suffered greatly after the civil war and Martínez went to

work

at Miranda de Ebro, near Burgos, to help war refugees from all nations.

With such a humble attitude, he glossed over his feat to aid refugees

out of Spain, saving their lives, until in 1942, when his ferrying of

innocents was discovered and he was forced to flee Spain. His time

working with British Naval Attaché, Captain Alan Hillgarth

is

barely touched upon, but should surely serve as an incredible tale of a

man saving lives at great risk to his own. This two-year period alone

could serve as a story all of its own. Just his dramatic escape would

serve as its own story, but the author covers it in a few sentences,

and neglects to mention he fled with a new wife. He also failed to

mention his first marriage which produced two children, but was

annulled after Franco took power in 1939 (His wife was a British woman

who went home without him). I only found about either marriage after

studying the doctor further myself. There are no clues to whom these

women are at any point in the book. His personal life is never touched

upon.

Again,

Martínez talks little of his involvement with the rest of

the

world war, after being detained when first arriving in Britain (no idea

if his Spanish wife was also detained), but worked as a spy for Britain

throughout and barely talks about it. He worked at Queen Mary Hospital

after the war and oversaw great new procedural advances, meeting some

of Europe’s finest surgeons, but then returned home to

Madrid.

Life was hard in the beleaguered nation, and he again went to work at

Red Cross Hospital, specialising in chest surgery. He then moved on to

working as the doctor for the Castellana Hilton, newly opened in 1953.

He recounts stories of wealthy Americans, and famous movies stars

(unnamed) alike, who came to Madrid for all sorts of reasons. He spoke

with frustration at his patients demanding penicillin shots, not

wanting to discuss why they need this medication. Many guests, male and

female, had a penchant for sleeping around and wanting medicine to

atone their sins, either before or just after the liaisons which bore

infections. One guest talks of being raped and demanding penicillin,

though the story is far from convincing to the doctor. Sexual

liberation had come to the foreign guests at the Hilton, and expected

Martínez’s penicillin to cover it up. He makes his

disdain

clear for these patients and the abuse of this groundbreaking

medication, and of the myriad of alcoholics he was forced to attend to,

when little could really be done for them.

The

book is written

in the manner of a doctor – no-nonsense, no fussing with

detail,

just the raw facts given out without prejudice. Martínez is

a

man with the story worthy of a Hollywood blockbuster, but it

wouldn’t be his style. This book was written in 1961, and

Martinez lived until 1972. It shows what really stood out to the doctor

in his life, because details are excluded, and there are many secret

operations he simply never wanted to discuss. He is free and easy with

dates – because I know the civil war, I could piece together

the

timelines of the book, but needed to look up world war details and the

opening of the Madrid Hilton, just to give myself an idea of how much

time passed between chapters.

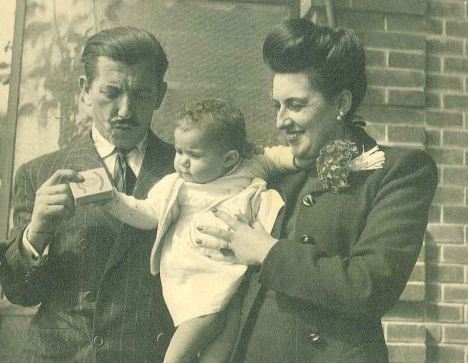

*above photo taken just prior to release from the Spanish army, 1939.

Photo supplied in the book (page 112)]

So it looks like we have a real life Spanish episode of "Hola, Hola" on our hands, but the lid really came off events in 2005 when a Special Operations Executive file held at the National Archives in Kew was de-classified.

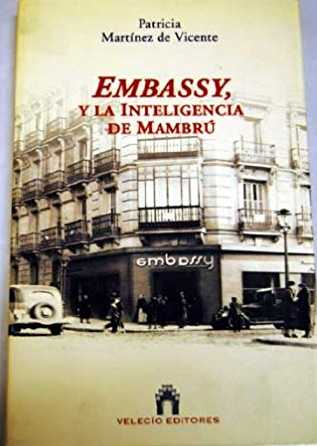

Martinez’s daughter, Patricia Martínez De Vicente became aware of this and after a lengthy trawl through all this unknown fascinating information she wrote a book called "The Enclave, Embassy".

Another

online article by Nicholas Coni

combines 'Adventures of a

Doctor' and 'La Clave, Embassy' entitled Surgeon

Who Undertook Special Operations

Once again just in case the link disappears in the future here is the

page in full, our great thanks to Nicholas:-

References

1. Martínez Alonso E. Adventures of a Doctor.

London:

Robert Hale, 1962

2. Martínez de Vicente P. Embassy y la

Inteligencia de

Mambrú. Madrid: Velecío, 2003

3. Martínez de Vicente P. Personal Communication,

2009

4. Knoblaugh HE. Correspondent in Spain. London:

Sheen and

Ward, 1937: 85-88

5. Martínez Alonso E. Correspondence 1938: Archive

WA/HMM/CO/Alp/15: Box 69,

Wellcome

Library

6. Thomas H. The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin, (1961)

3rd

edn. 1977: 940

7. Preston P. Franco. London: HarperCollins (1993) Fontana

edn.

1995: 393-400

8. Ibid: 347, 957

9. Smyth D. Diplomacy and Strategy of Survival: British Policy and

Franco’s Spain

1940-

41,Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986: 26

10. Payne S.G Franco and Hitler, New Haven: Yale University Press,

2008: 69

11. Smyth D. Op. cit: 28

12. Smyth D. Hillgarth, Alan Hugh (1899-1978), rev. Oxford Dictionary

of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004; online

edition, January 2008

<http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/31233> accessed 9

March

2009

13. Avni H. Spain, the Jews, and Franco, trans. Martíneznuel

Shimoni, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1982:

72-79

14. Ibid: 180

15. Ibid: 91

16. Hoare S.J.G. Ambassador on Special Mission, London: Collins, 1946:

226-238

17. Records of Special Operations Executive, National Archives, Kew,

file HS 9/26/5

18. Alvárez-Sierra J. (ed.) Diccionario de Autoridades

Médicas, Madrid: Editora Nacional, 1963: 317

19 Macintosh R.R. Correspondence 1946: Archive 1946 PP/RRM/C/11,

Wellcome Library, London

20. Book Reviews Lancet 1962; I: 1106

Footnotes

a. Another term used in this context was

“outfiltration”

(although medical readers would undoubtedly favour

“exfiltration”).

b. Urgencias Torácicas, Madrid:

Gráficas Udina, 1959

Legend

to Figure

Figure 1. Eduardo Martínez Alonso in the uniform of a

Capitán Médico in the Nationalist Army]

Once again The Aliens have come up trumps, our own Oskar Schindler

|

|

|

King

George Medal for Courage

in

the Cause of Freedom

|

Polish

Gold Cross of Merit

|

Dr

Eduardo Martinez Alonso

(1903-1972)

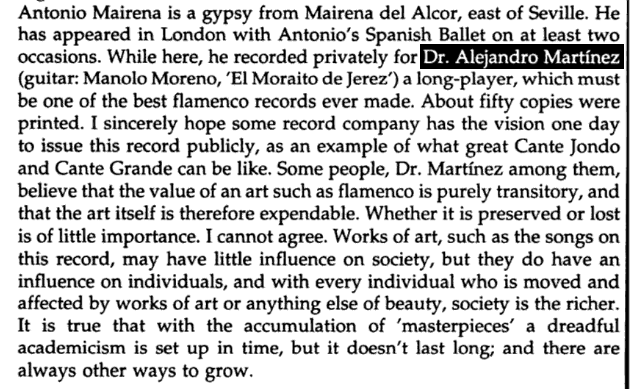

Dr

Alejandro Jaun Martinez

(1909-1978)

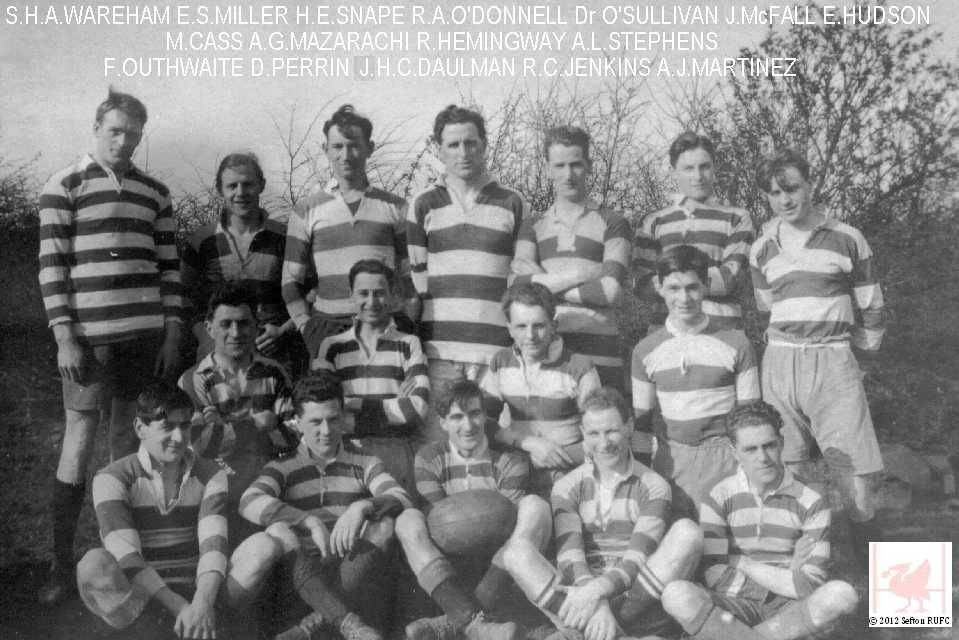

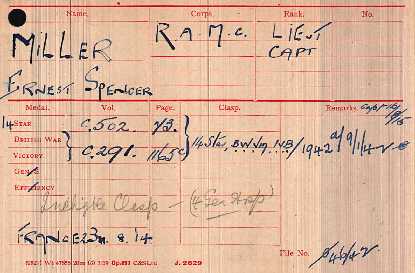

Ernest Spencer Miller was born in Liverpool, 1886 where his father was a Solicitor in Princes Park. He lived in an impressive end terrace on Peel St with his two brothers and two sisters, not forgetting the all important house servant.

Played 1920-21

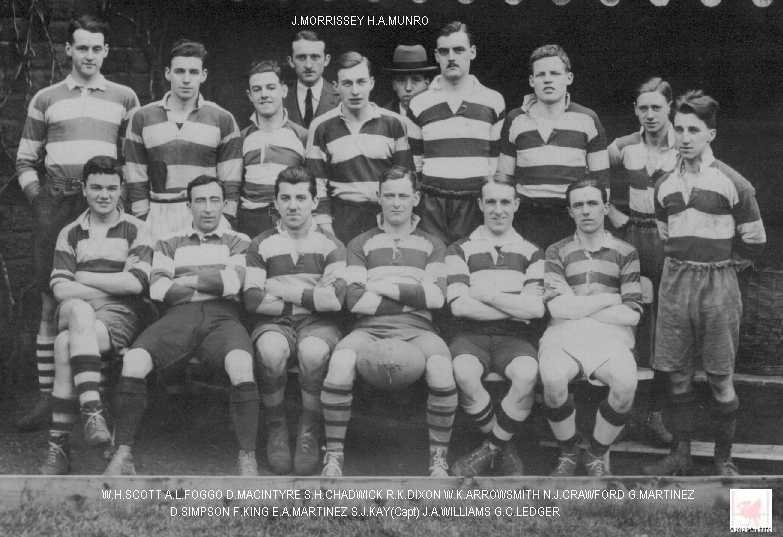

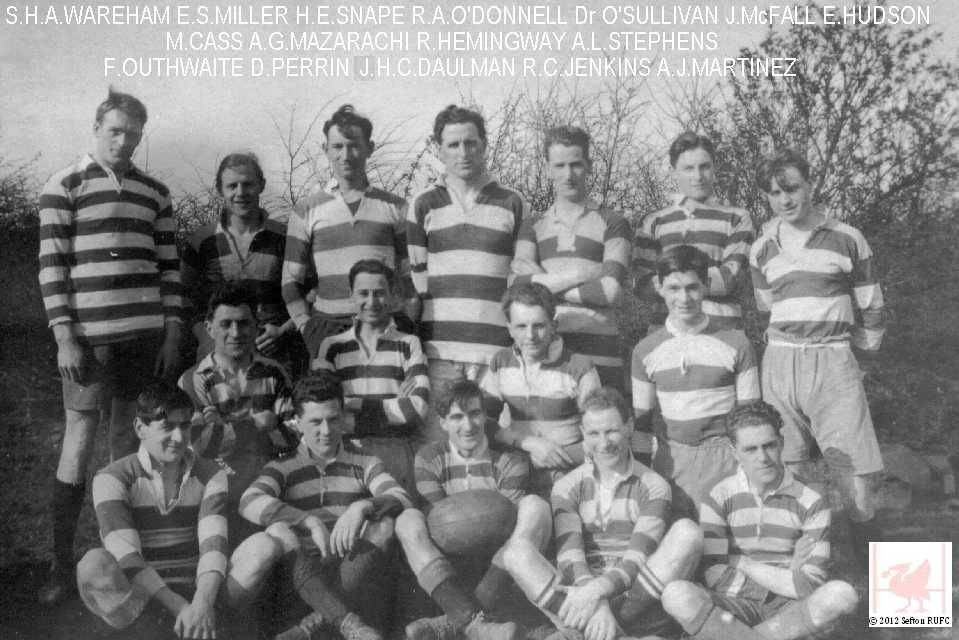

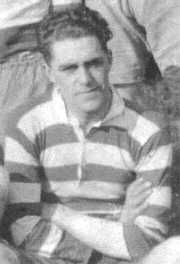

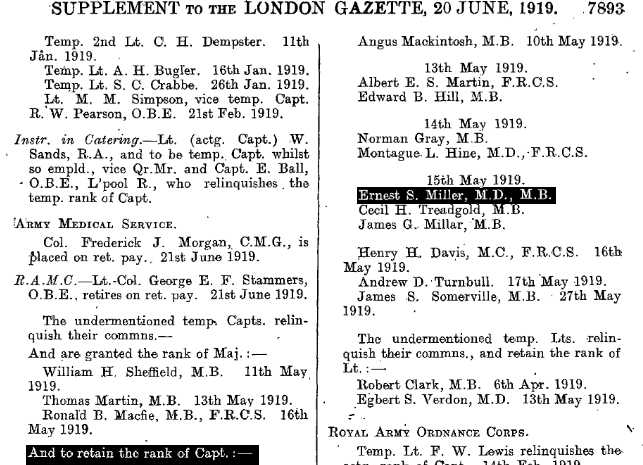

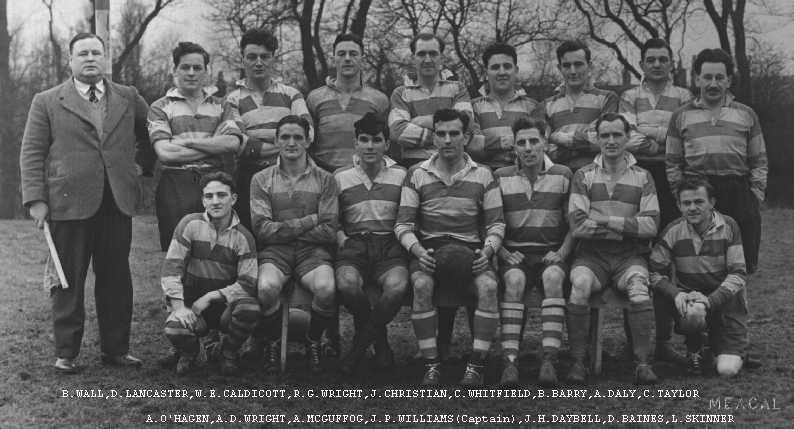

Back Row S.H.A.WAREHAM Dr E.S.MILLER H.E.SNAPE R.A.O'DONNELL Dr O'SULLIVAN Dr J.McFALL E.HUDSON

Middle Row M.CASS A.G.MAZARACHI R.HEMINGWAY A.L.STEPHENS

Front Row F.OUTHWAITE D.PERRIN H.C.F.DAULMAN R.C.JENKINS Dr A.J.MARTINEZ

SEFTON FAIL AT SOUTHPORT.

For the major portion of the game at Victoria Park, where Sefton were the visitors, there was only one team in it. In the first half Sefton were rarely out of their own territory. This was not so much the result of Southport's play as of the inefficiency of Sefton. Scott was the first to get over, but the goal-kick was from an extremely difficult angle, and J. Twynne was not to be blamed for failing. Before the interval, Scott and Guest scored between the posts, and Gifford easily added the extra points. Sefton did better in the second half, Bellamy grounding the ball behind the uprights. Miller, however, placed wide. Irving put Southport further ahead with a drop goal, but Gifford and Twynne failed from tries by Walker and Buck. In all departments Southport were the cleverer side. Result: Southport, 23; Sefton 3.

Daily Post 13/12/1920

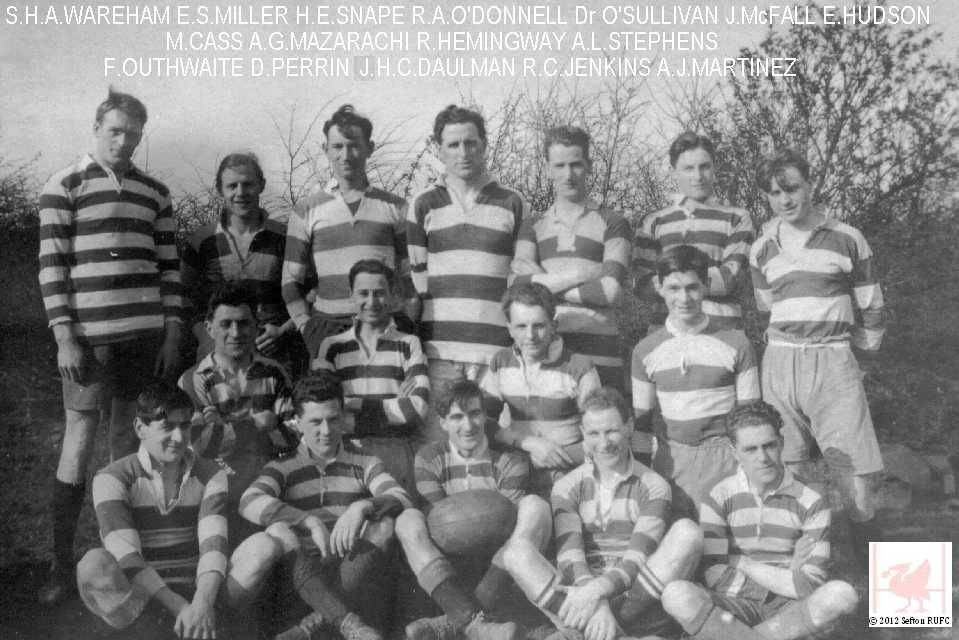

In 1921 he was made President of the Royal Naval Recruiting Headquarters.

Throughout the inter-war years his career progressed admirably:-

It would seem Dr Miller was quite a religious person and there are reports of him being a Quaker. This might explain his 1907 passenger record of a trip to Philadelphia where there is a large Quaker congregation.

Dr Miller passed away in Aughton, Lancashire in 1976

|

|

|

1914

Star, British War and Victory Medals

|

R.A.M.C. Cap Badge |

Dr Ernest Spencer Miller M.D Ch.B M.B D.L.O

(1886-1976)

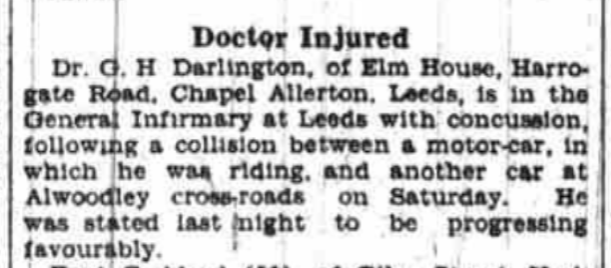

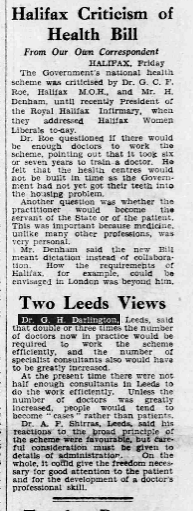

Dr G.H.Darlington

Returning to civilian life in Liverpool GHD continued in his chosen speciality and was Clinical Assistant and House Surgeon at the Venereal Department in the Royal Infirmary.

A

total change in career

arrived with a new opportunity in Leeds when he became Medical Officer

at Shadwell School for Boys, one of the "Industrial" type

establishments for wayward kids. A number of Aliens also took up

teaching posts within Industrial Schools - J.D.Johnstone,

W.J.Trist, R.A.O'Donnell

and J.S.Lloyd.

Shadwell

School,

despite its austere regime excelled in athletics, swimming, gymnastics

and boxing in inter-school and inter-county competitions.

By the 1930's GHD had joined a Medical Practice in Chapel Allerton, "Darlington and Carr" was his last known position.

Critical of the number of GP's in practice -1946.

|

|

|

|

1915

Star, British War and Victory Medals

|

Reverse

of his

1915 Star

|

R.A.M.C. Cap Badge |

George passed away in Chapel Allerton, Leeds 1956

Dr George

Hellyar

Darlington M.B Ch.B D.P.H

(1892-1956)

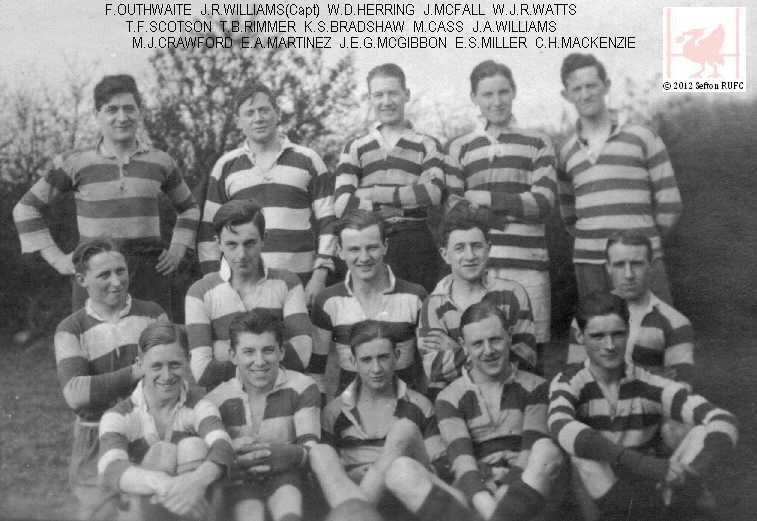

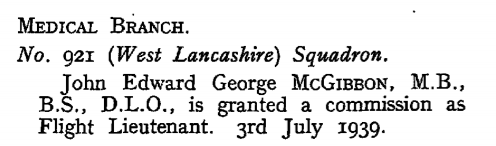

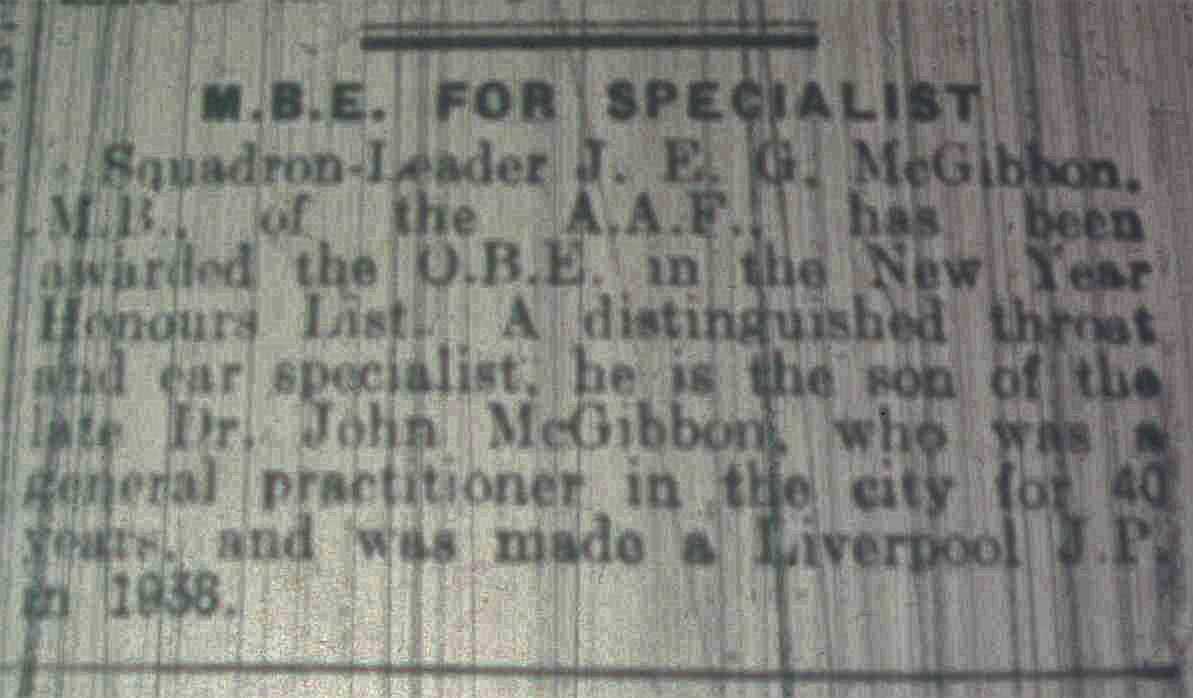

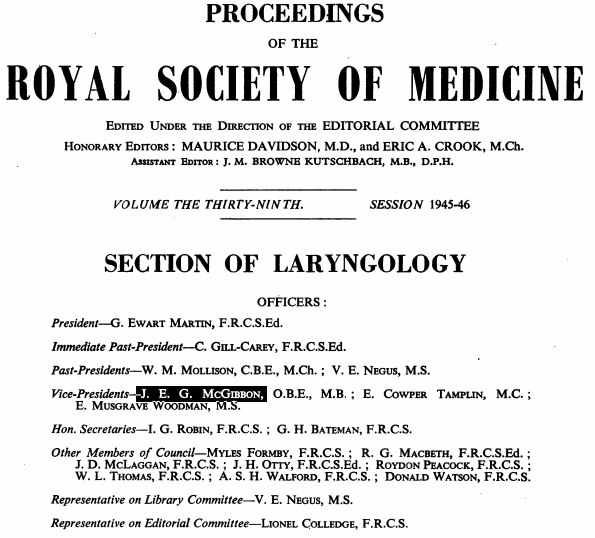

Dr J.E.G.McGibbon

Played 1920-21

After WW2 he was made a vice-president of the British Medical Association and had many professional activities with the United Liverpool Hospitals.

After his retirement he was pleased to be made honorary consultant and jointly made a comprehensive textbook on diagnostic bronchoscopy. In due time he succeeded in lectureship in the department of laryngology at Liverpool University and as a teacher of nurses in the Royal Southern hospital., his kindness to the younger trainees was much appreciated.

|

|

|

WW1

British War and Victory Medals

|

Order

of the British Empire

|

It did not surprise his colleagues that Dr McGibbon had died within a few hours of his last work on October 25th 1959

Dr John

Edward George McGibbon OBE M.B B.S D.L.O

(1893-1959)

Dr Cyril Taylor-a life of commitment

By Gideon Ben-Tovim

There are some people with so much energy, so much vitality, with such strength of personality that it is almost impossible to think that they are no longer with us-nor is it possible to do justice to their lives in a few words.

Cyril Taylor was such a person, a man of extraordinary drive, a medical visionary , a life-long socialist ,a unique individual with enormous charm, warmth and commitment. He was one of this city's finest citizens, making a profound mark on the lives of many .

Cyril was born 79 years ago in New Brighton to orthodox Jewish parents, and was brought up with his sister Doreen (who now lives in Australia) in Wallasey where the family lived over his father's shop near the Town Hall .His grandparents fled the pogroms of Eastern Europe to settle on Merseyside , the family name changing from Zadesky to Taylor in line with the profession of Cyril's father, who eventually moved into the wireless business after become bankrupt through the rise of the Montague Burton off the peg suits.

Some of you will know Cyril's grand-father's house in Falkner Square, the beautiful white mansion on the corner of Catharine St where Cyril would recount sliding along the polished hallway floors or attending the more sombre reading of his grand-father's will.

Cyril became active in the Jewish youth movement, attending Zionist habonim camps, but he moved away from Zionism and towards the international socialism of the Communist movement in his late teen age years, which were in the heavily political 1930s with the real threat of fascism over-shadowing Europe.

Hearing a talk on the Spanish civil war as a sixth-former at Wallasey Grammar was an important influence in Cyril's political development.

He trained as a medical student at Liverpool University during the war years, graduating in 1943.He recounted that as a student he was sent to Durning Rd where an air-raid shelter had received a direct hit, to try and give medical aid.

He was based at Alder Hey hospital, which had been transformed into a medical receiving centre and treated some of the war wounded returning from Dunkirk.

He gained a reputation for eating his sandwiches during dissection demonstrations and kept a pickled leg under his bed, showing an early interest in orthopaedics!

It was at this time that he developed his great belief in the necessity of a national health service, free at the point of need.

Later he was to be part of a delegation of socialist doctors who lobbied Nye Bevan, urging him not to give way to the doctors who would later, proverbially, have their "mouths stuffed with gold".

Cyril's involvement in the Communist Party was for him an influence of the utmost importance ,and he remained an active and committed member from his student days at University until he left the Communist Party in disillusionment, as did so many after the events of1956. His letter of resignation was to him a most significant document, which he shared with Marge and myself many years later.

He joined the Labour Party, of which he remained an active member up to the end, serving as a Councillor for the Granby Ward from 1965 to 1980,including a major term as Chair of Social Services. He was an extremely dedicated and effective Chair, developing a number of new initiatives to support the poorer and more disadvantaged members of the community.

He was a pioneer of joined up thinking, arguing for housing, social services and health to be considered together, encouraging the early growth of housing associations, fighting tirelessly and often successfully against slum landlords at rent tribunals to bring down his constituents' rent levels .

He established the Liverpool Association for the Disabled, and made sure that elderly people had free access to telephone lines. He knew that the ill-health he witnessed every day was fundamentally related to poverty, and that inequality had to be fought in every sphere of life.

As he himself wrote," Both as a medical student and later as a doctor ,it had always seemed entirely appropriate for me to be part of the broad political struggle to change the unequal society for one in which every citizen would have an equal opportunity for education, for the development of their talents and the right to work for their own benefit and that of society".

As well as a tireless political campaigner, Cyril was a rounded human being with a rich personal ,social and cultural life.

After the war, he served as a Major in the army ,including a period in charge of the British Hospital in Khartoum. On his return, he was politically victimised in several jobs, including being sacked by the Liverpool Shipping Federation.

So he then decided to set up his own practice, which he did in Sefton Drive, calling on all his political comrades and allies to join his list so that he could bring in some income.

Sefton Drive , Cyril's home for many years with his wife Pat and his children Jeff and Susie, was not only a power-house of the political left, where many a resolution was crafted, many a meeting fixed, and many an important medical, social or political project hatched.

It was also a house full of people , friends and relatives , and generally an open house for many a person in need-Cyril and Pat were amongst the first to welcome Chilean refugees into their home after the brutal military coup of 1973.

The house was a cultural centre too, the Unity Theatre( whose leading lady Norah Rushton is with us today ) storing their costumes ,props and scenery in the basement, and using the garden for their rehearsals.

It was a house full of Cyril's jokes and banter , including the cancerous pickled lung kept on the dinner table to try to ensure that Geoff and Susie didn't take up smoking cigarettes.

And of course it was the surgery-the most unique surgery imaginable, with political magazines to read whilst waiting, political posters and cartoons on the wall to look at, and the tingling anticipation of an encounter with Cyril: one quick look of his penetrating gaze and he could see there was nothing life-threatening to worry about.

Then he'd say "well there's nothing I can do of course that will make any difference, but I suppose you want me to give you something"…he'd scribble out the prescription, and get on to the real business-the political conversation .

Of course "conversation" is perhaps an exaggeration- it was more that Cyril would hold forth in his inimitable manner about the current issues of the day ,the latest iniquities of the Conservative Government or the international news , add a bit of outrageous local political gossip, tell a joke or three, until the dreaded "right-ee-ho" came and the ten minutes of magic were at an end.

There was also the sport-Cyril had been a great Rugby player in his youth,playing for Liverpool University as a prop in the front row and he continued to play for Sefton Rugby Club until he was 40.

And then there was the tennis, where he would declare that he had a line with the almighty who always made sure that the weather was benign-at least most of the time.

In the final phase of his life, Cyril entered a new relationship with Sylvia, and together they played a very active role in health politics. During this period Cyril served as the President of the Socialist Medical Health Association, continuing his life-long campaign both for a quality national health service,and for social policies that linked inequalities to health. Earlier this year he was awarded the prestigious Duncan medal in recognition of his lifetime work in the field of primary health care.

After retiring not long after 65,something he advocated as part of his anti-elitist views that doctors should be treated like the rest of society, he of course could not resist doing locums for as long as his health allowed it. From 1988 when he set up home with Sylvia in Wavertree until July 1999 when he decided to hang up his stethoscope, he continued doing regular locums in 25 different surgeries in Liverpool and the Wirral.

He enthusiastically supported Sylvia in her activities at Greenham Common and her involvement in Womens Aid for Peace, where he ensured that medical supplies were made available to take out to the former Yugoslavia.

He maintained an active involvement in the Labour Party, which he continued to do after moving with Sylvia to West Kirby two years ago where they quickly set about helping to sort out the Constituency Party.

One of the pleasures of his final years was reconnecting with his many cousins, attending many Friday evening meals that became known as "the "cousinings."

His life had ,in a sense, turned full circle ."I'm Cyril from the Wirral" he would joke, and in fact he derived great pleasure from striding around the West Kirby Marina in all weathers, and in finding many pleasurable walks.

In our final conversation, Cyril told me of a walk where he had retraced his boyhood journeys ,including from his home to his school; he even mentioned he had looked for the house where my own father had been a GP in Wallasey.

As well as the importance to him of his relationship to his children , Cyril gained great enjoyment from his first grand-child, and also from Sylvia's children and grand-children.

We will all have our own memories of Cyril. He is an indelible part of all our lives, and Sylvia would like you to think that some of the 79 red roses that represent the years of Cyril's life also signify special memories of your own relationship with this extraordinary man.

His life of commitment and vision has been an inspiration and a joy to us all. He has made an enormous contribution to the city, to the health,the life-chances and the hopes particularly of the more disadvantaged sections of the community .We will truly not see his like again.

20.12.2000